The Rise and Fall of Minnesota's Independence Party

How the once potent threat to the state two-party system completely fell off the political radar

Ever since I started analyzing Minnesota politics, one of the earliest things that stood out to me is that in comparison to many other states, Minnesota had one of the highest tendencies to elect outsiders who had never held elected office. Whether it be comedians, businessmen, or college professors, we have had a sizable chunk of elected officials who fall under this classification.

But Minnesota’s outsider streak isn’t just limited to who it chooses to elect for public office within the two-party framework. It also extends to the overperformance of third-party efforts. This fact in particular has had a massive historical impact on the politics of Minnesota. The most notable of these was the Farmer-Labor Party, a left-wing populist party that grew to dominate statewide politics throughout the late 1920s and 1930s. It became so much of a force that as the party was dying down, it entered into a merger agreement with the third-place state Democratic Party, leading to the creation of the DFL, which still stands as the official statewide Democratic Party affiliate to this very day. Beyond this, there are other notable third-party efforts in both the distant past and present, from the 19th-century agrarian Alliance Party to the 21st-century vote-splitting pro-Marijuana parties. For a large chunk of Minnesota’s political history, third parties have played a massive role, and it’s likely that one will do so again at some point in the future.

But of all the third-party efforts Minnesota has had so far, there is one that stands out as particularly interesting to me. At one point, it stood as a potential shakeup to a political game many had begun to assume was growing stagnant. Seemingly overnight, it looked like it had just turned the entire system upside down, representing the beginning of the end of the two-party system. That was the Independence Party of Minnesota, one of the more recent and most significant third-party efforts in state history.

If you have only started paying attention to statewide politics recently, you probably have no idea who these guys are. While they technically still exist, you could be entirely forgiven for throwing them in the same box as other lackluster third-party efforts. In the few races they even bother to still contest, they struggle to even get above 1% of the vote, consistently falling well behind not just the two major parties, but even the various other failed third-party efforts that run alongside them. There isn’t a single member of the party that holds any amount of name recognition. Even the party website cannot be asked to give their top leadership non-archived pages of their own.

For most third parties, none of this is shocking or surprising. Given our current first-past-the-post and electoral college system, the opportunity for any third party to make a real mark on any election is incredibly difficult. Much to the disappointment of many Americans who want a real third party, the way our current system is made naturally skews in favor of creating a two-party system. That’s why they almost never get off the ground: our current system just doesn’t make it especially feasible.

That being said, there are still some third parties that have managed to overcome this massive barrier and actually have a degree of major influence over politics in their own right. The Independence Party was one of these parties.

At one point, the Independence Party looked like it was on top of the world. First created in 1992, it very quickly began to emerge as a real power player in every election cycle throughout the rest of the 1990s. It all came together for them in the 1998 elections, which saw the party shock the world and win control of the Governor’s Mansion, beating back both of the major parties in the process. In a midterm election year mostly only known today as an unremarkable status quo affair, this shock result in the North Star State stood out more so than any other result in the country. In just one night, the Independence Party became the talk of the town, a potential sign that fundamental change was on the horizon for politics in the state. It’s something that most third parties only dream of having the opportunity to show off. That’s what makes the Independence Party stand out in comparison to the rest: it was actually a force of real political influence, and by extension, saw itself have a dramatic fall from grace that the Greens or Libertarians haven’t had yet.

In this article, I want to go over how all of it came to be, why exactly it was so appealing to Minnesotans, and analyze how all of it slowly began to fall apart, becoming little more than a distant memory for Gen X Minnesotans who moved to the Twin Cities suburbs in the 1990s. In order to do that, let’s start by taking a look at what was occurring in national politics.

The Foundation

As I mentioned previously, one of the most commonly known things about United States politics is that it is a defacto two-party system, with the Democratic and Republican parties being the only two realistically capable of holding a significant amount of power. Thanks to how elections are run, there just isn’t really an opportunity for third parties to get off the ground. More often than not, their only real role in elections is serving as a potential spoiler to one of the two major parties, a role that basically ensures that they will never get real support in any election. It’s a massive hill to climb, and for the vast majority of third-party runs, it’s one they never even get close to conquering.

But that being said, there are still some efforts free of the two-party system that do manage to have real influence. For one reason or another, they can get beyond the fears of being a vote splitter and actually manage to create a real, above-single-digit level of support for themselves. It doesn’t happen too often, but when it does, it tends to spawn a movement alongside it, one that almost always shapes the way politics is done for years to come.

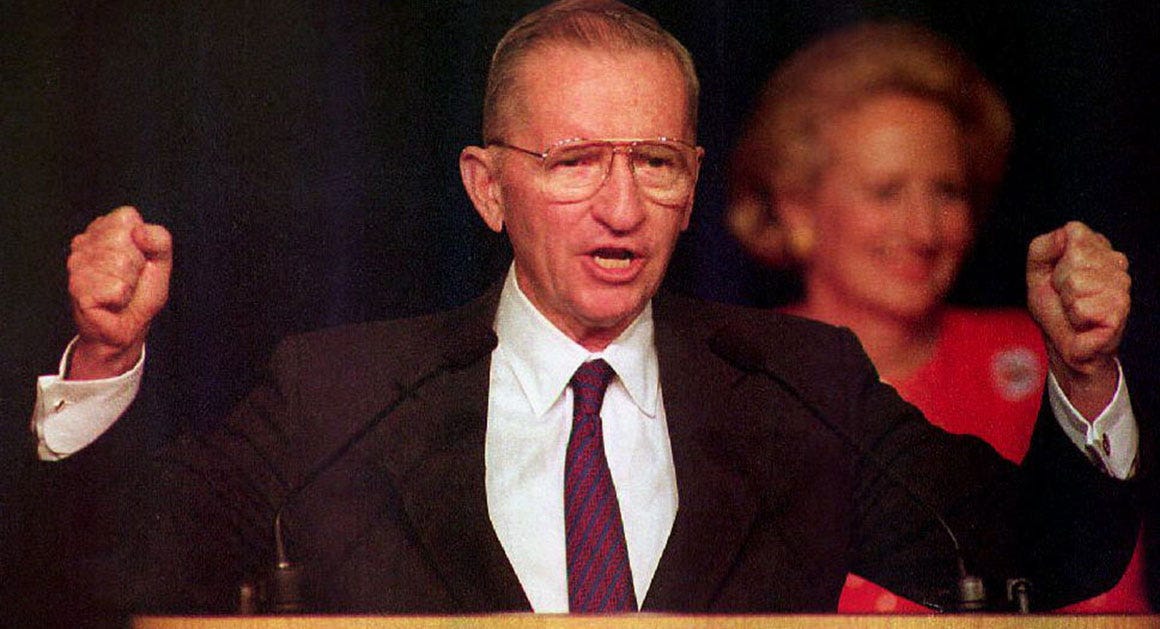

On the national stage, despite the electoral college system making it virtually impossible for them to win, there are a decent amount of times in history when this kind of movement has been spawned. Whether it be James Weaver’s Populist Party in 1892, Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party in 1912, or George Wallace’s American Independent run in 1968, there are quite a few examples of influential third-party or independent runs that actually somewhat managed to get off the ground. However, the most recent and one of the most interesting ones came in the early 1990s, the independent run by businessman Ross Perot.

This is where the story begins for our friends at the Independence Party. Inspired by his populist, independent, and outsider message, supporters of the Texan businessman’s campaign founded the party in 1992, fielding one of their top leaders, the president of Dayton Furniture Dean Barkley to run in Minnesota’s 6th congressional district as a test run. This later made it part of a two-way strategy for Perot supporters, who would also form a statewide branch of United We Stand America (UWSA) to help organize on behalf of the Perot movement. This went beyond just supporting the top guy: they wanted to give him the power necessary to govern.

While this was certainly a notably popular effort when compared to prior third-party runs, it was still questionable whether or not this would be successful. While Ross Perot’s numbers were surging in national polls, he also wasn’t technically affiliated with any political party at the time, meaning that riding his coattails successfully would be more challenging than as a Democrat or Republican, who would both have the ability to ride any existing presidential coattails with relative ease. Even if Ross Perot did win the presidency in November, it wasn’t entirely clear that the Independence Party would be able to join him in Washington D.C.

All things considered though, this wasn’t the worst problem you could have. Unlike other failed third parties, the foundation of the Independence Party was built on a popular movement that was clearly being observed on the national stage. While the Greens have never been able to field a candidate that gets above 5% of the vote, the guy that the Independence Party claimed as their ally was polling ahead of the Democrats and Republicans in national polls. Even if only half of his support trickled down to them, it would still represent a pretty massive constituency of voters that could wield real influence on the statewide level. At the very least, they were on track to be a strong third-place party, right?

Well, as the campaign progressed, even that was beginning to be put in doubt.

Death’s Door? Already?

While most people remember Ross Perot’s 1992 campaign for putting up a very solid independent performance when compared to other non-duopoly efforts, there is a part of the story that often goes under-discussed. While his share of the popular vote was certainly sizable, it was also a massive underperformance compared to what could have been. As I said before, Perot was once polling first place, even managing to near 40% of the vote in one poll. His final result ended up being nowhere near close to that, and it wasn’t even out of fear of vote splitting, the main thing that usually takes down surging outsider efforts. The reason was far more simple: his campaign turned into a complete and utter dumpster fire.

As Ross Perot began to assume the position of front-runner, his campaign came under an increased level of scrutiny by the media and opposing politicians. There were questions over his business dealings. There were attacks on his past support of the Vietnam War in the 1960s. There was even some mockery over his job as a paper boy. Once Perot became the frontrunner, there was an endless amount of questionable and embarrassing stories that came to light from the national press. For the first time, his seemingly clean campaign had some dirt thrown on it.

While most candidates prepare for this potential onslaught before they ever enter the ring, it became clear early on that Perot did not take this important step. Over the course of his status as a frontrunner, he would make an endless amount of strategic mistakes and rhetorical gaffes, which only saw his support decline further and further. Eventually, he was removed from his position as a frontrunner entirely, running well behind both of his main two opponents seemingly overnight. His advisors, long frustrated with Perot’s lack of interest in what they had to say, had finally had their breaking point upon seeing his declining poll numbers. They gave him three options: take their advice and run a real campaign, don’t take their advice and the advisors go, or drop out of the race entirely. In their last-ditch effort to save the campaign, they gave Perot an ultimatum, one that would determine the future of his effort. What did Perot decide to do?

Unexpectedly, he would go with the third option, announcing on Larry King Live that he was going to be dropping out of the presidential contest. While he would claim the reason was due to the Electoral College being a barrier, practically everyone knew that the real reason was that he realized the writing was on the wall. When thinking about the ultimatum, he quickly jumped to the conclusion that he was not going to be winning the race. Not only were his own numbers declining, but one of his main opponents, Democratic nominee Bill Clinton, was surging around the exact same time. This cut deep into Perot’s numbers, and it soon became clear that even if he did run a perfect campaign going forward, it was going to be near impossible to recreate the magic in time for the election. Despite being on track to be on the ballot in all 50 states, he just didn’t see a path forward anymore.

This was terrible news for the Independence Party. What once looked like the start of a unique third option that could occupy a clear space in statewide politics now suddenly looked like it was on death’s door. Not only did they not have a national spokesman for their ideas anymore, they still didn’t even have a brand of their own either. While they certainly had a large pool of voters they could have pulled from, that came entirely off the back of Perot’s movement, not anything they had created independent of him. Having only existed for just a few months by that point, they were too new to the scene to truly have an established base of support purely on their own. They needed a launch point, a strong result that could have propelled them into something interesting. And with Perot no longer running on the top of the ticket, this vision of a strong third movement was on track to be nothing more than a fantasy.

Over the course of the next few months, the Independence Party was slowly fizzling away. Most media coverage during this time was spent covering Bill Clinton, a charismatic southern baby boomer and masterful politician who began to take massive leads in the polls over incumbent president George H.W. Bush. Despite being part of the two-party system himself, Clinton quickly took Perot’s mantle as the change candidate in the race, making him a very attractive option to many burnt Perot supporters. This only served to cut deeper and deeper into the Independence Party’s already waning appeal, as the Democrats looked like they were on track to ride Clinton’s coattail appeal into a massive majority in November. For a while, it looked like the future of the Independence Party was set: it was on track to be yet another failed third party.

But if there’s one thing you should know about elections, it’s that October is full of surprises.

Going into October, not many people had really expected to race to shake up in any meaningful way. While the October surprise could still have had some impact, the chance that Bill Clinton’s double-digit lead was going to be jeopardized by this point was seemingly near impossible. Most of the things that were supposed to benefit Bush, such as the RNC convention bump, didn’t seem to do anything to dent Clinton’s massive lead. After living in the White House for 12 years, people were just tired of Republicans being in there, and with the economy going south and lacking charisma of his own, Bush didn’t inspire confidence.

This is where you may assume I’ll say that everything changed on October 1st, which is when Ross Perot announced to the world that his campaign was back on. I don’t blame you for thinking that, but this really wasn’t seen as that big of a deal. After all, he was out of the race for months at that point. His previous standing as a frontrunner was long gone by this point, and most polls indicated that if he were to re-enter, he would struggle to even poll above 10%. In the eyes of many, he had broken their trust and killed off a movement that was surging because he couldn’t handle himself. Even if they did know he re-entered the race, it was going to take a lot to get those people back on his side, especially in the face of Bill Clinton. In retrospect, the task of building up the support needed to win after all of that was virtually impossible.

To his credit, however, Perot would spend October trying as hard as he could to re-create the magic. Qualifying for all three of the presidential debates, Perot would participate in all three of them, giving him a national spotlight next to his main two opponents. While his debate performances weren’t absolutely spectacular, he did emerge as the winner in the first and third debates, which would help bring back some of his past appeal. This began to be reflected in the polls, which shot up to 20% in the aftermath of the debates. While his standing wouldn’t go beyond that thanks to some revelations about his new campaign using loyalty pledges, it did create something of a real base once again. He wasn’t going to win the presidency, but he was going to create a sizable movement.

For the Independence Party, this was nothing less than divine intervention. Once on track to join the slums of the New Alliance and Constitution Party, it once again had its top guy to ride off of. While Perot was not going to win the presidency, his strong performance meant that the Independence Party was successful at chipping off even a quarter of Perot’s support, it was finally going to be noticed by the DFL and Republicans. And with Minnesota’s outsider track record essentially ensuring that Perot would have a strong performance in the state, the party looked like it had a bright future.

The First Breakthrough

When Election Day 1992 finally came, the result was anti-climatic. After leading in the polls by massive margins for months, Clinton would win this race in a landslide, defeating Bush by a massive electoral college margin of 370-168. After 12 years of near uncontested Republican rule in the White House, Clinton had finally ended his party’s national losing streak, becoming the first Democrat to win the presidency since 1976. While this wasn’t particularly surprising, it was still a pretty big shakeup in national politics in its own right.

As all of that was happening, Perot’s numbers largely went ignored. While his 18.9% number was certainly a massive chunk of people, he also failed to win even a single electoral vote, the thing that matters more than anything else in winning the presidency. Compared to the high 30s numbers he was pulling in the summer, his final showing just looked weak. While future elections would make this performance stand out, for the time, it just wasn’t that shocking.

Despite hardly anyone noticing, however, this is where the seeds for the Independence Party truly began to grow.

Minnesota’s result in 1992, far more so than even the national result itself, was never in serious doubt. While Republicans swept the country throughout the 1980s, Minnesota was always loyal to the Democrats, even being the only state to vote blue in the 1984 Republican landslide. It was a deeply Democratic state, and Bill Clinton was never on track to lose the state at any point, even at the very beginning of the race when he was polling far behind Bush. This was reflected on Election Day, when Clinton defeated Bush by an 11.6-point margin, sweeping most counties in the state and every congressional district in the process. In terms of margin, it was yet another solid victory for Democrats in the North Star State, continuing their long-time tradition of domination on the presidential level.

However, one thing you will immediately notice is that despite winning the state by double digits, Clinton’s actual percentage of the vote was minuscule. While his victory was certainly still strong, his final percentage of the vote only amounted to just 43.5%, the lowest amount scored by a presidential Democratic nominee in the state since 1928. It was even lower for Bush, who would only score just 31.9% of the vote, the lowest amount for any presidential Republican nominee since 1936.

The reason for this is also something you will probably immediately notice: Minnesota’s outsider streak came through.

While Perot would get 18.9% of the vote nationally, he would score 24% of the vote in Minnesota, making it his best state in the Midwest by a wide margin and his 10th-best state in the nation overall. Most notably, some of his best counties in the state came from the Twin Cities suburbs. Whether they were Republican-leaning counties like Carver or Wright, or Democratic-leaning counties like Anoka or Washington, Perot would consistently exceed his statewide margin in all of these counties. While he would struggle in the urban parts of the Twin Cities and the traditionally Democratic Iron Range, his strong suburban support allowed him to end up with a 24% number. All in all, a very solid performance by the Texan businessman.

With all of that being said, how did the Independence Party do? Well, as I mentioned previously, they only actually ran in one race, the contest for Minnesota’s 6th congressional district. This was supposed to serve as a test run to show off Perot’s appeal, and in the process, build a party of their own off of that. It was a risky choice, but when the results had come in, it was clear that it had paid massive dividends.

Minnesota’s 6th district, which represented the western and eastern Twin Cities suburbs, proved to be the best launching point district the party could ask for. It was one of Perot’s best spots in the entire state, giving Dean Barkley far bigger coattails than he otherwise would have had. This was shown clearly in the final numbers, which saw Barkley acquire 16.1% of the vote, almost entirely off the back of Perot voters.

Despite being a brand-new party, despite Perot himself not even being affiliated with the party, and despite Dean Barkley being relatively unknown, they would manage to put up a very solid third place showing that instantly got them new attention from those in the political world. Unlike Perot’s showing, there was no conversation about underperforming compared to past expectations. Outside of Perot supporters, most people hadn’t even heard of these guys before the election. Many hardly even knew that they had connections to Perot and his movement at all. All they knew was that it was a new third party that had just put a massive overperformance not seen anywhere else in the state. This performance, while technically worse than Perot’s showing in the district, had served its purpose perfectly. Suddenly, people began to look at them as an entirely new force, more than just a symbol of Perot’s movement. Other than outright winning the race, there wasn’t a lot more the party could ask for.

But while this performance was solid, there was still a ton of work ahead of them. While their 16.1% number was notable, it also didn’t mean anything in regard to their official party status. In order to go beyond just riding the coattails of an independent presidential candidate, they needed to be regarded as a serious party in their own right, something that any third party is always going to struggle with. One of the ways to do this was to actually be regarded as such by the government of Minnesota, which required earning at least 5% of the vote in a statewide election. Not only would it give them an attention boost but it would also allow them to be treated to many of the same benefits that the DFL and Republicans had. While this wasn’t a guaranteed ticket to success, it was going to be an essential step to going forward.

So, there was now a new mission ahead of the 1994 elections: earning major party status.

Just Another Reform Party

With their new goal laid out, all that was left was to figure out what would be the easiest path to achieving it. Ideally, you would want to run in a race that doesn’t have another third party running already and also not against a popular incumbent. Simple enough, right?

Well, there was one problem with this, it didn’t look like such a path was open at first. Looking at the statewide races up for grabs in 1994, they all seemingly fell underneath one of those two categories. In the case of the U.S. Senate seat, Governorship, Attorney General, and Secretary of State, all of them featured incumbents well on track to win their races quite relatively easily, making an effort to build a strong third party showing that much more difficult. The other two contests, State Auditor and State Treasurer, suffered from the other problem I mentioned: there were already strong third-party candidates in the running for these seats under the growing Green Party. Ideally, you don’t want to be running against other third parties if you are trying to establish a coalition needed to get 5%. While it wasn’t impossible they could still get major party status in these races, the hill they would need to climb in order to do so would be pretty steep.

Fortunately, however, good news would come for the party, when it was announced that the incumbent U.S. Senator David Durenberger was going to retire. And with no other strong third-party candidate running in the race, it gave the Independence Party a perfect lane to fulfill their goal.

But in order to make sure this effort was ultimately successful, the Independence Party would once again nominate Dean Barkley as their main candidate, the most well-known member of the party, and the only one with an electoral record to speak about at all. This move was a smart play by the party, allowing them to play the role of outsiders to the system while also not coming off as unserious loons. While Minnesota’s friendlier attitude to third parties could have suggested that the party would get to 5% regardless of whoever they nominated, the party wasn’t going to take that supposedly destined event for granted. After all, this political environment was nothing like 1992. With no Perot running, this would be the first time that the party would have to rely on its own image. There was not going to be a top national figure to ride off of. They just had themselves. So how did they do?

When Election Day came in 1994, this cautious attitude would prove to serve them well. While the result of the Independence Party was overshadowed by the massive red wave that swept the country, this election would be the one where the party would see its official breakthrough, becoming a major party after earning more than 5% of the vote in the U.S. Senate contest. Not only was this a massive step forward in regard to recognition and funding, but it also put them a step ahead of the other third parties running in the state that year, all of which failed to get above 5% in the other statewide races. In that respect, the Independence Party stood alone, becoming the most popular third party in the state in the process.

That being said, remember when I told you that their cautious attitude in nominating Barkley served them well? That was because the final result did not see them cross the finish line with a lot of leftover stamina. While they still succeeded in beating the 5% benchmark, it was only done by earning 5.4% of the vote, just barely over the number required and far lower than Barkley’s 16.1% number in 1992. While they still pulled off an undoubtedly big achievement, they did it in the most underwhelming way imaginable. Sure, it made them a step ahead of the other third parties. But is that really such a big deal when those other parties were already getting in low single digits? How exactly does that paint a future of a strong, third force in statewide politics?

This problem would persist for the next four years as it struggled to find itself go any further than just barely scraping by as a major party. Heading into 1996, they would once again run Dean Barkley for the U.S. Senate, this time going up against incumbent DFL Senator Paul Wellstone. In theory, the 1996 election should have seen themselves break from this somewhat. Not only was Ross Perot running on the top of the ticket again, but he would be doing so as a fellow party member. Recognizing the difficulties that come from running as an independent, Ross Perot would create his own political party, the Reform Party, to compete with the Democrats and Republicans ahead of the 1996 election. The Independence Party immediately jumped on board with them, renaming themselves the Reform Party of Minnesota and making themselves an official statewide branch of the National Reform Party. While Perot wasn’t expected to poll nearly as high as he did in 1992, you would at least expect Barkley to have a better ability to ride off of his coattails. But did they actually pull that off?

Well, not really. Much like the election itself, the result in Minnesota was not a shocker. Bill Clinton would once again win the state, this time by a landslide margin of 16.1%, winning all but 11 counties in the state in the process. In comparison to his lackluster percentage of the vote in 1992, Clinton would manage to win the majority of the state in a three-way race, leaving both of his main opponents in the dust. Much like the nation itself, Minnesota was satisfied with the President, and living up to its Democratic tradition, elected them back in the White House.

Once again, however, Minnesota would live up to its outsider tradition too. Just like in 1992, Perot would manage to pull off a better performance in Minnesota compared to the rest of the nation, earning 11.8% of the vote and making it his seventh-best state in the nation. While the vote drop was stark compared to 1992, it still represented a sizable chunk of the vote, one that Barkley should have been able to ride off of with relative ease. But when the U.S. Senate results came in, Barkley only pulled 7.0% of the vote, yet another underwhelming performance that didn’t project a lot of energy. While it was a numerical improvement from 1994, it didn’t exactly paint the picture of a party that could really hold its own. More than anything, this election proved that they had become stagnant. After four years, they still held the exact same numbers as they did in 1992. They hadn’t shown any real growth of their own. They were just another Reform Party. And like the Reform Party itself, it was slowly beginning to be written off, becoming just another footnote in the history of failed third parties.

But just as it seemed like the Independence Party was dead, a meteor would hit the planet.

Jesse “The Messiah” Ventura

When looking back at uneventful and forgettable midterms in modern history, there probably isn’t a lot that can compete with 1998. Occurring during a time of economic boom and high marks for the Clinton administration, there wasn’t really a whole lot for people to complain about. While midterms usually resulted in big gains for the opposition party, the Republicans had already gained control of both chambers of Congress in 1994. Adding onto their unpopular impeachment effort against Bill Clinton, there wasn’t really much they could gain out of this election. Thanks to that, the 1998 elections go almost entirely under-discussed compared to their Republican Revolution 1994 brother.

Well, with one massive, massive exception.

If you know the result of literally any election in 1998, it’s probably in the North Star State. In just one night, the entire two-party system was flipped on its head, becoming a symbol of what a post-duopoly world could have looked like going forward. To Minnesotans, it looked like the beginning of a movement, one that had the capacity to compete with the two other parties like the old Farmer-Labor Party did.

And the Independence Party was right in the middle of it. But how?

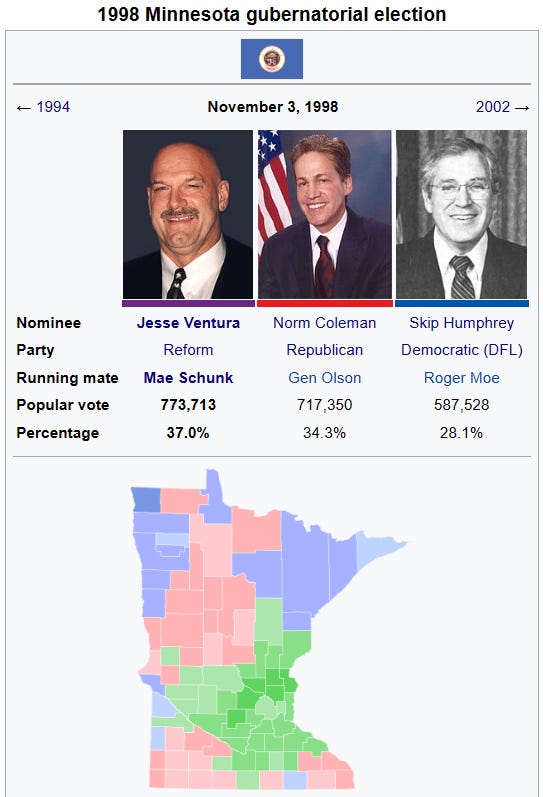

Going into 1998, it didn’t look like anything new was on the horizon for Minnesota politics. While the retirement of incumbent governor Arne Carlson guaranteed that the state would at least have a new governor at the helm, neither the Democratic or Republican options looked like real shakeups to the game. For the Democrats, they decided to reach back into the mid-20th century, going with incumbent state Attorney General Skip Humphrey, son of the former Vice President himself. For Republicans, they decided to go with St. Paul Mayor Norm Coleman, a former Democrat and Paul Wellstone backer who had only been a Republican for just over a year. This made both parties’ strategies pretty obvious: ignore the enthusiastic base and play it as safely as possible.

As all of that was happening, the Independence Party was struggling to find its footing. After 1996, the party found itself in limbo, unable to build its base past what it already did in 1992. With Ross Perot slowly fizzling out of the national scene and Dean Barkley not willing to run another sacrificial campaign, it left the Independence Party with no real leader for their cause. It was possible that this could have been the death of the party altogether. After all, it was leaderless, looking increasingly unserious, and still didn’t really seem to have any committed ideology to hold up besides generic populism. They needed a messiah, and for a while, it looked like they weren’t going to get it.

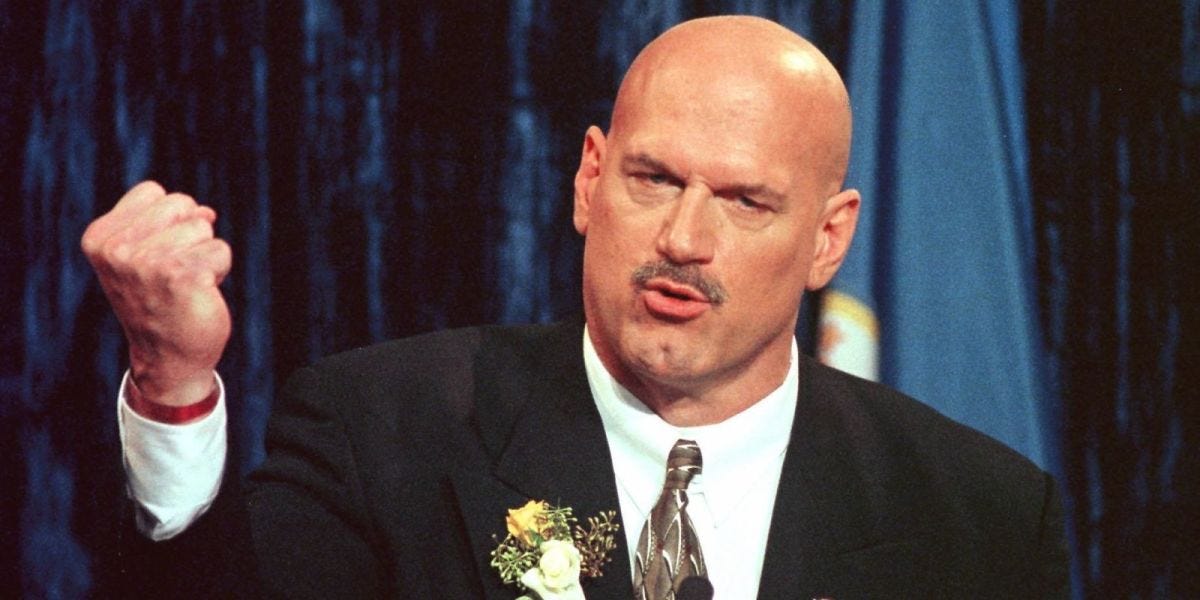

But from an act of god, the party would soon find him. A man who could bring them back from impending death and give them the jolt of energy they needed. A man who could turn it into the third-party force they had dreamed of for six years. A man who had a bombastic brand he could bring over to the party. Yes, it’s the man himself. It’s Jesse Ventura.

This is probably the part most of you have been waiting for. I can’t say I blame you for that either. Even among a group of outsider politicians that come from the land of 10,000 lakes, he truly stands out among the pack. From being an underwater demolition team member, wrestler, sports commentator, actor, talk show host, mayor, and governor, he has a massive number of resume items he has collected over his many decades in public life. It’s very likely you’ve seen this man somewhere, especially if you are even a little bit interested in politics or big into WWE. From a trivia standpoint, it’s always fun to mention that Minnesota once elected a former wrestler as its governor.

But how exactly did he do that? How did this man go from being a wrestler to completely shattering Minnesota politics overnight?

After leaving the WWF in 1990, he would officially begin his political career, making a run for the mayorship of Brooklyn Park, a large suburb just outside of the Twin Cities. It was here where he showed early signs of real political skill, managing to topple his city’s long-time incumbent mayor by a landslide margin. While his low-profile office meant he couldn’t build up much of a political profile yet, it allowed him to point to some level of experience he had to prove he wasn’t entirely unserious, giving him an edge that many other outsider politicians don’t have.

After retiring as mayor in 1995, Ventura would slowly begin the framework to run for Governor of Minnesota. A fan of Ross Perot and his party, he would officially announce his candidacy for the Independence Party nomination. For the first time, it wasn’t Dean Barkley that would be the head of the ship. Initially, this led to virtually no one taking him seriously. Sure, he was a former mayor. But he was the mayor of a suburb that hardly anyone cared about. What made him think he was qualified to be the Governor of Minnesota? Shouldn’t he be managing a WWF match with a Bob Marley shirt on?

Ventura, undeterred by these dismissals, would invest a considerable amount of time and money into a strong grassroots campaign. Taking from the Wellstone playbook, he would campaign in a bus that toured the entire state, partaking in aggressive retail politics in the process. Just like Amy Klobuchar was doing in her small race, Ventura would also take heavy advantage of the internet, a portion of advertising that his two main rivals had not bothered to invest in. Finally, knowing how few TV ads he could afford to run, he would make sure to take full advantage of them. His most popular ad, simply titled “Action Figure”, would play right into his celebrity image as “The Body”, portraying him as a superhero-like figure dedicated to fighting special interests and two-party gridlock. While this could have made him look like an unserious person in another race, it would prove to be beneficial to him when his main two opponents were seen as boring, establishment options picked by the parties to simply beat the other.

In a world full of average simple men, Ventura had managed to stand out. After years of basic governors, the people of Minnesota wanted an outsider, and since the two main parties weren’t giving them one, many had begun flocking to Ventura. Over the course of the next few months, the polls would slowly see his numbers tick up further and further. First, he got out of single-digit hell. Then he began to poll into the low 20s. Then as the debates were starting, he pulled into the high 20s. After strong performances, he would pull into the low 30s, even managing to finally poll second to Coleman in some polls. Finally, as Election Day was just around the corner, he even managed to get within the margin of error. Over the course of just a few months, Ventura had gone from a complete political nobody to being a serious threat that neither Humphrey nor Coleman had ever expected. The possibility of a Ventura administration was no longer a cheap joke. He was well on track to get at least 2nd place, and depending on how the night went, even potentially manage to take the Governor’s Mansion itself.

At least, that’s what the polls were saying. It’s just polling. While it can be useful, it doesn’t actually determine how people are going to vote on Election Day. People may say they’ll vote for Ventura when asked in polls out of frustration for the DFL and Republicans, but when they actually go to vote, they’ll think about it logically and realize that any hope for “The Body” actually being in power is just wishful thinking. They’ll realize that all of this is just a charade, and vote in someone with real experience. Surely, they won’t go to the polls to elect a wrestler just because they are mad at the establishment, right?

Right?

For the first few hours of Election Night 1998, the result was expectably stale. While the Republicans looked well on track to hold control of both chambers of Congress, they were also well on track to not make any gains in either chamber. The Democrats, who had spent months defending the popular Clinton administration from an unpopular impeachment, had successfully held their own and prevented another 1994-esque landslide against them. For the first few hours of the night, that looked like it was going to be the main story: an example of a party overreaching its hand and killing off its natural midterm advantage. While it was interesting, it wasn’t exactly a flashing headline either.

Then the polls in Minnesota closed.

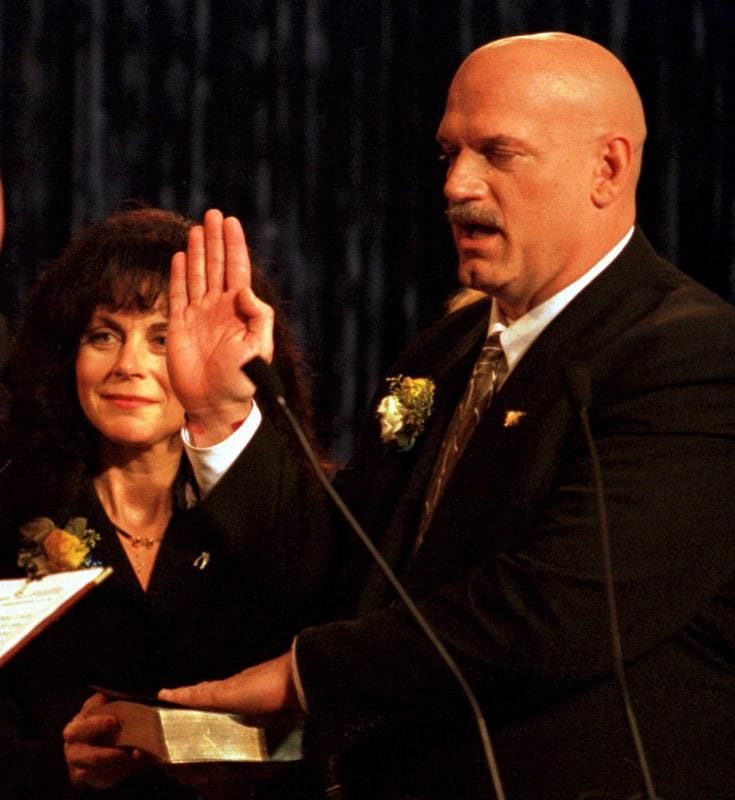

The results would take a while to come in, and the numbers would be very close for most of the night. But people could tell what was going on from the very beginning. Just like it did 8 years prior, Minnesota would end up being the standout result in an otherwise unremarkable year. Despite being dismissed by practically everyone just three months prior, despite only spending less than half a million dollars, and despite running against two highly credible and qualified politicians, Jesse Ventura had managed to crash into the political world, winning the Governor’s office with 37% of the vote. As Ventura himself said during his victory speech, they had managed to “shock the world”, even comparing his victory to Muhammad Ali’s win over Sonny Liston in 1964.

For the Independence Party, this could not have been better news for them. Sure, he was their only success on the ballot that year: their other candidate efforts went down in flames. But they still had their own Governor! Once leaderless, the party finally had someone they could point to as their guy and by extension, build a real base of support off of his brand. Unlike almost every other Reform Party in the country, they no longer needed Ross Perot to stay afloat and scrap by. They could actually make something real, building a real force that the DFL and Republicans would have to take seriously. It was a tall order for Ventura, but so was winning the Governor’s office itself. He had already shown off an ability to conquer very steep political mountains. If anyone could do it, it should have been him. Surely, he can bring the party newfound success, right?

The Untold Disaster

Whenever people talk about Jesse Ventura, you’ll probably hear a mention of how he managed to become Governor of Minnesota in the late 1990s. If you know a little bit more, you may even know how he managed to win that campaign, shocking the world in the process. But even many of his biggest fans today probably don’t know a whole lot about one of his most important contributions to the world: his actual tenure as Governor of Minnesota.

This isn’t that surprising. You don’t usually hear much about it in local or national news, they typically tend to focus on how he actually managed to win that office in the first place. You don’t even tend to hear it from Ventura himself, instead just listing his four years as Governor as yet another item on his massive resume. His tenure is something that goes significantly under-discussed, especially when you consider the impact his administration had on the future of the Independence Party. That being when you analyze his four years, you come to one inescapable conclusion about it: his tenure was a total disaster.

When I say this, I want to make something clear: I’m not referring to his policies. As someone on the left, there are some things to appreciate about his tenure, from his investments into high-speed light rail, his early support for LGBTQ+ rights, and protecting the high levels of funding that public schools get in the state from Republican cuts. While I wouldn’t have voted for him, I don’t believe that his governorship could be considered anywhere near the worst, especially when you consider the difficulties of being a third-party governor in the face of uni-party opposition in the State Assembly.

What I am referring to are his actual skills at being an incumbent politician. Much like Ross Perot, he didn’t know how to handle himself with the press, frequently getting in fights with them whenever possible. The first notable example of this came just a few days after he was sworn in, when a reporter had jokingly asked him about his singing ability at a concert he had been starring at. Instead of going along with it or ignoring it, Ventura would respond negatively to it, immediately killing the honeymoon period the media had with him and giving an early sign of his poor relationship with them over his four-year tenure.

This bad relationship with the media also carried over to the legislature. With Democrats controlling the State Senate and Republicans controlling the State House, it was always going to be a challenge for the wrestler-turned-governor to get work done here. But Ventura did absolutely no help to himself in this regard either. While he was able to work with them somewhat early on, his relationship with them over the years only got worse and worse. Over time, it became clear that he had basically no allies in the legislature at all, and virtually all of his vetos would be overruled by the legislature. This was especially bad during the last few budget negotiations when Ventura got basically nothing done and was effectively forced to go along with whatever the other parties wanted.

Near the end, Ventura could pretty much only wave his middle finger at the legislature, with his only notable exercises during this time being when he moved out of the Governor’s Mansion and began to do his work at his home in Maple Grove, something that came right after the legislature voted to increase security. On top of this, he would also lift a middle finger specifically at Democrats, appointing Dean Barkley instead of a Democrat to the vacant U.S. Senate seat after Paul Wellstone was killed in a plane crash in late 2002, describing it as a response to what he saw as the politicization of a tragedy. While these both made him look petty, it was what he was limited to by this point. Despite being the governor of the state, he had basically no role in any legislative negotiation.

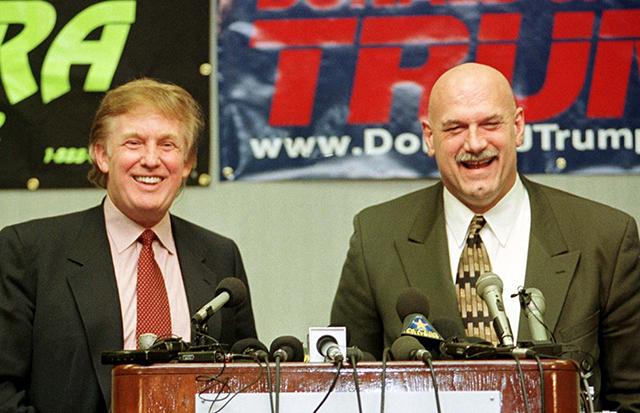

These problems would be bad enough. You don’t want to serve as a lame duck far before the actual lame duck period. But the icing on the cake would be the fundamental problem that ultimately killed Ventura’s governorship: He just looked unserious. Throughout his entire governorship, Ventura gave people in the state the image that he was more concerned about keeping up his personal brand and name in national politics than actually working on behalf of Minnesota. Whether it be hosting WWF games, hanging around with Donald Trump over his 2000 Reform Party run, or commentating over an XFL game, he looked like he was more interested in having fun than doing the hard work. While this eccentric celebrity image worked in his 1998 campaign, doing this while the governor of the state was an entirely different ballpark. People expected him to take his job seriously, but it didn’t look like he was.

This, more so than anything else I listed, was what killed his governorship altogether. While he entered office with a 73% approval rating, he would enter 2002 with a 43% approval rating, a massive drop that basically killed any hope of winning a second term. Deeply frustrated with the job and seeing the writing on the wall, Ventura decided to bow out of the 2002 campaign, leaving his party with no clear leader. Once a potential crusader for the death of the duopoly, “The Body” had been reduced to a sideshow, serving as a perpetual lame duck until someone more serious could be sworn in.

Obviously, all of this was terrible news for the Independence Party. The guy they had staked their entire party on turned out to be a total dumpster fire in the eyes of the public. After spending years trying to prove they could be a serious force, their perception would be slowly shattered as it became clear that Ventura didn’t really care much for his own job. While they were the fresh new kid on the block in 1998, by 2002 they had become the laughingstock of Minnesota politics.

You may think this would be the time for the party to look towards a national figure to get things in order, but even that wasn’t an option anymore. The Reform Party had never had a clearly defined ideology, it was mostly just a big tent that was only really united by generic populism, making it susceptible to being taken over by outside actors. While Perot and his centrist faction would hold the party together in 1996, it would soon begin to collapse as soon as he left, being taken over by Pat Buchanan, a far-right extremist, ahead of the 2000 election. This resulted in Ventura, alongside his friend Donald Trump, officially abandoning the Reform Party in 2000, bringing the statewide party with him and officially renaming it back to the “Independence Party”.

While this was the best call they could have made, it still put them in a terrible spot. While they technically didn’t need one, they no longer had a national figure to look up to, setting them back considerably in regards to being seen as serious actors. And since Ventura was unpopular, that meant that there was basically no figure they could look to. Despite holding the Governor’s office, the party was once again leaderless, with them well on track to be totally wiped out in 2002.

But if there’s anything we have learned about our friends over at the Independence Party, it’s that we should always expect something bizarre.

Tim “The Future” Penny

Heading into 2002, more so than ever before, the Independence Party had a serious issue in regard to who they would nominate. With Ventura bowing out of the race, and Dean Barkley not interested in re-entering electoral politics, the party looked like it was on track to nominate a complete rando, lacking any kind of experience or brand of its own. They could probably hold onto some support thanks to newfound party recognition, but it didn’t look like it was going to go any further. Tragically for them, it looked like the party was well on track to re-enter single-digit hell.

However, in a rare move for Ventura, he would get himself involved in the process, not wanting to see his party go up in flames immediately after he left. He did this by hand-picking a successor himself, going with former moderate Democratic Congressman Tim Penny, a friend and ally for Ventura’s cause. While the governor would make bad political call after bad political call throughout his tenure, this decision stood out as one of the very few good ones he made. In picking Penny, a soft-spoken moderate with congressional experience, he allowed the party to rebuild some image of seriousness that he had tarnished over the last four years.

On top of this, Penny would be able to run against competition that could make him stand out. His main opponents, Republican State House Majority Leader Tim Pawlenty and Democratic State Senate Majority Leader Roger Moe, both spend most of the campaign running in the arms of their bases, assuming that getting at least 35% would be more than enough to get over the finish line. While neither were radicals by any sense, they also didn’t make that much of an effort to play for moderate voters, giving Penny a clear lane to run in.

Penny, aware that many didn’t take the party seriously, would seek to find the right balance between being an outsider and flexing some of his experience as a congressman. In doing so, he would mostly avoid mentioning or campaigning with Ventura, instead focusing on his record as someone who fought and believed in balanced budgets, civil liberties, gun rights, and other principles of the Independence Party. Despite running with the same party as the incumbent governor, Penny had built an image of his own as “the future”, the one who would take Minnesota into the 21st century.

For most of the campaign, this approach worked out quite well. Most polls had the race tight, with Penny running close to even with both Moe and Pawlenty just a month before the election. For the Independence Party, it was a remarkable sign of recovery. Despite their governor being seen as a failure by most in the state, it looked like they had been able to separate themselves enough from him to not suffer from his failings, while also not straying too far away from what they stood for either. Maybe, perhaps, despite everything, they really could hang on and end the duopoly for good.

However, the last month of the campaign would see this dream dashed. As Election Day came closer and closer, and in light of Ventura’s response to Paul Wellstone’s tragic death, more and more people began to fall prey to strategic voting. While Penny was well-liked, he didn’t have anywhere near the same level of star power or enthusiasm that Ventura did, making his voting base more susceptible to switching sides. Moderate Democrats and Republicans, previously more inclined to vote for Penny, would begin to assess that his campaign was doomed and quickly abandoned him in droves for their own party’s nominee. While they may have preferred Penny’s vision, they hated their biggest rival party much more, which would ultimately be the thing that guided them at the polls. Simply put, while Ventura could beat back strategic voting through his bombastic personality and celebrity image, Penny had no such strength.

Throughout the final month of the campaign, the Independence Party was awestruck. They had no idea what was going on. After months of being solid contenders, why did everyone suddenly start strategically voting? What happened to voting your values? What happened to wanting a third choice? Didn’t Minnesota want a serious outsider?

As the results were coming in, the party could do nothing but ponder over these many questions. While both the Democrats and Republicans would make gains in terms of vote percentage, the Independence Party would see itself collapse, earning only 16.2% of the vote, down a staggering 20.8 points from their 1998 showing.

Sure, they still had a base, and it made up a sizable chunk of the electorate. And sure, they could still play at least a minor role in the politics of the state. But after everything they had achieved in 1998, it felt like a total failure. They weren’t supposed to be the low double-digit third party that people only voted for out of necessity or protest. They were supposed to be the ones that single-handedly took down the duopoly, giving people an example of what a three-party system could look like. But as the results came in, it was clear that this grand vision was fading away. Not even an experienced congressman could save them. While not many noticed at the time, it’s clear in retrospect that 2002 was the nail in the coffin, and it would only go downhill from here.

The Protest Party

Heading into the mid-2000s, the party was more demoralized than ever. While they had technically been in worse spots prior to this, none of them occurred after being in a position to change the rules of the game. Any hope of making serious, sweeping changes to the political system had been completely squandered. They had built no party infrastructure, no precinct-level organizations, no local investment, nothing. While their name recognition and moderate brand meant that they still had a base larger than most third parties, that wasn’t what they were made for. They were nothing more than a protest party for moderates upset with their nominee, essentially guaranteeing they would never have a big win again.

Over the course of the next decade, this role would only serve to be more and more firmly established. The most obvious example of this was in 2006, taking place in the Minneapolis-based 5th congressional district. With the longtime incumbent Democratic Congressman Martin Olav Sabo deciding to retire in early 2006, the Democrats would nominate a progressive firebrand, a state representative named Keith Ellison. This angered many moderate Democrats in the district, who felt unrepresented by Ellison. Since these people did not wish to vote for the Republicans, they would flock over to Independence Party nominee Tammy Lee as a protest vote, with Sabo himself donating to her candidacy. While Ellison would still win the race easily thanks to the district’s strong Democratic lean, the protest vote would amount to 21.0% for Tammy Lee, nearly beating out the Republican numbers in the process. While this was undoubtedly a big number for the Independence Party, it also wasn’t built on anything they actually did. They were just in the right place at the right time, it didn’t exactly project much confidence.

This is a story that would see itself repeated time and time again over the next few years. There’s Dean Barkley's 15.2% showing as a U.S. Senate candidate in 2008. There’s Tom Horner’s 11.9% showing as a gubernatorial candidate in 2010. There’s Bob Anderson’s 10% showing as a congressional candidate for Minnesota’s 6th district in 2008. Really, I could keep going on and on, but I think you get the point. More than anything, the Independence Party was a protest vote for moderates, essentially just a name they could sign onto when the other two parties weren’t giving them what they wanted. While this basically guaranteed they’d never be in power again, it at least allowed them to keep their status as a major party. Sure, it was demoralizing, but at least it couldn’t get any worse.

But if there’s anything we have also learned about our friends at the Independence Party, it’s that you should never underestimate the ability for things to get worse for them.

The 2014 Reckoning

Heading into the 2010s, it looked like the Independence Party was on track to continue its status as a distant but clearly defined third-place party. While their impact on state politics was close to nothing thanks to having practically no infrastructure, at least they could still reliably get at least above 5% of the vote. Hell, if they managed to serve as a spoiler, it could even force one of the parties to moderate for votes, theoretically allowing some of their ideals to come into play. While their future was by no means bright, it didn’t look like it was going to change much either.

But as the 2014 elections approached, the party’s lack of organization and clear leadership had finally seemed to catch up to them. First, while their previous statewide candidates held at least some name recognition and endorsements, their nominee for governor, Hannah Nicollet, was a complete nobody, unable to even clear the threshold needed to get public funding support. Secondly, their preferred U.S. Senate candidate would go down in flames to Steve Carlson, a hard-right Tea Partier the party was forced to disavow, falling victim even further to claims of unseriousness. Most importantly, however, both of them were going up against very popular DFL incumbents, ones who happened to have a strong appeal with moderate voters who were typically more inclined to vote for the Independence Party.

All of this combined into an election cycle seen as the final death knell for the party. Almost all of their past top figures didn’t bother to campaign for Nicollet, with some even endorsing the DFL or Republican nominees in these races. There was no energy, no organizing, no enthusiasm, no experience, not even any protest voting. There was no base left, nowhere to go from here. After holding major party status for two decades, they were well on track to lose it all in just one night.

As the Election Day results rolled in, it became clear that the party was finished. While the Secretary of State nominee would manage to get close to 5%, no one else came anywhere near the mark, relegating back to minor party status for the first time since 1994. After years of relying on protest votes and ignoring organizing, they had finally realized what many others had before: they had to build a foundation beyond just the people themselves. This is something the party ignored for twenty years, and after years of defying political gravity, it was finally over.

Just Another Third Party

As I said at the beginning of this piece, if you have only started focusing on Minnesota politics recently, you probably have no idea who these guys are. That’s because if you look at any recent election result in Minnesota, you’ll notice that the Independence Party name means basically nothing. If they even bother to run a candidate, they usually struggle to poll above 1% of the vote, falling far behind even the one-issue marijuana legalization parties that serve as nothing more than pro-GOP vote splitters. Even Jesse Ventura, a long-time hater of the two-party system, cannot be asked to support them anymore. At this point, there is nothing that distinguishes them from the Greens, Libertarians, or Socialist Workers parties.

But when you actually take a look at their history, you’ll learn more than just the fact that they were once a lot more than just another third party. You’ll also learn a valuable lesson in politics and campaigning: you have to do more than just suck up to a single man. If you want to be a successful party and movement, you have to actually build the infrastructure necessary to still hang on even if your popular figurehead leaves the game. Otherwise, you will fizzle away into nothing, relegating yourself to the dustbin of history.

The Independence Party didn’t fail because people didn’t want a third party. It didn’t fail because of its ideology, its ideas were shared by a large chunk of the population. It failed because it didn’t try to win. Sure, they would sometimes nominate big names for statewide office, but they would never go any further. Even at the height of their power, they never made an effort to contest every election they could, never made an effort to work on the local and precinct level, and never made a significant effort to properly weed out extremism. Most importantly, however, they never made any effort to change the game away from being a duopoly. In doing so, they squandered an opportunity to make real change, setting back the third-party movement in the state for decades.

While I don’t personally mind this development as a DFL voter, I do think it’s important to take the lesson at heart when it comes to political activism and work. You just have to put in the effort. Never waste an opportunity when given one, and never just assume that popular people will carry you all the way. Otherwise, you’ll end up in a spot just like the one the Independence Party finds itself in, pure limbo and irrelevancy.

Or, as I would put it, just another third party.

Really good article!