The Bizarre 1990 Minnesota Ticket Split

How an otherwise unremarkable midterm election became something of note in the North Star State

When it comes to the presidency of George H.W. Bush, there are quite a lot of interesting things to talk about. Whether it be his handling of the situation in the Persian Gulf, the breaking of his key 1988 promise to never raise taxes amid an economic slowdown, or even just the fact that he really hated broccoli, there are both funny and important things to bring up about the nation’s 41st president.

However, the 1990 midterms, the only midterm to occur under his presidency, is not one of these notable things. Despite midterms typically resulting in the blowout of the president’s party, the opposition Democrats were not in a prime position to make major gains. Being out of power in the White House for ten years by that point, the party had already made many of its big gains in the 1982 and 1986 midterm elections, meaning that there wasn’t really a lot more ground they could cover in that regard. On top of this, the president himself was quite popular, with Gallup polls the day before the 1990 election giving him a solid 58% approval rating. Simply put, this just wasn’t going to be an especially big win for the Democrats. They were likely going to hold onto their already established power, but it wasn’t going to be a blue wave either.

And on election day 1990, that is exactly what happened. While they maintained their strong majorities in the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate, they would struggle to make any substantial gains, only having a net gain of seven in the House and a net gain of one in the Senate. While the Democrats were definitely happy that Bush’s high marks didn’t cause losses within their own ranks, they were still disappointed they weren’t able to make a bigger mark on this election. For that reason, the 1990 midterm elections often go under-discussed. There just aren’t a lot of notable things that happened here.

Well, with at least one exception.

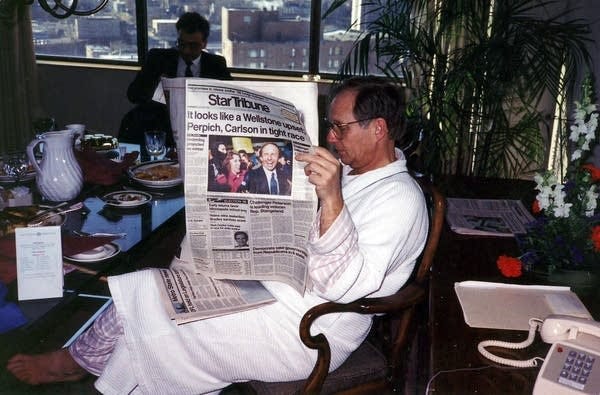

Despite most other states having unremarkable status quo affairs, Minnesota would see itself do some of the most bizarre ticket splitting imaginable. In one corner, the state of Minnesota would be the only gain Democrats would make in the U.S. Senate, which saw Democratic candidate Paul Wellstone defeat the Republican incumbent Rudy Boschwitz. And in the other corner, Republicans would successfully flip the governorship from blue to red, with Republican Arne Carlson defeating the incumbent DFL governor Rudy Perpich.

Initially, it can be confusing as to why these facts are really all that bizarre. Plenty of other states in the 1990 election would also ticket split, from states as big as Texas to as small as Wyoming. Ticket splitting was pretty normal thirty years ago, as the impacts of political polarization were far weaker in the 1990s than they are today. While a Democrat winning Wyoming in any capacity in 2023 would cause a national media explosion, back in 1990, it was just yet another race on the map. So, what made Minnesota any different?

Well, when you take a closer look, it’s immediately clear as to why this election is one of the more interesting ones in Minnesota’s long history. This is because none of what ended up happening on Election Day 1990 was ever supposed to happen. In no world was a Carlton College professor supposed to take down an established Republican incumbent. In no world was Arne Carlson ever supposed to be the nominee to take down the defining symbol of the rural DFL. And most importantly, in no world were these two elections ever supposed to happen together.

So in this article, I want to go over this truly odd result and how it happened. And to do that, let’s start at the beginning.

How the Incumbents Came To Be

Before we get into the challengers in this election, let’s set the stage as to who the incumbents are in this equation, as both of their profiles will be key to understanding how the 1990 results ultimately came to be. In order to do that, we need to establish the political environment that allowed these incumbents to rise to their positions.

Ever since the DFL was created in a 1944 merger, the party had been the dominating force in statewide politics. Whether it be the U.S. Senate and House seats, the statewide offices, or the state legislature, the DFL was consistently beating out the Republicans time and time again in these battles for control. While they would occasionally lose an office or two, their overall dominant position in the state was never questioned.

This dominant position was thanks to many factors, but one of them was undoubtedly due to the leadership figures in the party. Whether it be Hubert Humphrey, Orville Freeman, or Walter Mondale, all of these men played a part in making the DFL the powerhouse it was on both the statewide and national levels. They were incredibly talented politicians who knew how to get results, and their prominence in the state was one of the reasons why the DFL dominated for so long.

However, the influence these leaders would yield over the state would soon come to an end. Orville Freeman, the Secretary of Agriculture under John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, would see his political career come to an end in 1969 when Richard Nixon was sworn into office. Hubert Humphrey, one of the men responsible for the creation of the DFL, would sadly pass away in early 1978. Finally, while Walter Mondale was elected the Vice President to Jimmy Carter, his president’s administration grew to be incredibly unpopular, practically destroying Mondale’s ability to have influence over statewide politics. In just the span of a few years, the DFL had lost many of its best and most effective leaders, and only time would tell when that would catch up to them.

While this was all happening, the DFL had embroiled itself in a number of other controversies as well. The most notable one was how they chose to deal with Mondale’s open U.S. Senate seat after he resigned to become Vice President. Rather than leave the job of Senator up to someone else, the incumbent DFL governor Wendell Anderson decided to make a deal with his lieutenant governor Rudy Perpich, where he would resign as governor, and in return, Perpich would make him the new U.S. Senator. This move was incredibly controversial. It made him look like a ladder climber, someone who was just trying to follow in the footsteps of the famous Mondale. It looked desperate, and voters responded to both Anderson and Perpich very negatively.

This is where the 1978 elections come in. For most states, this was a disappointing, albeit not absolutely devastating year for Democrats. While the Democrats would lose considerable influence, it wasn’t usually enough to knock them out of power entirely. In most states, they maintained whatever influence they held previously, as the truly bad times to come wouldn’t occur until two years later.

But there were some states where the Democrats got absolutely annihilated too. Minnesota was one of them.

The 1978 elections are infamous in the history of the DFL for just how utterly disastrous they were. After decades of being the dominant party, it had looked like the empire completely came apart in one night. In the three most important statewide races, the DFL would completely strike out in all of them, losing both the U.S. Senate seats and the governorship to Republicans.

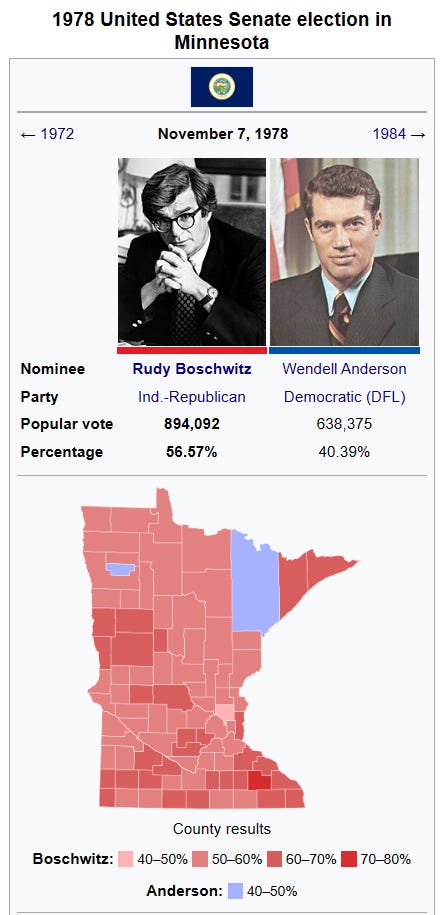

This election, later dubbed “The Minnesota Massacre”, would be where our first 1990 incumbent would be politically established. That incumbent is Rudy Boschwitz, a Plymouth businessman who managed to rise to the GOP plate and defeat Anderson by a solid 16-point margin, the second-largest victory of any Republican in the state that year. He would do this by campaigning as a liberal Republican, appealing directly to liberal DFLers who were dissatisfied with their party’s many woes but also didn’t want to vote for conservative Republicans. It was a brilliant strategy, and it helped him win over practically every county in the state at the same time.

Upon entering office, however, he would not act as the liberal Republican that he campaigned on. While he was by no means the most conservative Senator in the chamber, he was also no liberal either, making himself an ally of the Reagan administration very early on and was practically in lockstep with his party whenever it needed him. Essentially, he was just another Republican Senator, and the liberals who voted for him were pretty annoyed. To everyone else though, it didn’t really strike them as that big of a deal, as in every other respect, Boschwitz was decent enough at being a Senator. This worked out well for Boschwitz in his 1984 campaign, where he would solidly win re-election by 17 points despite Minnesota being the only state to not vote for Ronald Reagan in the concurrent presidential election. The senior Senator had successfully established himself as a potent force in Minnesota politics, and only time would tell when they could take him out.

While Boschwitz was serving out his Senate term, his state’s politics would begin to shift from the GOP blowout of 1978. Unlike Boschwitz, the GOP candidate who won the governorship in 1978 would not prove to have the same level of political competence. That man was Al Quie, and his governorship would prove to be something of a downward spiral from the GOP peak.

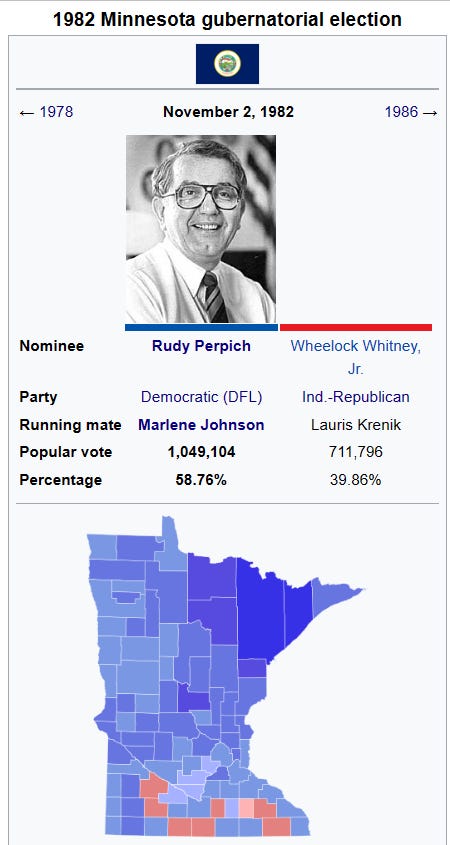

After grappling with various budget issues over his tenure, the governor suffered from consistently low approval ratings throughout his tenure. It would only slip further and further as his governorship went on, eventually resulting in him not running for re-election in 1982. Despite not running for re-election, his poor performance as governor would spark the rise of our next 1990 incumbent. In this case, it was someone most in the state had already written off four years earlier. But in this new political climate, Minnesota had seen him in a way they never had before. It was the lieutenant governor who gave Anderson the U.S. Senate seat just four years prior. Yes, that’s right, it’s former DFL governor Rudy Perpich.

While he was technically the governor of the state before, his political brand would not be properly established until he won a full term of his own in 1982. That political brand was a truly odd one, to say the least. Dubbed “Governor Goofy” by many of his critics, Perpich was known by many in the state for some of his truly bizarre proposals to fix the state’s problems. Whether it be donating a good chunk of his money to the sport of bocce, his strange insistence on building a chopstick factory in the northern part of the state, or even selling the governor’s mansion itself, there was no shortage of unconventional ideas to come out of his mouth.

Despite his goofy reputation, however, Perpich did still have a political brand in the state that extended beyond his critic’s image. Born in the Northern Iron Range, Perpich had always seen himself as a symbol of what he called “Greater Minnesota”, the part of the state not consisting of the populous Twin Cities metro. This was everywhere in his political advocacy, where he would attach himself directly to his Iron Range roots and promise to be a governor for not just the metro, but for Greater Minnesota too.

In the face of dissatisfaction over Republican governance, Perpich would come out of it victorious, winning his 1982 comeback bid by just under 19 points, an incredibly solid performance that would put it as one of the better DFL performances that year. He would pull this off by putting up absolutely insane margins in the state’s rural communities, particularly the Iron Range, where he would put some of the best numbers ever seen for a DFL candidate in history. In winning over his way, he didn’t just win control of the governor’s mansion in St. Paul. He had also established his own unique coalition, and it worked to his benefit all throughout the 1980s.

As governor, Perpich would continue with his political project, bringing large investments into Minnesota in every corner. Perhaps most notable was his efforts to create the famous Mall of America in Bloomington, and inviting Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev for a state visit in 1990. Both of these events stand as the biggest symbols of his legacy today, and whenever he’s brought up in retrospect, those two things are likely going to be the first things mentioned. But he had several other projects beyond that, with the Greater Minnesota Corp in particular being a direct service to his rural base, making it easier for them to establish economic stability. While he certainly did not ignore the metro, his focus was very clearly on Greater Minnesota.

Throughout the 1980s, both Perpich and Boschwitz had become established politicians in the state. While both men were quite different from each other, they both shared the ability to get people to support and turn out for them. After both of them completed their first term, they would both win re-election solidly, giving them a clear mandate to serve out their second term.

For both of them, however, their re-elections would serve as their peak. After their big wins, both of them began to get cozier in their positions, not making nearly as much of an effort to appeal to a group beyond their already established base. After all, it didn’t look like they needed to. They had already won solidly twice. Surely they wouldn’t need to do more than that. They could just coast on their already established incumbency image to win their own full third terms, right?

The Challengers That Weren’t Supposed To Be

Despite the two men starting to become more complacent, it initially looked like neither of them would have to try all that hard to win a third term. While Perpich’s image as a goofy governor was fully established by this point, it didn’t look like many credible challengers were going to step up to the plate. The Republican candidate he was likely going to face off against, Jon Grunseth, was a relatively unknown businessman who didn’t have the ability to inspire any real opposition to Perpich. While many in the metro were growing tired of Perpich, Grunseth was simply too much of a party-line Republican for them. As such, Perpich’s path to re-election looked solid.

Boschwitz was also in a similar situation. He was a well-funded, well-established incumbent who developed a solid base of support in Minnesota in his own right, even managing to win over support from people who consistently voted for Perpich. While he was not invincible, the chance that Democrats would realistically be able to take him down was certainly still low. He was the incumbent, and in a midterm environment expected to be positive for the Republicans, that was likely going to be more than enough to carry him over the finish line. Just like Perpich, he was well on track to win re-election.

However, as 1990 progressed, this position of strength suddenly began to decline rapidly. Metro liberals and moderates, long frustrated with Perpich’s heavy focus on rural parts of the state, would mount a strong primary challenge to him in 1990, bringing him down to just 55% of the vote against his metro opponent Mike Hatch, a former ally of the governor who got 42% of the vote off the backs of the Twin Cities metro. This left the governor weakened badly in the metro, meaning that if the Republicans played their cards right, metro anger could end up bringing him down.

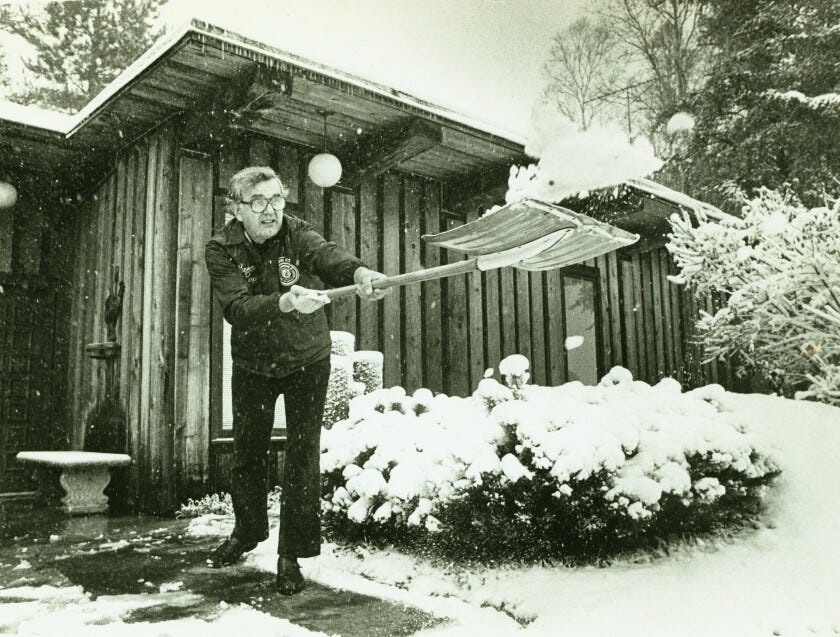

At the same time, Boschwitz was quickly beginning to look weaker and weaker. Confident of his re-election, he effectively put his campaign on autopilot, assuming that incumbency on its own would benefit him enough. He would continue to do this after his main opponent was officially nominated to be his main DFL challenger, assuming it would be yet another sacrificial lamb the DFL put up to say they had a challenger to him. Unfortunately for him, his new opponent was going to be nothing like his past two rivals. He was a real force, and he knew exactly where to hit the incumbent. That man was Paul Wellstone, a Carlton College professor and left-liberal activist from Northfield.

Initially, Paul Wellstone was a candidate absolutely no one took seriously. Not only was he going up against an established Republican incumbent, not only was he at a massive cash disadvantage, but he was also a self-described “proud liberal” during a time when the Democrats were running away from the word at record speed. In absolutely no world should he have ever been even remotely competitive. He should have lost to Boschwitz by double digits, just as every other challenger did, right?

Well, the difference between Wellstone and those past challengers is that Wellstone was an absolutely brilliant campaigner and strategist. Knowing full well that Boschwitz wasn’t taking him even remotely seriously, he sought to capitalize on that fully, playing right into Minnesotan’s growing frustrations that Boschwitz wasn’t taking his job seriously. Nowhere was this better shown off than in his most famous ad, where Wellstone would make a comedic video where he would try to get Boschwitz to debate him, but to no avail. It was an absolutely perfect ad. Not only was it funny, but it also portrayed Wellstone as a grassroots, anti-establishment fighter for all of Minnesota who was going up against an establishment politician who thought that votes should just be handed to him. For this political environment, it worked like a charm, and Wellstone very quickly began to gain on Boschwitz.

Suddenly, it looked like Perpich and Boschwitz may be in real trouble. Once thought to be solidly in the lead, they were now looking at the possibility that their races may be far more competitive than they thought. While they initially planned to be cozy, they quickly realized that wasn’t going to work. They had to at least try to win.

Unfortunately for both of the Rudy’s, even when they did that, just about everything would go wrong for them.

The Rise of the Metro Coalition

While Boschwitz was beginning to struggle more and more, it still looked like Perpich was in a strong position for re-election. Sure, he was damaged after his primary fight. But his Republican opponent Jon Grunseth was also not particularly threatening, failing to really establish a profile of his own, and was well on track to be another challenger that Perpich pushed aside. Even if metro voters weren’t thrilled with his excessive rural focus, most of them still weren’t willing to elect a conservative Republican in his place.

However, everything would completely change in October. While I won’t go into detail about Jon Grunseth’s sexual misconduct (you can read more about it here if you are interested), it was incredibly damming and disgusting, and it immediately prompted him to drop out of the race entirely on October 28th, leaving Perpich with no Republican opponent.

Suddenly, just a week before the election, a new dynamic had crashed its way into the scene: Who would be the Republican replacement? More conservative figures in the party wanted to nominate Cal Ludeman, the Republican nominee for governor against Perpich in 1986. More moderate figures wanted to nominate Arne Carlson, the State Treasurer who placed second in the 1990 GOP gubernatorial primary. This was a hot topic of debate and one that they would have to settle quickly.

This put Boschwitz in a difficult spot. Over the course of his campaign against Wellstone, he would make several different campaign fumbles, with the most notable one being when he tried to paint Paul Wellstone as a fake Jew. Statements like this would backfire harshly on Boschwitz, and it soon became clear that he was in serious danger of losing his race. He needed to do something quickly to turn this race around, and his endorsement for the new GOP gubernatorial nominee would have to play a role in doing that. So, what did he decide to do?

Rather than embrace his conservative base, he would go right into the arms of the moderate wing, giving a full endorsement to Arne Carlson. This proved to be the endorsement that put Carlson over the edge, officially making him the new challenger to Perpich. Just like in 1978, Boschwitz was making a play for moderate voters who may have been turned off by the DFL in recent years and could have potentially been turned off by Wellstone’s liberalism.

Unfortunately for him, this political play didn’t work at all. Moderate DFLers, who had previously been more receptive to voting for him in 1978, knew exactly who he was now. He was not going to be suddenly turned into a liberal Republican who led by consensus. He was going to remain a down-the-line party Republican who didn’t really care enough to talk to his own constituents. While Wellstone may have been a staunch liberal, he was a liberal willing to listen and talk to them about their concerns. He was a new, fresh option in the face of a boring incumbent who didn’t look like he cared. Ultimately, all this move did was anger conservative Republicans who wanted Boschwitz to take a harder stand for Ludeman. In an effort to win over new voters, he completely failed, and in the process, made turnout among his core base weaker than it otherwise could have been.

As all of this was happening, Rudy Perpich had also just suddenly been thrown into a race where he was at a considerable disadvantage. Just like Paul Wellstone, Arne Carlson knew exactly where to hit Perpich where it hurt. In this case, he would attack him for not caring enough about the Twin Cities metro, positioning himself as the liberal Republican candidate of the disaffected moderate metro voter. For Carlson, it worked like a charm. These voters, previously willing to give Perpich a pass in the face of more conservative opposition, were quickly ditching the long-time incumbent in the face of a liberal Republican. While Perpich still had a rural, ancestral DFL base, that was quickly becoming the only thing he had. Simply put, he needed at least some metro support to win, and he wasn’t getting it.

As Election Day came, both Boschwitz and Perpich had been reduced from their positions as strong favorites to straight-up underdogs. Once truly established incumbents, the two men of separate parties were now on track to lose to insurgent opposition. It was a truly shocking turnaround, and there was almost nothing like it anywhere else in the country.

The Ultimate Ticket Split

Despite being from different parties, both Paul Wellstone and Arne Carlson would ultimately prevail from the same coalition of people: disaffected Twin Cities metro voters.

On the one hand, these metro voters were not satisfied with Boschwitz. Feeling ignored by him and not willing to fall for his liberal Republican schtick again, they would fall right in line with Paul Wellstone, the perfect candidate to point out Boschwitz's many failings. On the other hand, Perpich’s lack of focus on the cities had finally caught up to him, as frustrated metro voters went strongly behind Arne Carlson, a man who represented himself as one of their own in a struggle to be seen by the state government again.

What ultimately came of this was a truly bizarre split coalition. Rural areas, who were highly skeptical of Wellstone’s liberalism and receptive to Perpich’s support of the region, saw themselves ticket split for Boschwitz and Perpich, both of whom put up solid margins of their own in these rural counties. Meanwhile, urban areas, who had felt ignored by Perpich and Boschwitz at once, also saw themselves ticket split, this time for Wellstone and Carlson. Ultimately, that metro coalition would be the one that prevailed, and with it, Minnesota had just experienced something of a major shakeup in representation.

Out was Perpich and Boschwitz, and in was Carlson and Wellstone.

Conclusion

There are many things one can take away from this piece. One could see that this could have been an inflection point in the history of the DFL, with the party beginning to focus on the urban and suburban communities of Minnesota, as that’s where they saw the future. Another could see this piece as an example of why you need to try in elections and never assume people are just gonna vote for you by default. Finally, one could see this as a success story for both Paul Wellstone and Arne Carlson, both of whom managed to strike at how the people were feeling at a perfect time.

Ultimately though, I think the fact that there are so many messages you can take away from this result is what makes it truly interesting. It’s an absolutely fascinating time in Minnesota when a group of disaffected voters in the Twin Cities metro decided they were tired of their politicians taking too much focus away from them. In doing so, they elected both a progressive liberal DFLer and a moderate pro-business Republican. It’s a truly confusing result at first, but upon further analysis, it’s fairly easy to connect the dots.

That’s what makes the 1990 Minnesota ticket split so interesting to me: it’s one of the strangest cases of it, but it’s also easy to understand. That’s not something you see all that often.

Please do more analysis with regards to Wellstone. I find his career extremely interesting.

why were there so many wellstone-carlson ticket spliters in the minnesota valley