Obama '12: Part Two

How battles over the budget allowed Obama to reframe the debate

On June 30th, 1989, a juvenile court jury in the state of Ohio had convicted Congressman Buz Lukens of paying an underage girl for sex, and the judge soon handed him a sentence of 180 days in jail and forced him to pay a $1,000 fine. When he decided to go against the demands of his party’s leadership and run for re-election anyway, there wasn’t much doubt about how the election would go from there. The Republican establishment would quickly settle on Tom Kindness, the 8th district’s Republican Congressman before Lukens. Not only did Kindness have near-universal name recognition among his former constituents, but his past connections with leadership also gave him a massive war chest to boot. With his only noteworthy opponent being a disgraced pedophile, Kindness’ reentry into the political scene seemed obvious to the few outsiders who even bothered to care about such a low-profile race.

A few months later, while almost no one was looking, someone decided to partake in something truly bizarre. Long after the establishment had settled on backing Kindness, a little-known State Representative named John Boehner decided to take a shot at the race. For a while, it was almost impossible to imagine this campaign amounting to anything. The 40-year-old Boehner had virtually no money to his name, nearly depleting his entire family’s bank account to fund his campaign. The Republican establishment saw his effort to be counterproductive, frequently deriding the campaign to his face behind the scenes. His attack campaign on Kindness for his poor ethics record and elite connections was largely dismissed as a relic strategy straight from the immediate aftermath of the Watergate scandal. Even his own last name seemed like a non-starter, with voters frequently mispronouncing it as boner. If this seemingly doomed campaign would leave behind any legacy at all, it would be as the strangest end to a young politician’s career in recent memory, on top of having a funny last name.

But in the end, despite all of the flaws that I just listed, Boehner would ultimately prevail over his establishment-backed opponent, defeating him with 49% of the vote to Kindness’ 32%. Since the district was overwhelmingly Republican, it had effectively solidified him as the 8th district’s Congressman-elect. It was a stunning ascension that few had expected, and Boehner would soon take his anti-establishment bona fides to the House of Representatives, as seen when he joined the Gang of Seven in early 1992 in response to some noteworthy congressional scandals. Not long after the 1992 elections, he would team up with Newt Gingrich—a fellow Republican Congressman and anti-establishment insurgent—to draft the Contract for America, the now-famous document that laid out their plans if they had won control of Congress. It proved to be a smashing success with voters, who would later deliver the GOP its first U.S. House majority since 1954. With Boehner validated in his efforts, the now-House Speaker Gingrich would reward him with a promotion to the Chair of the House Republican Conference, the fourth-highest-ranking position in the entire chamber. Just over five years after the Republican establishment had written him off, Boehner would completely usurp that very same establishment, and in the process, rebuild his party’s tattered image and grassroots base. Simply put, had the Ohioan not embraced anti-establishment politics in his very first race, it’s virtually impossible to imagine him entering the halls of Congress at all, much less becoming a key part of his party’s leadership.

Given that fact, it makes sense why on January 3rd, 2011, the day when he would finally take the Speaker’s gavel for himself, John Boehner felt somewhat peculiar. On paper, the beginning of the 112th Congress was a massive victory for him. Just two years after overseeing an election that saw his party go down to just 41% of seats, he now laid eyes on the largest gain in seats that Republicans had made in the House since 1938. The key points that the Tea Party movement ostensibly cared about, like deficit reduction and spending cuts, rang pretty to this fiscally conservative country club member. He didn’t even have any caucus dissent during that day’s speakership election, a luxury he would never enjoy in his subsequent speakership races. To a casual observer, the 2010 midterms could appear to be a vindication of Boehner’s vision for the country and his party.

Of course, the truth of it was far more complicated. Yes, Boehner’s party did win a massive mandate, and Boehner was the primary beneficiary as the party boss. It’s also true that, at least at the beginning, he had commanded relative respect with his party’s more hotheaded freshmen. But when you compare his role in the 2010 elections to his work in the 1994 elections, it’s clear why Boehner didn’t feel quite the same as he did then. In 1994, Boehner was right alongside that year’s insurgents, both in ideology and in rhetoric. Most of his attacks against then-President Bill Clinton were the same ones harbored by the party’s grassroots, from the supposed evils of Hillary Clinton’s healthcare proposal to controversy over the Whitewater scandal. The party base was increasingly anti-establishment, and they viewed Boehner as a credible ally on that issue. His direct partnership with Gingrich earned him credibility with the base that had come to love the Georgian’s passion and intensity. Throughout that year’s election cycle, Boehner had emerged as one of the prime architects of the new Republican majority, built on a strong right-wing and anti-establishment message.

By contrast, his involvement in the 2010 elections is far more distant. After the 2008 elections had left the Republican Party in ruins, the party’s base once again became enthralled in anti-establishment politics. Born out of anger over what they viewed as far-left radicalism from the White House and the Democratic Party, the grassroots started demanding that its leaders take this perceived threat more seriously and block everything that the Democrats tried to push. The grassroots opposition was especially stark when it came to proposed spending bills, arguably creating the spark needed for the emergence of the Tea Party movement. Compared to the Contract for America, the goals behind the Tea Party movement were far less defined. While it was initially formed by those concerned about the rising national debt and deficit, it soon evolved into a de facto big-tent club for those who had anything negative to say about the White House. This led to rhetoric from the Tea Party becoming increasingly ugly, from claims that the Affordable Care Act included “death panels” to doubts about whether or not America’s first black President was even American to begin with. In essence, to be beloved by this new grassroots meant that you had devoted your entire career to engaging in hyperbolic conspiracism and hysteria.

For John Boehner, the more radical elements of this movement felt completely foreign to him. He could understand the Tea Party’s diehard faith in fiscal conservatism; he had been among its strongest soldiers throughout his time in Congress. Being someone who rose into the ranks of power on the back of it, he could sympathize with their anti-establishment crusades. He could even get behind the tactic of never giving the White House any bipartisan wins, something he would later exercise when he successfully united his entire caucus in total opposition to both the 2009 stimulus package and the Affordable Care Act. But the idea that he would never work with the President, or that he would entertain insane conspiracy theories about him or his party, made absolutely no sense. After all, while his party had built a majority in 1994 partially off the back of anger directed at Bill Clinton, they would still go on to work with the President on implementing critical elements of the Contract for America, most notably when both sides negotiated the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996, better known today as Clinton’s signature welfare reform. To Boehner, if meaningful steps could be taken towards drifting the country away from aggressive spending, even if that meant cooperating with a Democrat, what exactly was the harm? Were we not sent here to address the ballooning deficit?

Ultimately, this was a disconnect that was never bridged during his first term as Speaker. Every time Boehner had expressed any interest in working with the White House, major voices on the right would chastise him as a traitor, sellout, and disgrace to the conservative cause. When he offered light concessions to the President in exchange for bigger cuts, there would be calls for him to step down from leadership altogether. This all left Boehner extremely frustrated, not only because it meant that nothing was actually getting done, but he also was smart enough to know that this chaos in his caucus was emboldening the very man he wanted to see defeated just as much as his right-wing critics did: Barack Obama.

For this part, I want to go over the budget battles John Boehner and Barack Obama found themselves involved in, the lessons they took from them, and how they each helped shape their parties’ respective outlooks ahead of the 2012 election.

Just a Golf Game

When the 112th Congress was officially sworn into office, it was difficult for Barack Obama to find any source of optimism in the event. Not only would the number of Republicans being sworn into the U.S. House be the largest since 1946, but so many of the new Republican freshman class were elected on the simple promise that they would resist his administration without any reservation. Some of these politicians even came from his own home state, such as Illinois’ 8th’s Joe Walsh, a former talk radio host who argued that Obama only got elected because he was black. Many of the fringe lunatics that could be previously ignored as irrelevant loons, such as Minnesota’s 6th’s Michele Bachmann, were now prominent enough that they could give their own State of the Union responses free from their own party’s pressure. This new Republican majority was large, in charge, and most depressingly for the President, chock-full of insane people.

It was amidst these feelings of dread that Obama would first find himself attaching to John Boehner. The speaker undoubtedly held misguided priorities, and his record in the opposition as a steadfast roadblock left the President with a poor first impression. But Boehner had also reminded Obama of the kinds of Republicans he used to work with back when he was in the Illinois State Senate: wealthy, suburban country club goers with a love for cigars and a nice glass of wine. They were always staunch fiscal conservatives, but they were also reasonable dealmakers who were willing to provide real concessions if it meant getting the job done. From this angle, Obama began to make strides towards the new Speaker, which started with him making an offer, something he knew that he could get behind: golf.

Playing together in a 2 vs. 2 match against Vice President Joe Biden and Ohio Governor John Kasich, Obama and Boehner worked well as a competitive duo, winning the game on the 18th hole and earning themselves $2 each. Afterwards, the men would sit down inside the nearby patio and enjoy some cold drinks while coverage of the U.S. Open played in the background. While much of the summit’s conversations were simple pleasantries between the four men, Obama and Boehner would also spend some of the time discussing what they wanted out of deficit reduction. With the debt ceiling cap looming and demands for action on the budget increasing, Obama saw it as a prime opportunity to work out a deal with Boehner that tackled this issue once and for all. Boehner, long eager to take on one of his favorite issues, happily accepted the gesture and took up the President on an offer to work out the finer details at the White House a few days later.

Well aware that his base would pan this move towards the President, Boehner opted to meet with Obama in secret. He didn’t even disclose the news to the House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, mainly out of fear that his uncompromising posture in public negotiations with Joe Biden would muddy the process further. On his part, Obama found negotiating the deal to be intensely invigorating, canceling fundraisers left and right to have more talks with Boehner. Eventually, the two men would each settle on their dramatic concessions, both of which could have done serious damage to their standings in their respective parties. On Obama’s end, he was willing to offer austere entitlement reforms, including cuts to Social Security and raising Medicare’s eligibility from 65 to 67 years. In exchange, Boehner would offer his support for tax increases on the richest Americans, even including the closing of loopholes beloved by many wealthy Republican donors. All in all, the proposals likely would have saved around 4 trillion dollars over a decade, a sizable sum that both parties could have taken as a win for their side. Entitled the Grand Bargain by its advocates, this package represented the most serious bipartisan attempt at addressing the growing debt in modern history.

Soon after this framework was agreed upon, hopes for getting it passed into law would be quickly derailed. It would start just days later when Biden unintentionally revealed the secret talks to Cantor, forcing Boehner to include his more bombastic #2 in discussions with Obama. This would immediately make progress on the issue slow down to a crawl, with Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid later stating that Cantor “shouldn’t even be at the table”. Not long after that, six Senators from the bipartisan Gang of Six would reveal their own plan to address the deficit. While this deal would save around 300 billion dollars less over a decade than the Grand Bargain, a far higher percentage of the cost savings would be from new tax revenue. Sensing an opportunity to snatch a far better deal, Obama would approach Boehner and demand additional tax increases in the Grand Bargain. Desperate to get his new pet project done, Boehner considered taking him up on the demand, even trying to convince Cantor to jump on board. Already feeling screwed by his Speaker over his past secrecy, Cantor quickly shot down Boehner’s offer and offered him an ultimatum: Pull out of the deal, or deal with a full-on floor revolt. Not wanting to end his career on such a sad whimper, Boehner would relent to the demands of his right-wing flank and publicly oppose the deal. And with that, the last great hope for centrist deficit hawks was dead in the water.

For the two men involved in the creation of the increasingly derided Grand Bargain, the political costs would rear their ugly heads. John Boehner was not only more distrusted than ever with the Tea Party caucus, but the snubbing of his aggressive number #2 left his relationship with him and others in Republican leadership in permanently shaky ground. For the rest of his first term, Boehner was not only incentivized to play the same kind of full-throated oppositional role that the Tea Party had always wanted him to, but the security of his new job had practically depended on his doing just that. There would be no more proposed tax increases, closed loopholes, or additional regulations. In the eyes of the Tea Party, cooperation with the far-left socialists in the Obama White House was not what the American people voted for. And given the ferocity of the new Representatives that Republican voters had sent into Boehner’s caucus, it wasn’t unreasonable for him to assume that they were right.

As for Barack Obama, he would be forced to spend the next few weeks enduring a painful humiliation ritual. Just a few days before the debt ceiling would be reached, Joe Biden would successfully strike up a deal with Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. Not only was this no Grand Bargain, but it also included around 1.2 trillion dollars in spending cuts with absolutely no revenue increases. A financial calamity had been avoided, but it had involved a liberal President being forced to sign austerity cuts during a period of economic slowdown. This understandably angered the Democratic Party base, with Paul Krugman even describing the deal as taking America “down the road to banana-republic status”. Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic House leader who had voted for the bill, couldn’t bring herself to spin the reality of the bill, calling it a “Satan sandwich with Satan fries on the side”. Talks of a primary challenge to his left were more pervasive than ever, with Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders even seriously considering the idea before being shot down by Harry Reid. In the first poll conducted after the deal was finalized, Gallup found Obama’s approval rating slipped to a record low of just 40%. In the end, the only thing Obama got out of this long struggle was just a golf game.

More so than anything else, this fiasco reinforced a perception of the President that had come to haunt his first few years in office: he was weak. If he was going to fix his image ahead of the 2012 elections, he was going to have to start playing hardball with the Republicans and show the nation that he had the people’s economic interest at heart despite Republican pressure. It wasn’t something he initially felt he could pull off; despite his 2008 campaign containing many populist elements, the President had never really envisioned himself as one. Additionally, as stated in the previous article, Americans aren’t quick to blame economic problems on the people outside of power. But just as his leadership in the Bin Laden raid and Iraq War withdrawal helped reinforce his capabilities in dealing with foreign policy, a real pivot on strategy with the economy could help Americans regain the trust they had lost in him. While Boehner was taught not to cross his right-wing base, Obama was taught that it was necessary to flex his authority, both rhetorically and legislatively.

(Don’t) Pass This Jobs Plan

With that painful lesson now taken to heart, Barack Obama would spend the rest of August getting to work on rebuilding his vision for the economy. With his re-election campaign having already been in full swing for several months, Obama and his team quickly came to encounter a pervasive problem: People just didn’t know what he was selling. For as much time as Obama had spent trying to craft deals with Boehner behind the scenes, he wasn’t doing much of anything to convey his side to the public. As a result, when Obama would eventually conclude the debt ceiling saga by signing spending cuts with bipartisan support, it was the worst of both worlds politically. Voters inside his base were furious over their own services getting cut, and those outside of it didn’t care about it being bipartisan. When Obama would get on stage and complain about Republicans not working with him on the Grand Bargain, it was seen less as him being the one grownup in the room, and more as continued whining from a well-meaning but inexcusably ineffective commander-in-chief. Appeals to Republicans to stick to their word weren’t going to work; Obama needed to lay out his own vision and fight for it passionately. Essentially, he would have to fight on his own terms.

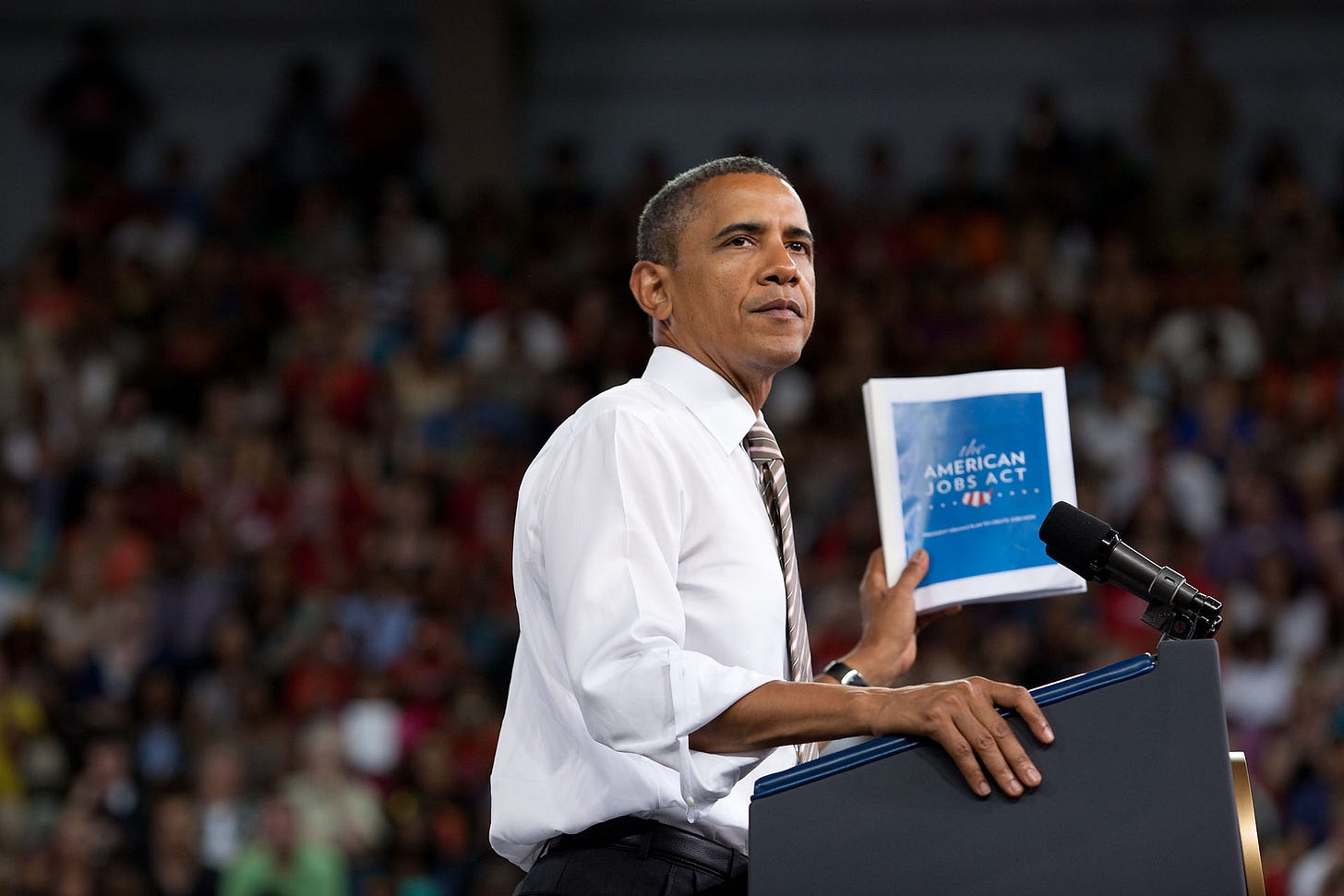

On September 8th, 2011, Obama would begin the process of doing just that. Delivering an address to a joint session of Congress, the President would introduce the American Jobs Act, a series of different bills that all made their own critical investments, each intended to reinvigorate the U.S. economy. From the 49 billion dollars dedicated to strengthening unemployment benefits, the 35 billion meant to protect the job security of teachers and law enforcement, to the 10 billion for the creation of a bank meant to encourage public and private investment in infrastructure repairs, the American Jobs Act effectively served as the second part of Obama’s first economic stimulus package in 2009.

Most importantly, however, there was not a single mention of entitlement cuts found anywhere in the bill. Yep, that’s right. In a time when the American people were supposedly hungry for spending cuts, Obama was proudly proposing even more spending.

Some observers found this confusing. After all, the very fact that the President was closing the door to even a single cut in the bill instantly made this bill a non-starter to Boehner and the entire GOP caucus, both of whom would be essential to passing it. But in choosing to craft the bill in this fashion, it showed two very important evolutions in the President’s thinking. The first was that he was once again returning to a more Keynesian approach to economic slowdowns, delighting the liberals in his base who were previously angered over his flirting with austerity. The second was that he was taking a fundamentally different, much more savvy approach with Boehner and the right this time around. Despite his insistence on Congress “passing this bill right away”, Obama knew full well that he did not have anywhere near enough votes to pass the American Jobs Act. But the purpose of the bill wasn’t to pass it in full. Rather, he was going to use the bill as a front for his public rehabilitation tour, wherein he would slam the Republicans for their inaction while casting himself as a fighter for basic common sense.

For the first time in years, Obama was taking his stance into the court of public opinion.

Referendum vs. Choice

Dubbed the “Jobs Act Tour”, Barack Obama’s public relations pursuit would begin just a day after his address to Congress in Richmond, Virginia, which would be a crucial city for him to turn out if he wanted to win this valuable swing state. It was here, in the Robins Center Arena near the eve of autumn, that the first hints of Obama’s strategy for the 2012 election can be spotted.

It begins with a basic acknowledgement of the reality that Americans were facing; the economy was lousy, there weren’t enough opportunities for young people to get employment, and people were right to be frustrated about it. This part is important because it sets up Obama not as an out-of-touch bureaucrat unaware of the reality on the ground, but instead as someone in tune with the reasons why economic optimism had long been running dry. From that premise, Obama lays out each part of the American Jobs Act and goes to great lengths to give each one a populist spin. On his plan to invest in infrastructure, Obama takes the protectionist angle, arguing that it is a necessity to ensure construction jobs aren’t outsourced to China. For his spending on teachers, he describes it as the main solution to continued teacher layoffs, and by extension, the solution to increasing problems in children’s education. Regarding his extension of unemployment benefits, he describes it as necessary to keep the economy afloat.

All of this would have been impressive enough on its own, but the topic of deficit reduction is where the President would truly strike gold. Instead of framing it as an issue of bipartisanship, where entitlement cuts are just an unfortunate part of the equation, he flips the discussion on its head and presents the public with a choice: Do you want to reduce the deficit by raising taxes on the wealthy and big corporations, or do you want to cut social services and repeal tax credits for small businesses?

It was absolutely brilliant political craftsmanship. Not only did the President successfully present a clear vision that voters could get behind, but he did so while avoiding making the question of the election a referendum on his performance. Everyone on his team, including the President himself, knew that they could not win the issue if they fought it like a referendum. They weren’t going to be able to explain away people’s economic struggles by meekly pointing to data or waving away responsibility. The President had to accept the reality around him, while also making clear what he was going to do, as well as what obstacles stood in the way. In pulling this off successfully, he was finally able to get more people to come around to what he had been thinking from the start: He was the grown-up in the room, and the Republicans were the children meant to protect the wealthy, even if that came at the expense of the middle class. It was their choice as to which one they preferred.

Over the course of the next few months, Obama would take this stump speech throughout the rest of the country. Most Republicans were initially dismissive, seeing how most polls did not initially see a spike in Obama’s approval rating. But as the tour went on and Obama hammered down on an extension of payroll tax cuts, voters became more receptive to the President’s message. By the time November came around, Gallup had Obama’s approval numbers rising to 43%, with his net approval compared to August going up by 7 points. Furthermore, coverage of the Republican Congress’s rejection of the plan only grew more negative, with the normally GOP-friendly Wall Street Journal describing Boehner’s and McConnell’s opposition as a giveaway to Obama’s re-election chances. Eventually, Boehner and other Republican leaders realized that ignoring the problem was politically unsustainable, but since they knew they would be blamed for any payroll tax increase, Obama was allowed to negotiate the deal on his own terms. What followed were two back-to-back wins for the President: first in the form of a temporary two-month payroll tax cut that was signed the night before Christmas Eve of 2011, and second in the form of the Middle Class Tax Relief and Job Creation Act on February 17th of 2012, which made those cuts last throughout the rest of the year.

With the legislative successes reinforcing his leadership and economically populist qualities, alongside fulfilling his promise on Iraq War withdrawal, Obama’s fortunes had finally begun to bear fruit in the polls. The first Gallup survey for March of 2012 gave the President an approval rating of 48% and a net approval of +4, his best numbers since the Bin Laden raids. Nate Silver, previously skeptical of the President’s chances for re-election in November of 2011, now believed in February that Obama was the clear favorite, noting how his new populist approach was a strong match for critical swing states like Ohio, Iowa, North Carolina, and Wisconsin. Despite alienating many of his wealthier backers with his populism, Obama was still able to consistently pull stronger fundraising numbers relative to his opponents. Considering that he was at risk of being challenged by his own party just a few months prior, the 44th President had to have felt pretty good about the way the tides had been turning.

With that being said, he was not in the clear yet. The effort to rebuild his economic image had thus far gone smoothly, but that didn’t mean that it couldn’t get thrown off course. Beyond the fact that it was a real possibility that the economy could have just slumped further into stagnation for the rest of 2012, it was also apparent that the Republicans were not going to let him suddenly start playing the game by his own rules with no resistance. After all, it wasn’t the Republicans that presided over an unemployment rate that perpetually sat above 8%. It wasn’t Republicans who couldn’t find a way to lower gas prices. It wasn’t Republicans who failed to live up to the promise of “hope and change.” Simply put, Republican strategists had come to understand this fact just as well as Obama had: If the election is a referendum on the President’s performance, he will lose. And since their goal is to defeat Obama, they were going to do whatever it took to make it a referendum election.

For a while, it wasn’t entirely clear which Republican would be the one to take on this mantle of responsibility. Primary polls fluctuated constantly, with five candidates each having their turn at being the Republican frontrunner. Each of them had their own strengths the Obama team had to work around, as well as weaknesses they could exploit. There was Texas Governor Rick Perry, a right-wing kool-aid drinker who had a lot of charisma, but not the intelligence necessary to remember his own plans. There was former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, a longtime conservative champion with a history of questionable marital issues. There was Rick Santorum, a pseudo-populist social conservative who had managed to have real pull with some blue-collar workers, but also had the stain of losing by over 17 points in his own home state. Even Herman Cain, a former pizza CEO with a laughably simplistic tax plan, managed to steal the frontrunner spot before having to drop out over allegations of sexual harassment. As late as March, the Obama team still wasn’t entirely sure who they would have to slog against for the next several months.

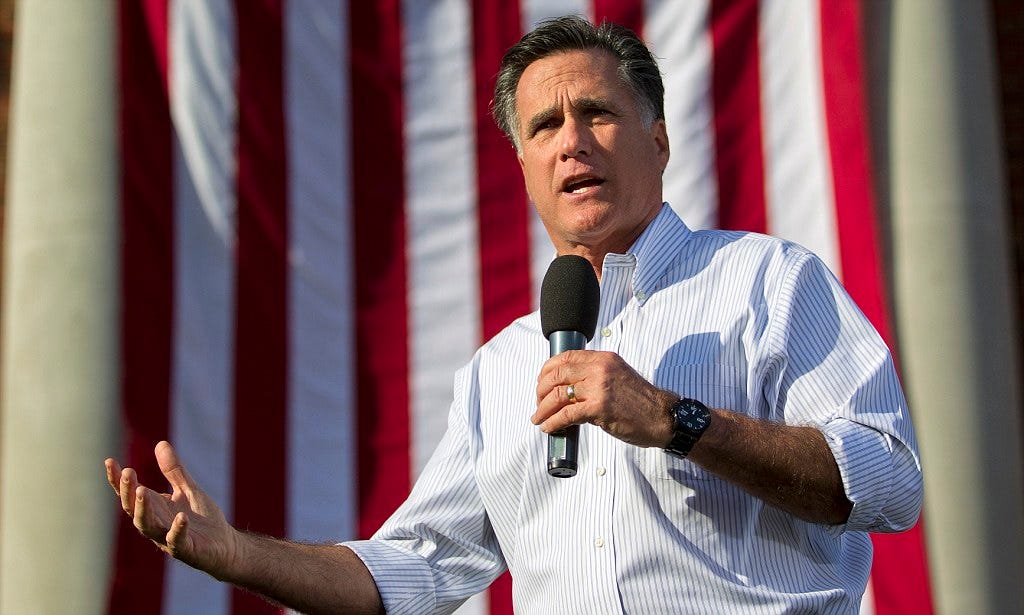

But by the time the process concluded, the Republicans had finally settled on a guy who, at least on paper, was supremely qualified to take on this role. He had a well-established history as a successful businessman, even saving the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics from financial ruin. He had experience winning and governing as a Republican in a deep blue state. He had galvanized upon anti-immigration policies that had become very popular among the blue-collar workers whom the Obama campaign needed to win.

Theoretically, everything about former Massachusetts Governor Willard Mitt Romney should have made him the perfect candidate to become Mr. Fix-It, harness economic discontent, and turn this election into the referendum that Republican strategists were dying for.

But over the course of the next few months, the Obama team would do everything they could to make sure this would never, ever happen.

Stay Tuned for Part Three!