Obama '12: Part One

The story of the greatest presidential campaign in modern American history

On November 2nd, 2010, the United States appeared to be undergoing a seismic shift toward a revamped conservative consensus.

Just two years after being swept out of power in a clear landslide, the Republican Party would roar back in a way that even the party’s biggest advocates couldn’t ever dream of. Not only did the GOP flip the U.S. House after four years of Democratic control, but their net gain of 63 seats was the largest that the party had seen in over 70 years. Democratic state control was shattered all across the country, including in solidly blue states like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. While the U.S. Senate would remain under Democratic control, their near-supermajority of 59 seats was cut down to 53, putting their control of the chamber on borrowed time.

Wave elections in favor of the opposition party were nothing new by 2010, but this was far more than just a simple check on power against the Democrats. Not only would hundreds of Democrats lose their jobs, including several who had previously been considered deeply entrenched in their positions, but their replacements would often be the sons and daughters of the unapologetically conservative Tea Party movement, whose core principle was a complete rejection of compromise with the Democratic Party. They didn’t want to limit spending; they wanted to kill it. They didn’t want to fix the Affordable Care Act; they wanted to repeal it. They didn’t want to unite around centrist judges; they wanted to block any judge not sufficiently committed to moral conservatism. The message of the 2010 election, at least in the eyes of a sufficient chunk of the American population, was a simple one: Block the Democrats at all costs, no questions asked.

As election night wore on and this new political reality set in, the White House was consumed by despair. This outcome wasn’t much of a surprise to them; the polls had been pointing in the direction of a Republican wave for months by that point. But the visual of a wave so decisive was still hard to fully take in, and it left advisors with little sense of where to go next. Some would even leave their jobs altogether, including Rahm Emanuel and David Axelrod, both of whom had been among the most important members of the team since they first entered the White House. However, amid all this turmoil, the man at the center of this backlash found himself returning to a sense of political humility.

Up to this point, President Barack Obama’s career had been nothing short of astounding. First elected to the Illinois State Senate in 1996, Obama would begin climbing the ranks in a fashion no one in the Democratic Party had been capable of since the days of Harry Truman. Quickly gaining a reputation as a charismatic talent, he would use this momentum to breeze his way into the U.S. Senate in 2004, crushing his Democratic and Republican opponents along the way. Less than three years later, he would announce his candidacy for the presidency on the same steps where Abraham Lincoln delivered his famous “House Divided” speech, a less than subtle acknowledgment of the historic nature of his campaign. From here, his ascension to the top would overcome obstacles almost no one thought possible, dismantling the previously unchallenged Hillary Clinton machine and obliterating John McCain’s bipartisan maverick appeal with just a single year. The road that led him to this position was unprecedented in the modern age, and it left people forgetting a critical moment in the President’s career: his only loss.

In September of 1999, believing in himself just a bit too hard, 38-year-old State Senator Barack Obama announced his intention to primary against incumbent Democratic Congressman Bobby Rush in Illinois’ 1st congressional district. This was something many of his closest friends warned him against attempting, and as the campaign progressed, all of their fears would be realized despite Obama’s dismissals. He was never able to make a convincing case in favor of ditching Rush, bizarrely trying to argue that the popular 53-year-old Congressman elected just eight years prior was a symbol of the past. Meanwhile, he had very little to offer of his own, allowing his opponents to paint him as an out-of-touch elitist with little resistance. All of this culminated in a massive loss to Rush just a few months later, which had the very real potential of sending his political career into a death spiral. While he would manage to turn it around in a remarkably spectacular way, it stood out as the one moment throughout the 2000s that the Chicago-based superstar was ever truly humbled.

Fast-forwarding to 2010, sitting right in front of a TV that projected his party taking massive losses, Obama was forced to come back down to Earth once again. While he wasn’t on the ballot this time around, it was clear that the anger that was widespread throughout the country was directed at him, first and foremost. They despised the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare, his signature achievement that he had spent his entire first year pushing through. Despite his constant attempts to reach across the aisle, he was increasingly being portrayed as a far-left radical by his opponents. The hope and change he promised to deliver began to look like a cruel joke, with unemployment still hovering at just under 10% despite his signature 2009 economic stimulus and other important pieces of economic reform. The stardom that had swept him and his party into power in 2008 was long gone, and he was now forced to work with a new Republican Congress that was elected to stop him at every possible opportunity. For the first time, results came in that showed the President a very clear message: re-election won’t come easily.

The next day, Obama was forced to come out of his bubble, describing the result as nothing less than a “shellacking”. While he stopped short of criticizing his own policies, he acknowledged that many of his supporters were deeply disappointed in a way they never had been before. It was a humiliating speech, and to many observers, it marked the beginning of a long story that would eventually end in the President’s political career in irrecoverable tatters. Not only were the tides against Obama similar to those against one-term presidents, but all of it came alongside his new image as a false political messiah. The promise of President Barack Obama was unlike anything seen in generations, and the evaporation of that image had the 44th President experience a fall from grace not seen in decades. Not even the Democratic primary looked like a sure bet anymore, with Independent Senator and Obama ally Bernie Sanders stating that a progressive challenge to the President would “enliven the debate”. Not since Jimmy Carter had the path for a second term looked more bleak for a Democratic President, and political obituaries for his tenure had already begun to be written.

However, just as the loss to Bobby Rush had paved the way for his rise to the top, the shellacking Obama took in the 2010 midterms would prove to be the spark needed for Obama to reclaim his image. Over the next two years, the battle-scarred President would run a campaign operation unparalleled in modern American history. Presiding as an incumbent over a poor economy, a mixed foreign policy record, and increasing populist anger directed towards his administration, Barack Obama managed to define his re-election campaign on his terms, turning seemingly every single perceived liability into a valuable asset. He would rebrand himself AND his opponent to his liking to the extent that it was sometimes difficult to remember that he wasn’t challenging an incumbent. Despite his failure to deliver on hope and change, he would manage to win back almost all of his base from 2008 within just a year and secure the mantle of change one last time. His team would commit to widespread outreach into growing communities of color in the Sun Belt while keeping their support among working-class whites in the Rust Belt largely intact. No matter the problem, the Obama campaign always had a working answer, serving as yet another example of the 51-year-old’s political astuteness.

The result of this was a decisive re-election, whose relatively close result underscores just how legendary the path to get to this point had been. Theoretically, no one should have been able to pull off what Barack Obama did. No one should have been able to get away with presiding over an unemployment rate of 7.7% and rising prices. No one should have been able to recover their political image after a historic rebuke to their government just two years prior. No one should have been able to run a change campaign after four years of being relatively meek. None of this should have happened, but Barack Obama made it a reality. In doing so, the newly crowned two-term President would end his political campaign career on a gargantuan high note, cementing his place in history as the face of the best-run political campaign in modern American history.

This series is about how he managed to pull this off, covering everything in between his initial announcement to Election Night 2012 itself. As the Democratic Party currently struggles to establish itself following its 2024 election defeat, it’s worth looking back at the most successful Democratic operation in the 21st century to remember that political ineffectiveness from the Democratic Party is by no means inevitable. Even under theoretically terrible circumstances, the Democrats are perfectly capable of running a spirited effort that can defy the odds. Obama may be an exceptional talent in some respects, but that doesn’t mean his campaign didn’t carry lessons that we can take to heart now. The playbook offered by this campaign has been ignored for far too long, so I’d like to shine some light on it.

The State of the Union

On January 25th, 2011, Barack Obama headed over to the United States Capitol to deliver his yearly State of the Union address. This would be the first time he’d be addressing a Republican-controlled House of Representatives since becoming President, and there was a degree of uncertainty in the air. Most of the freshmen in that room had been elected to serve as staunch foes to the President, and if Representative Joe Wilson’s outburst two years prior had proven anything, it’s that the Republican base was big fans of performative acts of disobedience. Before the speech, it would have been fair to expect these recruits to pull off something similar for their shot at fame in Tea Party circles.

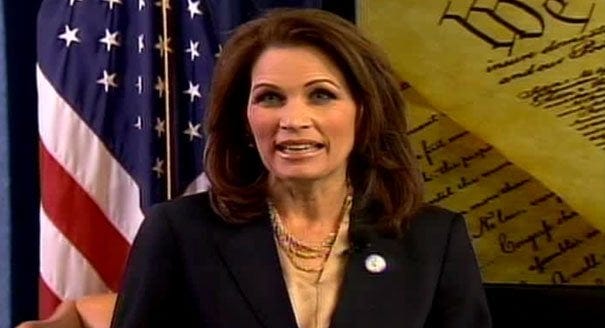

However, just two days before the speech, the Republican Party found itself in a panic when Congresswoman Michele Bachmann, a darling of the Tea Party movement, announced that she would be delivering her response to the State of the Union separate from the official Republican response. Many pundits saw this move as a very unusual display of disunity, especially for a party that had just won a massive victory just a few months prior. Republican leadership disdained Bachmann’s gesture, even forbidding her access to the GOP Capitol Hill Club where she had originally intended to deliver her response. After just twenty days of being in charge, there was a brand new, large crack in this new Republican majority, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last to come throughout the tumultuous 112th Congress. Despite Bachmann’s insistence otherwise, the message from this was still clear: The Tea Party’s target wasn’t just the Democrats, but also their party establishment.

All of this left the President in an awkward position. Obama was certainly familiar with how to campaign against Republicans; he wouldn’t have been sitting in the Oval Office if he hadn’t. He even had prior experience running against a crank in the form of Alan Keyes, his Republican opponent in the 2004 U.S. Senate election in Illinois. But never before had he dealt with a group as large and as aggressive as this new freshman class. The fact that they were capable of delivering their own State of the Union response was just the clearest example yet to prove that these guys couldn’t be safely ignored and muzzled by their leadership. They were going to step on whatever toes were necessary to make their voices heard, including their own party’s Speaker and his establishment allies. It was a tricky situation for the politically wounded President to navigate, and while he wouldn’t officially announce his re-election campaign yet, it was one of the first giveaways as to how Obama would conduct his effort.

For the most part, the speech itself didn’t feature anything out of the ordinary. After an acknowledgment of the recent assassination attempt against Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, Obama’s speech largely consisted of bipartisan appeals he had expressed willingness towards in prior statements, such as lowering the corporate tax rate and tort reform. It was the exact kind of speech you would expect to be delivered by an incumbent President in the aftermath of a repudiation midterm, and while it received positive reviews and went on without a hitch, it also didn’t stick around in most people’s minds.

Ultimately, Obama’s address was not where the interesting story of the night lay. It also wasn’t the official Republican response by Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan, whose measured response was similarly unmemorable and uneventful. Rather, Bachmann’s speech would receive the most attention, and it wasn’t exactly pretty. The low production value was observed the second the speech began, with the first visual being Bachmann not making eye contact with the camera, a problem that would persist for the entire speech. The camera crew was not prepared ahead of time to zoom out for Bachmann’s clip-art visuals, leaving just the corner of the image for several awkward seconds until they could readjust. While she didn’t come off as extreme as her past statements may have suggested she would, her fast-talking and passionate appeals to American exceptionalism came off as bizarre gestures in a speech already plagued by peculiarity.

Despite hitting on many of the same points as the Tea Party, the reviews of Bachmann’s speech were generally negative. Democrats criticized it for relying on extreme rhetoric against the President, which came off as particularly distasteful just seventeen days after the mass shooting that nearly killed Gabby Giffords. The Republican establishment saw it as an unhelpful diversion that made their party look incompetent and radical, two liabilities that could have doomed them ahead of the 2012 election. Others made fun of the apparent lack of preparedness on display, with Saturday Night Live even releasing a parody of this speech to get in on the fun. While getting the spotlight is usually a positive opportunity to expand outreach, it can go south very quickly if the orator isn’t ready. In the end, the 3rd-term Minnesotan Congresswoman could not build off the post-election momentum, making her wing of the party look unappealing and loony.

In retrospect, this muddled response was among the earliest signs of a problem that would develop into a strong talking point by the Obama campaign the following year: Republican incompetence. Despite being provided a historic mandate in the lower chamber, House Republicans were bogged down in internal strife over the direction to take the party, leaving little sense of a united front ahead of their efforts in the 2012 election. This allowed the Obama campaign to define them instead, applying the worst perceptions that people had about the Republican establishment AND the Tea Party in one. In doing this, he was able to kill two birds with one stone, haunting his various Republican prospects' hopes later down the line and establishing himself as the early frontrunner.

Solving Iraq (For The Time Being)

For most of Obama’s first two years, foreign policy had largely fallen to the sidelines. While he had been elected in 2008 on a promise to rebuild America’s image, that commitment was partially held off amid a global economic crisis and grueling healthcare debate. Given the historic size of the Democratic majority he was elected with, it just made more sense for him and his team to prioritize their domestic agenda first.

However, once the 112th Congress made it clear that it had no interest in working with the White House, foreign policy suddenly emerged as one of the last areas where the President could still have meaningful sway. With his signature achievement signed into law and the effects of his economic policies slowly beginning to take shape, Obama decided to direct his focus towards implementing his foreign policy agenda, and from a political perspective, there was one clear issue to take care of.

Apart from the Great Recession of 2008, no other issue had been a bigger factor in Obama’s rise to the presidency than the U.S. involvement in the Iraq War. First started in 2003 under the guise that then-Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction, the Iraq War was initially extremely popular with the public and scored bipartisan support in both Houses of Congress. With American fears still high after the September 11th attacks, they were more than happy to rally behind the effort that they saw as bringing stability to the world, or as President George W. Bush described it, “a war on terror”. Mere days after the Iraq War had commenced, Bush’s approval rating in Gallup would shoot up to 71%.

However, there was always a critical error underlying this entire mission. While it was true that Saddam Hussein was a monster who was complicit in mass genocide and oppression, it was also true that he had been the only real stabilizing force in the country by 2003. Many in the Bush administration were well aware of this, including the administration’s figures who had also served with Bush’s father in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, like Secretary of State Colin Powell and Vice President Dick Cheney. Despite being in the theoretically perfect position to do so, Bush Sr., Cheney, and Powell all agreed to hold off on toppling Saddam Hussein under fears that it would further destabilize the country and the Middle East as a whole. Contrary to what conservatives said at the time, this conclusion was hardly some critique limited to anti-war leftists in France and Germany; it was essentially just geopolitical common sense. Any justification for toppling him was always going to require a comprehensive plan to fill the vacuum, and if no such person could be provided, the reasons behind an attack should have been ironclad to justify the fallout that would ensue.

In the end, this problem was never even considered by the Bush administration, including by skeptics from within. After Bush initially declared the toppling of Saddam Hussein a victory within weeks under a now-infamous Mission Accomplished banner, the next five years of quagmire that followed would completely unravel him and his party. Not only were the promises of stability following the Ba’athist deposition proven to be a fantasy, but the Bush administration’s previous justification—Saddam Hussein’s possession of weapons of mass destruction—was exposed to be a total lie. By the time the 2004 election season had rolled around, Bush’s approval ratings had officially sunk into the negatives for the very first time, forcing him to weaponize homophobia and fearmongering to secure his second term. This re-election mandate would only make the situation worse for Bush in the long run, as his handling of the war became increasingly disastrous and indefensible. His approval ratings only seemed to slip further down, and demands for an end to the war became the majority consensus among the public. With Democrats securing both Houses of Congress on an anti-war platform in the 2006 midterms, the nation looked towards a leader who had the credibility and judgment necessary to bring this dark period to an end.

Up until the last few months of the 2008 campaign, this had been the main appeal behind Barack Obama’s candidacy. While Hillary Clinton had long been assumed to be the Democratic frontrunner and had even spoken favorably towards eventual withdrawal, her vote to authorize Bush’s actions in Iraq back in 2002 would leave serious questions about her judgment and trustworthiness. By comparison, Obama’s opposition dating back to the war’s start permitted him to strike a strong comparison between himself and Clinton, and by extension, earn the trust of voters as a serious agent of change. This soon allowed him to take the frontrunner status away from Clinton and carry over all of these same talking points against John McCain, someone who had also voted for the war. Despite the economy taking center stage by Election Day 2008, exit polls still showed that 10% of voters who described Iraq as their biggest concern backed Obama by a 59%-39% margin. As such, any successful re-election would likely have to coincide with fulfilling his promise on Iraq to the public.

Of course, going through with this was always easier said than done. While ending the U.S. involvement in Iraq was still the obvious solution by this point, it wasn’t entirely clear if the Obama administration would be able to do so while still keeping the current government stable. Withdrawal was popular among the public, but the image of a lost war would have also had dire political consequences for the President, so a balancing act would have had to be made. As domestic policy took up most of his time and media attention during his first two years, his administration also began the withdrawal of combat troops from Iraq, which would be complete on August 19th, 2010. Describing this new phase as “Operation New Dawn”, the role of the U.S. presence was now to serve as a supporting role for the Iraqi army and help secure their hold over the country before the final withdrawal scheduled for December of 2011.

In retrospect, this stage of the process did not go according to plan in the long term. While the U.S. Army could spend as much time as it wanted attempting to train Iraqi soldiers, that was never going to be enough to fix the lack of morale present among them. The new government they were fighting for was not only a corrupt kleptocracy, but it was also dysfunctional and had little ability to exercise authority. Any attempt at being caretakers for the Iraqi state would have to take a lot more time and force than the Obama administration employed, and since they lacked the personal will and political capital necessary to do this, they had to make do with the time available to them. From that perspective, it’s no surprise that after the final withdrawal was complete on December 18th of 2011, the government would fall back into turmoil just a few years later and force the administration back into the country.

But since the worst effects of that turmoil did not crop up until his second term, Obama was able to successfully reap the political benefits that came from withdrawal. While his Republican rivals would criticize him for the hasty nature of the operation, the lack of a withdrawal plan of their own, combined with their concerns about a fast withdrawal not yet becoming clear, made their argument look confusing and out of touch with the public. Not only did 75% of Americans approve of bringing the troops home, but 60% continued to do so even if the Iraqi government was unable to keep a lid on violence. Bipartisan support to that extent had become increasingly rare since the start of Obama’s term, so the fact that he was able to get it just a year before the election was extraordinary by itself.

This latest political win would end up giving the President two important assets ahead of the election. The first was that it served as an example that the change he promised was translating into tangible action, which would be especially important as Americans had been increasingly disappointed in his presidency. The second was that it helped further contribute to his status as a competent executive. By avoiding the worst effects of withdrawal and sticking to his plan without much reservation, it made Obama looked like a competent statesman who had the clear vision and guidance necessary to lead America on the world stage. By comparison, the Republicans’ confusing and wishy washy criticisms of his withdrawal policy made them look rudderless, allowing Obama to once again define the narrative on his own terms. While the salience of the Iraq War to voters had dropped far lower than in 2004 or 2008, it was one of many foreign policy decisions he made throughout the year that helped him rebuild his image.

“It’s A Go”

On October 29th, 2004, the Qatari-owned news network Al Jazeera released an 18-minute video filmed by Osama Bin Laden, the prime culprit behind the 9/11 attacks. In the video, he confirms his role in carrying out the attacks for the very first time, criticizes the Bush administration’s response to the attacks, and expresses his intent to attack the United States again. The motivation of the clip is not officially known, but the language and timing could both be deduced as an intention to boost George W. Bush’s odds of victory in the 2004 election. Four days later, Bush would narrowly secure a second term, with some polls suggesting that the tape very well could have helped the President get over the finish line.

I mention this story because it serves as an important example of the extent to which Osama Bin Laden haunted the American public and government. With the 9/11 attacks still fresh in the minds of the population, the government’s inability to capture or kill Bin Laden left people paranoid to such a level that just his words alone could have potentially swung an entire presidential election. And with Bush ultimately failing to reap the political benefits that came with eliminating Bin Laden, it theoretically left Obama with the opportunity to score some political goodwill of his own.

For a while, it wasn’t clear that he would have much more success than his predecessor on this front. Not only had Bin Laden had plenty of time to encrypt his location from U.S. and international authorities, but the collapsing economy and costly battles over healthcare reform in his first two years meant that Obama had little time to concern himself with foreign policy matters. It was by no means ignored entirely; Obama would consistently reaffirm catching Bin Laden as his top foreign policy priority. But with the likelihood of his party maintaining its overwhelming Senate and House majorities dwindling, Obama opted to prioritize his legislative wins for the time being, leaving the Bin Laden case cold for the foreseeable future.

However, while Obama and Democratic Congressional leaders engaged in endless negotiation over healthcare and Wall Street reform, the seeds were slowly being planted for an eventual takedown of the Al-Qaeda leader. In July of 2010, the National Security Agency (NSA) successfully monitored calls from Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti, one of Bin Laden’s most trusted associates, who was driving near the northern Pakistani town of Peshawar. This soon led U.S. intel to a massive compound in Abbottabad, whose size indicated that it was designed to protect a high-value target. Secret monitoring from the sky would soon begin, which only added to the case that the administration was slowly crafting. By the time working for legislative policy became impractical in early 2011, Obama was left with this new lead to consider.

When everything was said and done, it was the best lead the State Department had on Bin Laden’s whereabouts since he fled to the Afghan Tora Bora mountains in late 2001. However, that did not mean that any action taken against it wasn’t still extraordinarily risky. What evidence was available was striking, but what was equally striking was what didn’t exist. No photos of Bin Laden or his family at the compound were ever produced, leaving them with only what they described as “circumstantial evidence.” The two most effective means of taking him out—massive bombings and a helicopter raid—both had serious logistical problems that could have potentially thrown the entire operation into jeopardy. Not only was there no guarantee that Bin Laden would be found, but the consequences of getting it wrong were catastrophic in every respect. In the event of a failed bombing, the Pakistani government would be understandably furious at the death of innocent civilians via collateral damage, and it would give Bin Laden an excellent rhetorical recruiting tool for Al-Qaeda. If the helicopter raid failed, the U.S. soldiers would be thrown into immediate danger for no reason. In both cases, the public would deride the President for his failed leadership and incompetence, sending his already-slipping approval ratings down even further just as he plans to announce his re-election campaign. While success would be a massive foreign policy victory, a failure on this scale could have sent the Obama 2012 campaign to an early grave.

Some in the administration did not want to take this risk. Vice President Joe Biden emerged as one of the lead skeptics, arguing to the President directly that he should wait for more intel before making the final call. Defense Secretary Robert Gates was also skeptical, warning Obama of the political fallout that came from Jimmy Carter’s failure to secure American hostages from Iran. While Homeland Security Advisor John Brennan and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton were more favorable towards the raid, their support always held some degree of reservation. Outside of CIA Director Leon Panetta, who was reportedly the strongest voice in favor of the raid, everyone was anxious about taking a stance stronger than a soft leaning one way or the other. While Obama was always going to be the one who made the final call, the overwhelming sense of indecision among his staff meant that he had no one to lean on. He was going to have to rely on himself, taking all of the potential political praise, blame, or stagnation that came from this decision. Would he play it safe and contribute further to voters’ ongoing disappointment in him, or would he risk his entire presidency on something with just 60-40 odds?

On April 28th, the President quietly decided to give the go-ahead to a helicopter raid. He would tell his national security team the next morning, and over the next two days, the upcoming mission was constantly on his mind. Even as he was surveying tornado damage in rural Alabama, giving a commencement speech at Miami Dade College, and goading one of his biggest political adversaries into running for his job, Obama was anxiously anticipating the start of this make-or-break event. His charisma allowed him to hide this inner turmoil from the public, but he would later describe this period in a 60 Minutes interview as the longest of his life, only comparable to when his daughter Sasha had come down with meningitis at just three months old. Even on the day of the operation itself, he was careful about what he chose to wear to avoid adding suspicion, eventually settling on staying in his golf attire from a game he had played earlier in the day. When the clock struck 2:00 pm EST on May 1st, Obama and his team headed to the Situation Room to review final preparations. Not long afterward, the President found himself surrounded by his national security team in a windowless room, watching the television like a hawk as he waited to see whether or not his gambit would pay off.

The definitive outcome of the raid wouldn’t be immediately clear for the next few hours; all of the bodies would have to be further identified elsewhere. However, preliminary reporting around 3:50 pm indicated that Obama’s decision to launch a helicopter raid into the Abbottabad compound was a resounding success. Not only had the man himself been taken out and thrown into a body bag along with his associates, but multiple different items from the compound were successfully retrieved for intelligence purposes despite the pitch black darkness and the tight time frame of the mission. Once the identity of Bin Laden had been officially confirmed at 7:01 pm, Obama and his team began to call top congressional leaders to inform them of the news. At 11:35 pm, Obama would officially confirm to the nation that the man behind the worst terrorist attack on American soil was no more.

Celebrations over the news had been occurring before the speech, mostly thanks to a Twitter leak an hour prior. But after the news was certified by the White House, thousands more would go out into the streets to party over the demise of America’s top pariah. In Washington, D.C., chants of “USA! USA! USA!” could be heard from several blocks away. In New York City, the city most afflicted by the 9/11 attacks, celebrations were strongest around Ground Zero, with some climbing the poles around the area with American flags. Even sports games were hit by the news, with the baseball game between the Mets and Phillies that night being interrupted by celebrations among fans, and John Cena announcing the news at a WWE event in Tampa. Even if the death itself had little impact in the grand scheme of things, it still allowed Americans to reclaim a sense of patriotic pride in the fight against terrorism overseas and get some closure on the nearly decade-long effort to catch Bin Laden.

Leadership and Risk-Taking

Despite the gravity of the news, this did not meaningfully change much about the President’s political standing. According to a Gallup poll released soon after Bin Laden’s death, Obama’s approval rating had hit a net positive of +11, his highest numbers since late 2009. However, this bump would disintegrate within just two months, with a Gallup poll from late June seeing his numbers slip back down to -6, similar to what it had been before May 1st.

While this may seem confusing at first, further context of the shifting political tides since 9/11 makes it clearer why this bump was merely temporary. By the time Bin Laden had been killed, fears of terrorism and foreign policy had long since stopped being a top priority among voters. Their concerns instead shifted towards the economy, which had entered a state of pandemonium in late 2008. More so than any other issue, it was the poor economy that put Obama in the Oval Office, and the ever-growing consensus among the public was that he was not doing enough to combat its long-term effects. The economic stimulus did allow the U.S. economy to dig itself out of the crisis, but the package was not large enough to make the ensuing recovery a speedy one. By the time Bin Laden was killed, the unemployment rate still sat at 9.0%, hardly any lower than the 10.0% peak from earlier in his term. Mere months after the killings, the President’s approval rating on the economy hit a new low of just 26%, and almost all the gains he received from the public for killing Bin Laden were long gone. While voters may have appreciated his actions on foreign policy affairs, it was not going to be enough to save his presidency from the ongoing economic sluggishness that voters cared far more about. In the short term, it is hard to deny that the Bin Laden raid had little effect on the President’s increasingly poor image.

However, the long-term analysis shows where the Bin Laden raid fits into the puzzle. Similar to his actions in Iraq, Obama’s decisiveness in fulfilling a campaign promise with efficiency helped contribute to his status as both a change agent and competent executive, both major assets for the campaign trail. However, the Bin Laden experience in particular also left him and his team with two important lessons ahead of his re-election campaign. The first was that voters were more interested in the economy. They would be willing to give him high marks on his achievements elsewhere, but it would not be capable of fully moving the needle because it just wasn't what they were directly concerned about. Success at governing on the foreign policy front was helpful, but it needed to be paired with success on the economic front as well. That leads into the second and more important lesson that goes to the heart of Obama's decision to launch a helicopter raid on the Abbottabad compound: the need to take important risks.

Up to this point, despite being elected on a mandate for sweeping change, the President had largely been risk-averse. The small size of his economic stimulus package had partially been the consequence of Obama seeking Republican support for the bill, leading to the package effectively being engineered by Olympia Snowe and Susan Collins, the two Republican Senators from the Pine Tree State. Most of his cabinet appointments had backing from a considerable chunk of the Senate Republican caucus, with Timothy Geithner’s nomination to the Secretary of the Treasury in particular ultimately being saved by crossover support. Even Obama’s signature achievement—the Affordable Care Act—had been stuck in limbo for well over a year due to his insistence on reaching out to the GOP. While some important legislation was achieved during Obama’s first two years, his record still left a lot to be desired among his increasingly disillusioned base, who had been begging the President to stop reaching out to an opposition party that had explicitly made defeating the President their sole priority. Worse, due to this agonizingly slow progress and the lackluster economy that came with it, there was no bipartisan appreciation towards Obama that replaced the base’s disappointment. It was the worst of both worlds for the President: His bipartisan outreach weakened his ability to fix the nation’s many woes, and he wasn’t even being given credit from the other side for extending his hand out to them.

This flaw did not suddenly disappear once the helicopters landed in Abbottabad. As I’ll delve into in the next parts of this story, Obama would still go on to have moments where he felt it was necessary to reach out to the other side, much to his detriment. But by taking a risk that paid off among the public, even if temporarily, it showed him that there was a benefit to taking chances and expressing strength in his decisions. This kind of posture may not have been in character for him, but it showed the President an opportunity to reclaim the bully pulpit he had long since lost. As had been evident throughout his presidency before May 2nd, resorting back to the vague gestures about hope and change across partisan lines from his 2008 campaign wasn’t going to cut it. With an economy in a continued state of disrepair, people wanted to see positive results from their Commander-in-Chief. Whether or not progress was bipartisan was irrelevant, especially since the Republicans were always going to portray him as a vicious partisan regardless. Simply put, they wanted a leader who got things done, and they saw those qualities in Obama’s handling of the Bin Laden raid.

From there, the goal became how to connect the leadership qualities people liked from Obama here to the issue of the economy. This required reclaiming the bully pulpit, not as a unifier, but as a guy who tried to get things done despite considerable risks and steep opposition. His legislative achievements couldn’t be seen as bipartisan compromises that helped preserve the spirit of cooperation, but instead as the President’s fight for the people being partially thwarted by an elite opposition that insisted on giving more money to the rich and powerful. If it wasn’t for the Republicans and their donors blocking him at every turn, he could have crafted a healthcare bill that didn’t include an unpopular individual mandate. If Republicans couldn’t get Bin Laden after eight years of trying, what makes you think that their leadership could address our growing deficit? By framing his presidency in these terms, it helps present the public with a brand new, far more favorable way to perceive Obama. He wasn’t an unaccomplished neophyte who couldn’t deliver on the promises he expressed in his flowery speeches, but instead an unrelenting ally to the working class held back by an opposition party that cares more about protecting their donors and their party than something that does good for the country.

This kind of rebranding was undeniably risky. Regardless of how unpopular the congressional opposition may be, people aren’t usually quick to blame them instead of the sitting President for the nation’s woes. Jimmy Carter’s infamously poor relationship with the legislative body meant nothing to the public in 1980. George H.W. Bush’s attempts in 1992 to frame the Democratic Congress of the time as the face of the derided establishment completely fell flat. Bill Clinton campaigned against the congressional GOP in 1996, but it was also in the context of a booming economy and relative world peace that he earned widespread credit for. This wasn’t a strategy that had a great track record, and it very well could have backfired if Obama couldn’t deliver this message succinctly.

But if the Bin Laden raid had taught the 44th President anything, there was also great benefit that could come from taking a gamble. And as his polling numbers slipped further throughout 2011, taking this gamble began to look like his last hope for re-election.

Stay Tuned for Part Two!