The Story of Governor Rudy Perpich: America's Goofiest Builder

How the child of Croatian immigrants became the Mesabi Messiah

If there is any tourist attraction from Minnesota you may know about, it’s probably the Mall of America, a massive shopping mall located in the suburban town of Bloomington. Ever since I first went to the mall as a young kid, it’s always been a place I’ve enjoyed visiting. Not only does it contain practically every store and restaurant you could ever want, but it even has a Nickelodeon-themed amusement park and a massive Sea Life Aquarium to add a cherry on top of the experience. Whether you are a kid or an adult, it’s essentially a guarantee you’ll find something you’ll enjoy, making it an extremely attractive tourist destination. There’s a reason why the Mall of America is connected to several different hotels: For many people, the Mall of America is the reason they are visiting the state in the first place.

But you’re probably also asking yourself, why exactly did the Mall of America end up in Minnesota? Why would they put America’s biggest shopping mall in a state that gets forgotten by most people outside of the Midwest? Why would they build a shopping mall in a state that not many were ever considering moving to? Why sacrifice the opportunity to build a mall in the quickly growing Sun Belt?

Well, it came down to many different factors, but one of them was certainly thanks to the marketing skills of one man. In this case, it was a man who spent his entire life trying to build things, with the ultimate goal always being the same: making his state a home for economic prosperity for all. That man was Rudy Perpich, Minnesota’s 34th and 36th Governor.

If you know anything about Rudy Perpich, it’s probably his instrumental role in getting the Mall of America to get built in the first place. His charisma was an incredibly valuable asset throughout the entire process, giving the project a voice that no other person from the state had the opportunity to use. While he wouldn’t be in office to oversee his project’s final completion in 1992, there was no doubt in the eyes of most, even his political adversaries, that his role was indispensable.

But beyond just the symbolism of being the Governor responsible for the creation of America’s greatest shopping mall, there’s another underlying element to his role in this project. People who had lived through his long governorship knew that this wasn’t just some one-off job he did to satisfy Twin Cities business interests. Instead, this was yet another example of something he did throughout his entire tenure as Governor: He was a salesman for Minnesota and its people. This was a mission that he would never deviate from, even in the face of strong political opposition from his own party. He would work with anyone to sell his state, whether it be allies in his own party, businesses long opposed to his political rise, or even other world leaders. While he would experience perhaps the goofiest Greek-esque political downfall, his tenure as Governor would ultimately make him one of the most important people in Minnesota's political history.

In this article, I want to go over the long career of Rudy Perpich, from his start as a Hibbing school board member all the way up to his role as the chief executive of the North Star State. In doing so, I want to show not just his political triumphs and defeats, but also the many decisions he made, both on policy and rhetoric, that still affect Minnesotans today. At the very least, I hope my piece presents you all with a compelling story about one of Minnesota’s most domineering figures. With that all being said, let’s start at the very beginning of his life.

Rudy’s Political Upbringing

Before we get into the start of Rudy Perpich’s political career, we first need to go over the environment and family that he grew up in, as doing so will help us understand not just how he established his ideology and philosophy, but also how he operated the game of politics years down the line.

His father Anton Perpich, born in Croatia (then a part of Austria-Hungary) in 1899, spent his formative years living in the rural countryside assisting his parents on the family farm. The family was poor, under political subjugation, and was the victim of anti-Croatian racism by their Balkan neighbors. While he would try make the most of it, it was never an ideal situation, especially as the First World War was heating up. Eventually, he came to realize that he needed to make a dramatic change if he was to bring himself and his family a stable financial situation. The solution to this turned out to be the one many other Europeans took too: seek a better life in the United States of America.

Settling in the U.S. in the early 1920s, he would find himself in Carson Lake (a part of Hibbing today), a Northern Minnesota town that was seeing an economic boom thanks to the prospering iron ore mining industry. The influence of the industry was everywhere to see in the region, attracting thousands of European immigrants and eventually earning the nickname “Iron Range” for just how influential it was. The backgrounds of the people who immigrated to the region were highly varied, ranging from Finns and Swedes from Northern Europe to Italians and Croatians from Southern Europe. It was an economic gold mine, and people from all over the world were ready to take advantage of it.

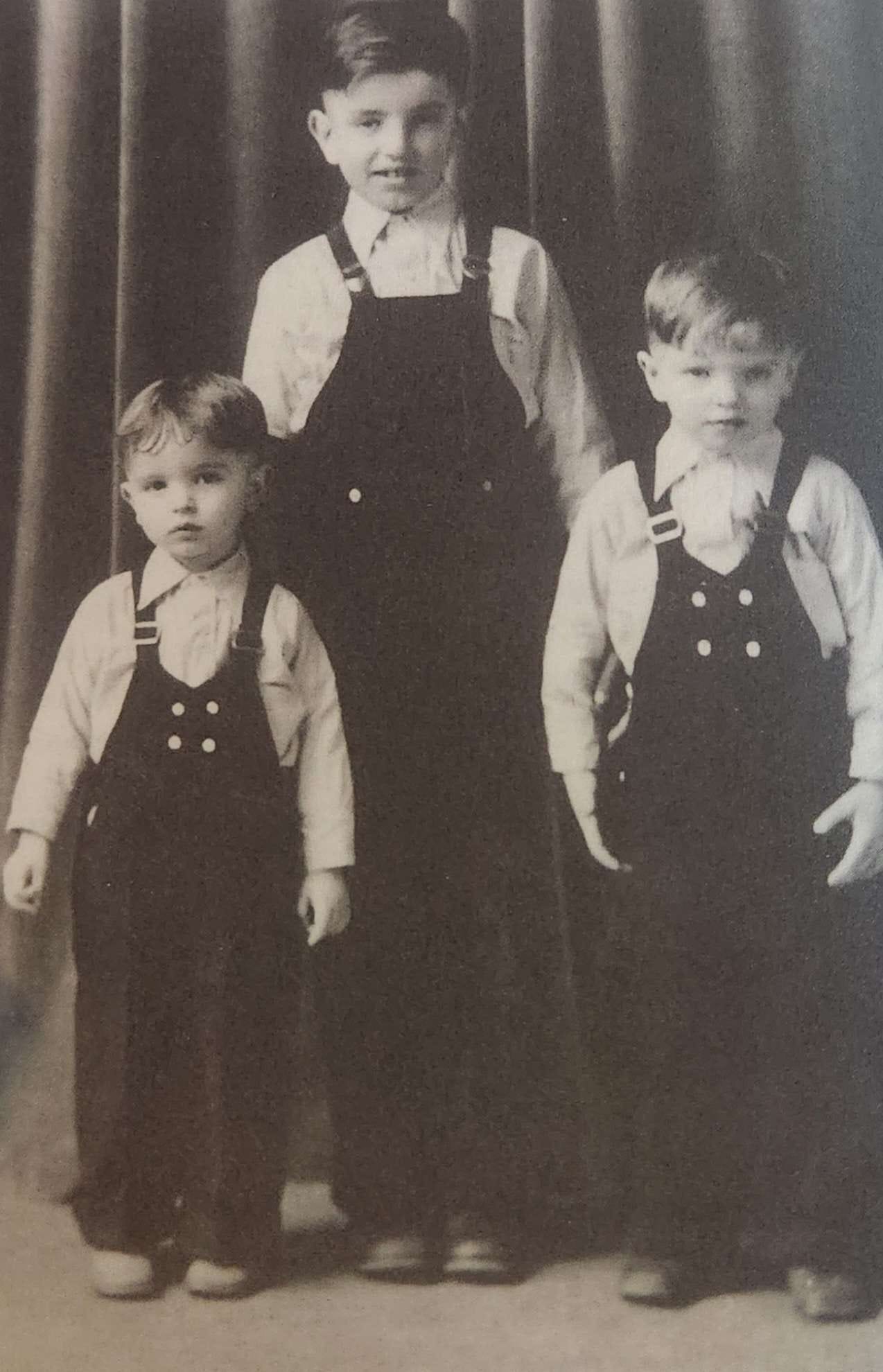

This is the world that Rudy Perpich would be born into in 1928, being the first child of Anton and his American-Croatian wife Mary Vukelich. While Anton and Mary would do quite well for themselves throughout the Roaring 20s, their financial situation would grow much more sour as the Great Depression set in. The Iron Range was hit hard by the Depression, with over 70% of mining jobs being vanished seemingly overnight. This left the family in dire economic straits, with Anton seemingly always on a job search. Their house was small, Rudy and his siblings would all share a bedroom in their three-room house. Anton was almost always at work, usually not being able to be there for his children. They usually couldn’t get any Christmas presents for their children, with Anton even having to tell Rudy one year that Santa wasn’t going to make it, although he would later be saved when a friend of Anton would allow him to buy a gift at a discounted price.

As he grew older, Rudy’s political identity would slowly begin to blossom. While iron mining was a defining feature of the Iron Range, most miners had negative opinions of the companies themselves. The mining companies controlled practically everything in the region, even maintaining control of schools meant for those who weren’t the children of poor miners. Conditions were mediocre, the pay wasn’t adequate, and it seemed like the companies were hoarding all of the money for themselves.

Immigrants, who had long held progressive-leaning politics thanks to their upbringings, would find themselves in conflict with the mining companies they were working for. This resulted in the Iron Range becoming a hub for unionization and progressive politics. Over the course of the early 20th century, this trend began to become more and more apparent, with Progressive Era politicians like Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson drawing a considerable amount of their statewide support from the region.

This would all culminate during the Great Depression in 1936 when incumbent President Franklin Roosevelt was running for re-election. Over the course of his first term, he had established himself as a president for the common man, with that political brand only growing more and more solidified as he signed more of his New Deal agenda into law. While this would anger many in the business community who backed him in 1932, it earned him considerable goodwill with labor unions and workers throughout the Iron Range. While many were skeptical of him in 1932, he became a heroic figure to them over the course of his presidency, and he became incredibly popular among Iron Range voters.

Following the political trend of the Iron Range, Anton and Mary Perpich were staunch Democrats. The two of them idolized Roosevelt, with each of them casting their first-ever vote in an election for him in 1936. This was the election that saw the Iron Range transform into a Democratic stronghold, becoming Roosevelt’s best region in the state by a wide margin, just four years after he barely won it in 1932. The two of them would raise their children with these values in mind, emphasizing the importance of education, helping those in need of assistance, and standing up for yourself in the face of injustice. This would influence not just the many battles that unions would get into with mining companies, but also in dealing with people of different backgrounds too. Anton, who remembered his experiences with discrimination in the Balkans, made it clear that there would be no discrimination of any kind allowed under his roof. Not only would he defend Croatian speakers like himself from discrimination, but he would even show support for an African-American basketball team near his area, which represented a minuscule demographic group that practically no one in the Iron Range had ever interacted with. In his mind, the negative action and attention needed to be placed on the mining companies, and that division based on social class would only result in the mining companies gaining more power.

For Rudy, this is where his political instincts would be born. Thanks to his upbringing, he knew what it was like to be poor, and all the trouble that came with it. He felt that he was uniquely positioned to understand the needs of those who were, in his view, unseen by the government and big business. Just like his parents, he valued education above all other issues, with him later describing it as the “passport out of poverty”. He understood that prejudice against those on the basis of religion, race, or ethnicity was counterproductive and not the ticket to making anyone’s life better. He valued hard work, but also valued helping those who can’t help themselves.

He was a Democrat. But more than that, he was a populist, one who wasn’t afraid to take on the system whom he had always felt at war with throughout his entire childhood. More than anything, that would define everything he did for decades to come at the local, state, and even national level.

From Hibbing to Congress

After briefly serving in the U.S. Army from 1946 to 1948, Rudy Perpich took his parent’s advice about education to heart, enrolling in Hibbing Junior College. While he would prove to be a successful basketball player and was even elected as the president of his sophomore class, he felt that he needed to be in a profession where he could be independent of a boss. After settling on dentistry, he would officially earn his degree in 1954, meaning he wouldn’t have to work in the mines like his father did.

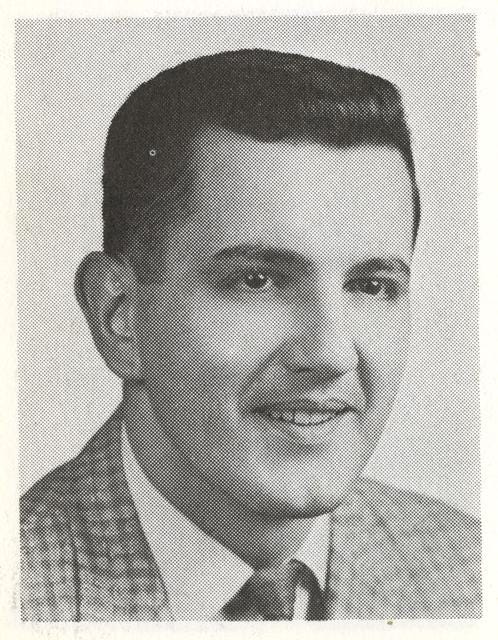

He would set up an independent dentistry practice in Hibbing almost immediately, which would become a near-instant hit with residents, especially with immigrants. Thanks to his likable personality, he quickly became a well-known name in Hibbing, and in 1955, Rudy Perpich put that name to use in his first-ever run for office, the Hibbing School Board. While he was well-known, his Croatian and Catholic background was unheard of for an elected official in the city, leaving many voters uneasy. This resulted in him losing the race, but he was by no means finished here, as he would once again run for the position in 1956. This time, he would capitalize on a hot-button issue, the debate over whether or not female teachers should be paid the same as male teachers, and whether or not married women could be eligible to be hired as full-time teachers. Rudy Perpich, who had been raised to oppose discrimination, would argue on the side of the women, stating that if elected, he would help enact a policy that judged pay on the basis of experience and performance. This was the issue that ultimately pushed him over the top, earning him his first elected office.

As a school board member, Rudy Perpich would successfully make a place for himself as a young, fresh face ready to change the game. Not only did he fulfill his promise to the women who had voted for him over the equal pay issue, but he also forced the board to change its policy regarding gift-giving, something no previous school board member ever bothered to deal with. This made him extremely popular with Hibbing residents, and the acclaim he received in his position soon began to spread the word outside of Hibbing. As time went on, more and more people began to learn who he was, and there were hardly any skeptics to be found. People liked his energy, his passion, and his bold ideas. Obviously, he was going to be something greater.

The way Rudy Perpich went about this surprised everyone, however, when he decided in 1962 that he was going to primary his own DFL State Senator Elmer Peterson, an entrenched incumbent first elected to the State Senate in 1946.

No one, including his own friends, understood what Perpich was doing here. Peterson had the backing of the entire political establishment, including the Iron Range U.S. Congressman and local kingmaker John Blatnik. Incumbents with that kind of backing are not to be messed with, and anyone who does will see their political careers blacklisted and killed off well before it could ever even begin. Party loyalty was an important value, after all, you don’t want to be divided heading into any election. So why would Perpich go against such an important value?

Perpich, who had seen himself as a perpetual outsider since childhood, didn’t have the same interest in preserving party loyalty as many of his peers. While he was a staunch Democrat, he was also someone who considered it secondary to his political goals. In his mind, if there was a Democrat who didn’t subscribe to his values and help the community, they shouldn’t be immune to being challenged by their fellow party members.

This thought was foreign to many in the Iron Range. The region had established a tendency to stick with certain political dynasts, with Elmer Peterson being among them. For that reason, most people didn’t think Perpich had a prayer. Peterson had the legislative experience, the backing of the entire party apparatus, and was a respected statesman by both sides of the aisle. Perpich may have had the energy, but he was just a low-level 34-year-old school board member who frequently went against the party. It was a massive hill to climb, and most people didn’t think Perpich could pull it off.

Despite being dismissed by practically everyone in his personal and political life, Perpich would remain determined to defeat Peterson. Using his charisma to rally his many friends behind him in spite of their doubts, he would spread the word about his candidacy all across the district, using both himself and his enthusiastic supporters to boost him.

This proved to be very successful. As the campaign went on and Perpich continued to make his pitch, the mood began to shift rapidly. While most people in the district liked Peterson, they also felt that he had overstayed his welcome, having been in office for almost two decades by that point. His lead only began to get smaller and smaller, until the final nail in the coffin came when the Republican Party of Minnesota officially endorsed Peterson, seeing him as the lesser evil to Perpich. The Iron Range, where Democratic primaries had been the real election since the days of FDR, took this endorsement as a sign that Peterson was out of touch, voting him out by a margin of just 221 votes.

This narrow loss wouldn’t just end the political career of one of the DFL’s most respected elder statesmen. It would also be the beginning of Rudy Perpich’s march to political dominance in Minnesota, using his influence as a State Senator to become a statewide kingmaker in a way that made him many friends and enemies on both sides of the aisle. The Hibbing School Board was one thing, but now he was a State Senator, now able to create a presence in the heart of the State Capitol in St. Paul. He had the charisma, connections, and thanks to the district’s strong Democratic-lean, had essentially become representative-elect.

And he would take advantage of these traits immediately.

The Perpich-Keith Alliance

Around the same time Rudy Perpich was making his State Senate ascension, the DFL was gearing up to fight in one of the most competitive statewide battles in decades. After losing the Governor’s office in 1960 to Republican Elmer Andersen, the party was eager to take back power in St. Paul, especially as Andersen began to look more and more vulnerable. In order to accomplish this goal, the DFL would nominate the most electable candidate they could, the popular Lieutenant Governor Karl Rolvaag, to take on Andersen in the general election. While this approach was probably the safest one they could have taken if they wanted to defeat Andersen, it also carried a significant risk with it too: the Lieutenant Governor’s office was now an open contest.

As I’ve mentioned in previous articles, the role of the Lieutenant Governor was largely ceremonial, doing little more than serving as a political calculation the main candidate made to broaden their overall appeal and or reinforce their best traits. While doing this was slightly different in 1962 thanks to the two offices being elected separately, the basic principle was still the same. Ideally, you wanted the two candidates to complement each other’s strengths, not deviate and expose their individual weaknesses. With that in mind, Rolvaag and the DFL had a choice to make: who would be their guy?

Once again, the DFL would play it safe, choosing State Senator Sandy Keith as their nominee, clearing the field for him in the process. Just like Rolvaag himself, he was a popular liberal from Southern Minnesota who had managed to win over voters who typically voted for Republicans. After this issue was settled, both Rolvaag and Keith would easily win their primaries, officially making them the statewide symbols of the DFL going into the general election.

At the surface level, this was the definition of a safe pick. It did little more than reinforce everything that made Rolvaag popular, right down to the regions the two men grew up in. It didn’t look like a bad pick, but it was obvious that the DFL was playing it as safely as they could. As the campaign started, most people thought they knew what to expect, and that Keith’s presence would make virtually no difference in the race.

As the campaign progressed, however, Keith’s political instincts would prove to be a valuable asset. Deeply involved with the liberal wing of the DFL, he had noticed the surge of enthusiasm and support for Rudy Perpich very early on, sitting by in shock as Perpich would defeat his own party’s long-time incumbent. Keith, a fellow liberal, saw this as a golden opportunity to help drive votes for him in the Iron Range, which was going to be crucial for any Democratic victory. Perpich would soon host him at his Hibbing office, hitting off with him almost instantly and happily agreeing to help Keith drive votes in the region. He would take Keith all across the region, showing him practically every important spot he needed to stop at in order to appeal to voters, from coffee shops, and restaurants, to even old-timer dances.

This worked out great for both men. For Keith, it was a time to show off his public speaking skills, an especially important asset to present in light of concerns over being seen as an out-of-touch elitist due to his wealthy Rochester upbringing. For Perpich, it was a time to perfect his skills with one-on-one conversations, something that Keith had personally struggled with. While Perpich and Keith had very different upbringings and backgrounds, the two of them complimented each other perfectly, paying dividends on Election Day as the Iron Range would bring both Keith and Rolvaag over the top in their incredibly tight races. In helping Keith win the Lieutenant Governorship, Perpich not only secured an ally at the top of DFL leadership, but he also showed skeptics that he could be a valuable asset himself, one who you would want to have on your good side.

However, while Perpich had proven himself to be an effective ally, some in the establishment still weren’t thrilled with his victory. Not only did he defeat a well-respected incumbent, but thanks to his reputation as an outsider who frequently went against the party, he was also seen as a potential threat to other entrenched incumbents. If he could take down someone as prestigious as Peterson, who knew what would happen if his rapidly growing base went beyond the Iron Range?

The Perpich Problem

After the 1962 election concluded, it was clear that the DFL was split on how to deal with Rudy Perpich’s rapidly growing influence. Those on the more conservative and moderate side were strongly opposed to him, seeing him as an inexperienced loon who could bring the party down in flames. This was the position taken by most of the DFL establishment, including John Blatnik, an adversary of Perpich who expressed concern about his rising influence on his home turf.

On the other hand, more liberal members like Sandy Keith saw his influence as a golden opportunity to keep the party alive in the modern era, viewing him as someone who had the ability to appeal to younger voters who didn’t have as much care for who the incumbent was. For newer DFL politicians, this was the favored viewpoint.

This problem would only grow bigger and bigger as Perpich became a more important figure throughout the 1960s. While the party would stay united in 1964 in the face of Barry Goldwater, the problem would explode into a full-on inner political battle in 1966, when it was announced that Sandy Keith would be primarying Karl Rolvaag for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination over electability concerns. Rudy Perpich, a long-time friend of Keith by this point, would once again assist Keith on the Iron Range, while also assisting his brother Tony in his own primary campaign against entrenched Gilbert incumbent Thomas Vukelich. This was the breaking point for many establishment skeptics, leading to them recruiting Elmer Peterson to take him down in a revenge campaign. After being dismissed in 1962, Rudy Perpich suddenly became the top target of the establishment, and no one was sure if he could take them on.

However, as the 1966 elections progressed, Rudy Perpich emerged out of it much stronger than before. While he wasn’t able to get Keith the statewide primary victory, he would be re-elected to his own seat by a significantly larger margin than he did in 1962, as well as see Tony Perpich defeat Thomas Vukelich, both major blows to the establishment. Not only that, but for the first time, Rudy Perpich and John Blatnik found themselves on the same side of a primary contest, both endorsing Keith in his unsuccessful primary bid. This would be the start of a cooling process between the two kingmakers, neutralizing Rudy Perpich’s biggest political threat in the process. This would have already been significant enough, and a sign that the pro-Perpich wing wasn’t going anywhere.

But it became even more clear in November, when Rolvaag lost his bid for re-election to Republican Harold LeVander, leaving the establishment embarrassed and discredited. While some had attempted to argue that Keith’s disloyalty caused the defeat, this wasn’t what resonated with those in the party. In their minds, Rudy Perpich and his fellow liberals had proven that they were the future of the party. They had the charisma, organizing, and policies needed to bring not just the party into the future, but the state as a whole too.

Of course, he still had enemies, but pretty much all of them were old dinosaurs who just got blamed for the 1966 loss. Rudy Perpich may have been risky, but he was also young, in tune with key DFL constituents, and had the charisma necessary to drive people to the polls. What’s not to love?

Rudy Goes Statewide

Heading into his second term, the 38-year-old Rudy Perpich had established considerable goodwill he never had before. For the first time, he had power within the party, a real presence that allowed his voice to mean something both within the party and Minnesota politics as a whole.

Over the course of his second term, he would never let this opportunity go to waste. As the 1968 elections were approaching, fury over the Vietnam War among the young Democratic base continued to grow stronger each day, with it all culminating in Minnesota’s own U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy announcing that he would be primarying incumbent Democratic president Lyndon Johnson. Rudy Perpich, an opponent of the war, would quickly endorse McCarthy’s campaign, which he would continue to stand by even after Minnesotan Vice President and DFL founder Hubert Humphrey entered the race. Rudy Perpich was deeply involved in the anti-war movement, so much so that many anti-war supporters wanted to recruit him to run in the U.S. House primary against John Blatnik. While Rudy Perpich would decline to take that opportunity, his influence would still bring in a new base of DFL voters, most of whom were younger, and more likely to support Rudy Perpich’s liberal team.

Beyond this, he’d also use his influence to take on the Republicans and big business directly. As property taxes began to slowly increase on Minnesotans over the course of several decades, it became more and more evident that several big corporations were paying virtually nothing, especially compared to what average citizens were paying. Nowhere was this problem more prevalent than in the Iron Range, which saw sharp increases in property taxes for miners while the companies paid nothing in property taxes.

To Rudy Perpich, this was a gross injustice, but it was also one that was easy to fix. When Minnesota’s property tax was implemented in 1941, the state government put a special five-cents-a-ton production tax on mining companies as an alternative for them, which at the time, served its role of generating a significant chunk of revenue while not displeasing the companies too much. But as years went on, most economists had agreed that by 1969, they had been paying far less than they would have under a normal property tax system.

With that in mind, the solution was simple: scrap the production tax and make mining companies pay the same property taxes as everyone else. Of course, this was opposed vigorously by the mining companies, who would make significant efforts to lobby politicians to oppose Perpich and his fellow liberals. Undeterred, Perpich called on those in the Iron Range to not pay their real estate taxes and create a massive tax strike throughout the entire region. When the day came, Perpich fulfilled his promise, organizing on the Capitol and demanding that the Republican Governor do something about this issue.

This effort would prove to be successful. After days of protest, the Republican Governor announced that while he didn’t endorse scrapping the production tax, he did support raising the threshold so the mining companies would have to pay normal rates for the foreseeable future. This was an acceptable compromise for Perpich, and in mid-1969, the legislature passed a bill that raised the tax to eleven and a half cents per ton, more than doubling the previous rate.

This positive attention became a big political win for Perpich, and for the very first time, sparked a real conversation about his potential on a statewide level. He was a rising star and had demonstrated he could get a big political win for his people, even in the face of Republican opposition. Who knew what he could do if given a statewide spotlight?

Rudy Perpich, a deeply ambitious man, would soon announce his intention to seek the DFL nomination for Lieutenant Governor, taking out a $20,000 loan for his campaign in the process. For the first few months, the process was tiring for both Rudy and his wife Lola, who kept having to commute from their Hibbing home all the way down to the Twin Cities every single day, taking several hours both ways. But this tedious time would soon come to an end as Rudy Perpich approached the next problem: the state convention.

While Rudy Perpich was a far less toxic politician in establishment circles than he was eight years prior, he still had significant work to do if he was going to receive the party endorsement. While he was successful in getting John Blatnik to stay neutral in the primary, he still needed to get key allies to support him.

Fortunately for him, he would have a considerable amount of time to build up that support. While Perpich was building up a base of supporters, the establishment struggled to find a reliable alternative. Wendell Anderson, the frontrunner for the gubernatorial nomination, alongside U.S. Senators Walter Mondale and Hubert Humphrey all requested David Graven, a University of Minnesota professor to be his running mate, spending a considerable amount of time to convince him. Ultimately, however, Graven would choose to decline this opportunity, and since Perpich had already secured several important DFL endorsements by that point, a fight against him was going to be extremely tough.

In theory, this is where the establishment could have chosen to take their stand, and if they did, it’s very possible they could have succeeded in stopping Perpich. But Wendell Anderson, who had just won the DFL endorsement for Governor, knew that this upcoming election was not going to be an easy one. Perhaps they could take down Perpich, but doing so would require a significant amount of blood, sweat, and tears that could jeopardize party unity ahead of the 1970 election. So, in order to avoid that, Anderson agreed to sign on with Perpich, making the two of them the DFL-endorsed candidates heading into November.

This campaign, which would be the last one where the Lieutenant Governor and Governor were elected separately, would prove to be an incredibly tough fight for Perpich. He had considerable goodwill with Iron Range voters and many in the DFL, but his name recognition was still quite low, allowing many of his biggest adversaries to define him. All across the state, many of Perpich’s biggest enemies would make advertisements and billboards in opposition to him, with some even telling people to vote for Wendell Anderson and Ben Boo, Perpich’s opponent. Many in the establishment wanted nothing to do with Perpich, even banning him from appearing on shows where Anderson and Humphrey would be appearing. Over the course of the election, it seemed like the outcome was already set: Anderson would win, and Perpich would lose, creating a split verdict for the first time since 1960.

But unfortunately for Perpich’s enemies, their attempt to frame the debate would backfire on them. While Perpich would significantly underperform the rest of the DFL ticket, he came out victorious when all was said and done, making him a top DFL official and the first-ever statewide official from the Iron Range. Not only that, but both of Rudy’s brothers would be coming to the Capitol with him too, with Tony being re-elected and George winning Rudy’s old seat.

Once again, Rudy Perpich had taken on the system, and just like every time before, he would come out of it victorious. Outside of his low-profile 1955 Hibbing School Board run, he had never been able to lose a race despite frequently being the target of establishment vigor. The establishment didn’t want to admit it, but it was clear: They couldn’t take him down. He was just too good of a politician, simple as that. They were just going to have to accept that. He’s part of the party now. He’s their lieutenant governor, after all.

Minnesota Minutes

Taking office as Minnesota’s 39th Lieutenant Governor on January 4th, 1971, Rudy Perpich had finally taken control of one of Minnesota’s sought-after statewide offices. Sure, it wasn’t a particularly special one: The Lieutenant Governor didn’t play a huge role in governing. But with someone as energetic as Rudy Perpich taking the wheel, the role that this otherwise unremarkable position would serve would be like nothing anyone had ever seen before.

Immediately upon taking office, Perpich would get to work using his newfound status to full benefit. Despite the wishes of many in Wendell Anderson’s inner circle, Perpich had effectively become the person responsible for presenting the administration’s message on several important issues, whether it be rising healthcare costs, dirty mines in the Iron Range, or opposition to conservative-written omnibus bills. While his role was typically positive, his less-than-elegant speaking ability sometimes worried those in Anderson’s inner circle, leading to a chilly relationship between Perpich and Anderson’s staffers throughout his entire tenure.

This increased presence allowed him to play a bigger role in inner-party politics as well. While ideology suggested that Perpich would have been more inclined to back South Dakota U.S. Senator George McGovern’s 1972 presidential campaign, he would instead stay loyal to his party’s creator Hubert Humphrey, despite his personal top choice being Massachusetts U.S. Senator Ted Kennedy. While this did help out Humphrey considerably, the young forces who backed McGovern ultimately won out, forcing the DFL to put much of their priorities in its official platform, such as legalizing gay marriage and pardoning Vietnam War draft dodgers. Most of the DFL office holders would disavow this platform, a move that would serve them well as the McGovern ticket went down in a landslide defeat against incumbent president Richard Nixon. In retrospect, Perpich’s decision to stick with Humphrey instead of going by ideology would serve him incredibly well, as it meant that he wasn’t associated with McGovern’s massive defeat, keeping his own brand alive in the process.

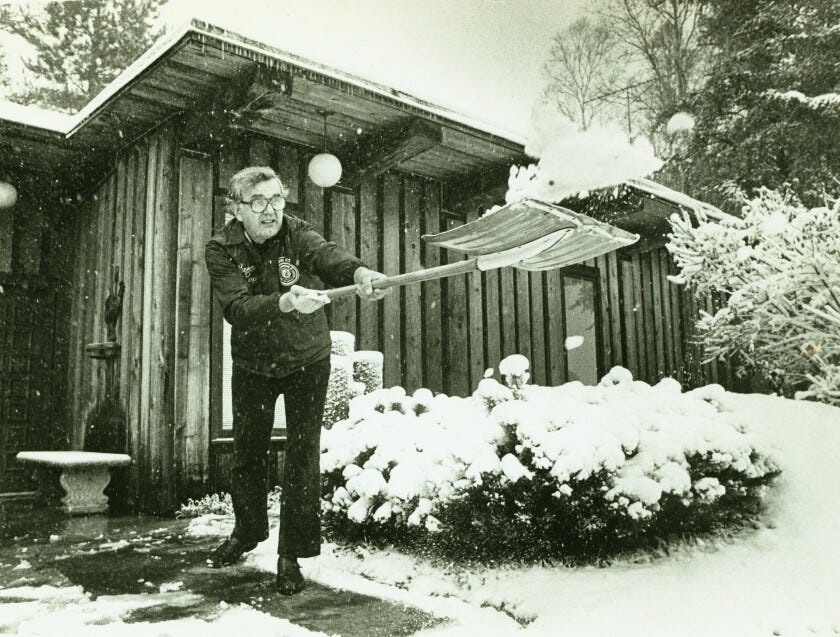

Over the next few years, Perpich would begin to see his influence grow larger every day, with him effectively becoming a legislative liaison to Anderson. The governor, annoyed at Perpich’s high energy, would seek to pacify him by giving him several different assignments to lead, from planting trees, re-building dying infrastructure, and fixing billboards. While Perpich could tell why Anderson was doing this, he would happily accept it anyway, seeing it as an opportunity to continue building his statewide profile while pursuing something he felt was essential: revitalizing what he described as Greater Minnesota, the part of Minnesota outside the Twin Cities metro. This would be the first time he’d head up such a project, and it certainly won’t be the last we’ll see in this piece.

He would travel everywhere throughout the state, visiting places that no politician had visited in decades. He absolutely loved it, meeting new people whenever he could. While on the road, he would also become a name on local radio, asking local stations to play his “Minnesota Minutes” tapes, in which he would discuss his travels, the administration’s priorities, and his view on Capitol drama. He would send in these tapes constantly over the course of two years, instantly making him a household name in the process. Once unknown to those outside his Iron Range world, no one could forget who he was now. He was literally everywhere, you couldn’t miss him even if you wanted to. For the first time, practically everyone knew who Rudy Perpich was.

Rudy Perpich, aware of his newfound influence, would use much of it in 1974, when John Blatnik announced that he was going to retire, leaving an open primary contest for the first time since 1946. Blatnik and his allies would back Jim Oberstar, a Blatnik staffer who held more conservative views on issues like abortion and gun rights. Perpich would back his brother Tony, who held a liberal view on both issues. It was a showdown between two political dynasties, and it was anyone’s game.

Ultimately though, while Tony would secure the party endorsement, he ended up getting trounced by Oberstar. This was the first election cycle that occurred after the Supreme Court ruling of Roe v. Wade, which saw abortion rights legalized all across the United States. The Iron Range was generally divided on abortion rights, but since it was an issue hardly anyone cared about prior to Roe, candidates’ position on it wasn’t relevant in the eyes of most voters. However, that all changed in 1974 when Tony’s pro-choice stance suddenly became a large liability as millions of dollars from anti-abortion poured in to oppose. While Rudy did what he could to fight back, he was unable to take them down, and Oberstar would reap the benefits. It was a significant defeat for the Perpich machine and a sign that it was more vulnerable than many thought.

However, Rudy Perpich wouldn’t have a lot of time to be upset about the end of his brother’s political career. Heading into 1976, he had a far more important thing to be getting prepared for. It was something he didn’t expect to be handed to him, nor was it something that his parents ever thought he or his brothers would ever be doing. But it was something that Rudy was eager to take on, even while acknowledging many of the consequences that came with it.

The Gray Goose Governor

By 1976, it was obvious to everyone in the state that Rudy Perpich wanted to become the Governor of Minnesota. He certainly didn’t hate his current position, but he was also acutely aware of the limitations it had. While he was a great salesman for the Minnesota Miracle and a strong leader on the issues handed to him, he was also in no position to delegate policy in his own right. While Perpich liked Anderson, he was never fond of having a boss. After all, why else would he pursue an independent dentistry career? He had always been his own man, and he was ready to lead.

Of course, actually doing that was a lot easier said than done. While he had become a household name, he had also been in office for over five years at that point. While the magic was still alive and well for many, some had begun to grow tired of him, especially since his party had been in control of the state since 1970. If he were to run for a term of his own in 1978, he very well could have lost solely on the basis of people being tired of him. Simply put, the path to a Perpich administration was going to be tough, and if he wasn’t able to get it done, he could have gone down in history as just another bureaucrat.

But as the year progressed, 1976 was beginning to look like the year where everything would change. As the DNC conventions started, Jimmy Carter, a former Georgia governor who had just won the Democratic nomination, announced that Walter Mondale would be joining him as the vice presidential candidate on the ticket. This meant that if they had won in November, Anderson would be left to pick a replacement for Mondale’s vacant U.S. Senate seat.

At first, this didn’t mean much to Rudy Perpich. He never held much interest in pursuing federal office beyond just the benefit of giving him a springboard to a statewide role. Since his passions were primarily in statewide affairs, and since his status as lieutenant governor meant that such a springboard was unnecessary, this vacant Senate seat didn’t mean much.

But Wendell Anderson, a deeply ambitious politician in his own right, saw this seat very differently from Perpich. To him, this was what he needed to begin a political star role of his own. More than just a job promotion, he viewed it as his ticket to being the worthy successor to Mondale’s legacy, the new DFL aire who was going to define statewide politics for decades to come. For Anderson, this would be the end of his service in statewide politics, and the beginning of a national rise.

Very soon after Anderson started seriously considering making this step, it began to be known to Rudy Perpich thanks to speculation from the press. He wanted to be Governor just as bad as Anderson wanted to be a U.S. Senator, and he saw Anderson’s plan as a win-win for both of them. To him, the plan was perfect. But there was a big issue: The two men had never talked about this issue before, and for many months, Perpich was oblivious to what he was going to do. While he would meet with the governor after the DNC convention, Anderson didn’t give him any definitive answers on his future, only saying that he was still considering it. This was a position that Anderson would stick to for months, something that irritated the anxiously waiting Perpich. Even after the Carter-Mondale ticket won the presidency, Anderson still didn’t give Perpich any signs. Rudy Perpich had concluded that it was over, telling his family on the morning of November 9th that he did not think that Anderson would go through with it, especially in light of polls showing the majority of Minnesotans disapproved of such a deal.

But just a few hours later, he would receive a call from Anderson’s Chief of Staff, who simply told Perpich that Anderson wanted to meet with him the very next morning. While he wasn’t told what to expect by the Governor, Perpich knew exactly what it was. He was excited, so excited that he could barely sleep that night. Finally, he could shape the state in the image that he wanted. He could be in a role where his salesmanship had the power to back it up. He could become the Mesabi Messiah, the first Governor to ever hail from the vast Iron Range.

The next morning, as Perpich was officially told by Anderson that he was going to be the next Governor, preparation to assume the job went underway immediately. Standing alongside his family on November 10th in a room full of reporters, Perpich declared it the “best day of his life”, and that he was ready to act immediately, effectively serving as the governor designate until Mondale resigned from the U.S. Senate.

For this brief period, he wasn’t able to get much done, as Anderson’s advisors were still keen on limiting his influence so as to prevent the future Governor from putting his foot in his mouth. But unlike before, in the long term, Perpich had the upper hand. Rather than spend his time frustrated by the limitations of his job, he would spend this time preparing a team to work alongside him, which even included his own brother George. He was so active that he would earn the reputation of a gray goose for his workaholic tendencies, which frequently involved him flying from his home in Hibbing back to the state capitol.

Finally, on December 29th, Perpich would officially be sworn into office as the Governor of Minnesota, the first from the Iron Range and the first of Eastern European descent. In his short inaugural speech, Perpich would make education his #1 issue, mentioning his initial inability to speak English as a kid as an example of how the education system helped him and in the process, created a world where someone like him could be Governor of Minnesota. The speech was well received, with its short nature being praised by critics who considered it an example of how the Governor wouldn’t waste time that would come at the expense of working for Minnesota. For Rudy Perpich, it was the best day of his life, and he had every reason to be excited.

Unfortunately, this would be the best day he’d get for a long, long time.

The Downfall of the Bocce King

When Perpich assumed the office, he came in during a time of uncertainty for many Minnesotans. The economy was shakey, voters had largely disapproved of Anderson’s politically motivated promotion, and Minnesota Republicans sensed an opportunity to flip the governorship back into their column, seeing Perpich as a weak opponent who they could easily defeat if they played their cards right. While most in the DFL viewed Perpich favorably, he would have to prove that he had the ability to lead them into the 1978 elections just under two years from when he was sworn in. With that in mind, how did Perpich’s first term go?

Initially, most people seemed to like the new governor. Knowing that most people had grown distrustful of their government in light of national scandals, Perpich would make his office and presence more common than any governor in decades. While every governor before him had held their meetings with cabinet privately, Perpich would open these meetings up with the press, arguing that he had nothing to hide from the public he served. While this annoyed some of his staffers, it fed into his image as a people’s governor, someone who clearly broke from Anderson and other DFL establishment politicians in a meaningful way. The governor would also keep up his active schedule. He was seemingly everywhere, sometimes not even informing his staff where he was at all times. It didn’t matter if you lived in the Twin Cities or Greater Minnesota, it was always easy to meet the new governor and ask him questions. Thanks to this, Perpich would remain consistently popular throughout his first year, and going into 1978, he looked like a solid favorite for re-election.

But over the course of his second year, his political brand looked weaker with each passing day. While the people approved of his transparency, this also led to the exposure of many internal political fights that would have otherwise been hidden. The DFL establishment, who had long been skeptical of Perpich, frequently expressed their frustration with his tenure over several different issues, whether it be with his fights with the Reverse Mining Company over pollution, his appointment of a feminist liberal judge named Rosalie Wahl to the state Supreme Court, and his more conservative views on issues like abortion rights and guns. Many of these internal fights had been made public, giving them the impression of a party that was tearing itself apart.

Adding onto this was the birth of one of Perpich’s most famous political traits: his goofiness. This came after it was revealed that he donated his entire bonus paycheck to support the sport of bocce, an Italian sport that most Minnesotans had never heard of. Republicans used this as proof of Perpich’s unseriousness, and while the nickname would come later, it would be the first instance of “Governor Goofy” that the public got to see.

Adding onto Minnesotans’ desire for change after decades of DFL dominance and the death of Hubert Humphrey, it was a situation that didn’t paint an especially rosy picture for Perpich. But it would made worse by two major problems: the GOP and DFL.

For the former, the Republicans would nominate Congressman Al Quie to run against him, a popular Southern Minnesota congressman who had a knack for campaigning. Perpich, who became far more interested in governing than campaigning during his time as Governor, had begun to look slow and out of it next to the energetic and active Quie, who was putting up billboards and signs all across the state. Without a doubt, the Republicans had more energy on their side, putting the incumbent in serious danger already.

As for the latter, this would be the issue that Perpich would later argue sealed his fate. As the general campaign was heating up for the two U.S. Senate seats, the DFL would come out of the primary process severely weakened. Wendell Anderson, once seen as a future DFL star, had grown increasingly unpopular thanks to his obvious ambition and various poor votes as a U.S. Senator. His opponent, Republican businessman Rudy Boschwitz, would tap into the disappointment many had about Anderson, running as a moderate Republican running in opposition to a self-interested politician. For most Minnesotans, this was more than enough, and Boschwitz began to take big leads over Anderson in the polls.

The other U.S. Senate seat would see a bitter primary fight between liberal Bob Fraser and conservative Bob Short, the latter of which eventually won out thanks to support from the Iron Range. Short, who was to the right of his Republican opponent David Durenberger on several issues, had virtually no appeal with the DFL’s sizable liberal coalition, effectively dooming his campaign altogether. Once again, a big fumble by the DFL.

While Perpich wouldn’t have the same kind of appeal issues that Anderson and Short had, their downfalls would prove to serve as an anchor on Perpich’s ship, consistently holding him back from gaining bipartisan support in the same fashion as he had hoped. The DFL brand, which had been the dominant party in the state for decades by that point, had become toxic seemingly overnight. While Perpich would do the best he could to prevent the toxicity from killing his campaign, it would ultimately prove to be a fruitless effort.

On Election Day 1978, the DFL would see itself completely swept out of power on almost every major level. Both of the U.S. Senate seats, which had been held by the party since 1958, would both be lost by landslide margins. While the DFL-held State Senate wasn’t up for re-election, the DFL would still see considerable losses in the State House, with the chamber eventually tying at 67-67, a crushing blow for the party. Finally, Perpich would lose his own campaign for a full term to Al Quie, his first loss since his first run for the Hibbing School Board 23 years earlier. For Perpich, it felt like the end of the world, even describing it as “falling off the edge of a cliff”. To most, it looked like his only legacy would be as a goofy salesman, a man who didn’t get a lot done despite his own wishes.

But just like his 1955 loss, Perpich wouldn’t take a defeat lying down. He wouldn’t allow his characteristics or the political environment to define him. He was ready to set his future on his own terms. But how did he do that?

The Colorful Comeback

After leaving office, Perpich would immediately get to work on starting a comeback effort. While he would spend most of the four-year period out of the public eye and work in Vienna, he was quite planning out how he was going to win a campaign, both in the primary and general election. After resigning from his job in April of 1982, he would return to Minnesota and announce his long-anticipated comeback bid, ready to execute his plan. But what exactly was his plan?

Firstly, he would make it clear that whoever the party endorsed was irrelevant, and that he would stay in the primary regardless. This instantly made him an outsider to the party establishment once again in the eyes of many Minnesotans, even more so after the party endorsed his main opponent, the State Attorney General and liberal DFLer Warren Spannaus. While this first decision helped distinguish Perpich from the reputation-recovering DFL, it carried the problem of voters not seeing him as the default choice, which had the potential to throw the election in favor of Spannaus. Perpich was not going to be able to rely on his image, he’d have to do the work necessary to win.

This is where his second strategy came in, a catchy slogan. In this case, it was a pretty simple one: “Jobs, Jobs Jobs”. On top of being memorable, buttons and campaign merch with this slogan were also very cheap to produce and pay for, only being sold for a single dollar. This made them easy to find and buy for anyone in the state, playing into Perpich’s image as someone whose top priority is helping all Minnesotans first and foremost.

As the campaign went on, no one could really tell who was going to win. Both sides would do whatever they could to win votes, with Rudy Perpich even taking the historic step of picking a woman, businesswoman Marlene Johnson, to be his running mate, the first in state history. As the campaign went on, it was clear that both of the candidates had clear bases, paths to win, and passionate supporters. As the primary day came, no one knew what to expect, and both candidates would spend their last minutes driving voters to the polls, with Rudy Perpich getting friends to play music in the Iron Range to go out and vote for one of their own.

Early on in the night, the result looked very poor for Perpich. The Twin Cities metro would come in first, where liberal DFLers would deliver Spannaus thousands of votes that looked impossible to overcome. In both Hennepin and Ramsey Counties, the biggest counties in the state, Perpich could barely even crack 30% of the vote. While the Perpich team didn’t expect to do well in the region, they never expected to be quite this bad. Very quickly, the campaign became demoralized, with blame going around on all ends.

But as the night went on, the fighting began to turn into celebration as the Twin Cities vote was complete, and Greater Minnesota votes had finally begun to be reported. These were ballots far more favorable to Perpich and got him very close to overtaking Spannaus. Just like it had done for John F. Kennedy in 1960, the Iron Range would prove to be the place that put Perpich over the top, officially taking the lead for the first time that night. Just a few hours after that, at around 4 in the morning, Perpich had won the primary, making him the official DFL candidate going into the general.

After this bitter campaign, Perpich would use much of the same strategies he employed against Spannaus against his Republican opponent Wheelock Whitney, a candidate who also beat back the endorsed candidate in his own party. Despite Whitney’s charisma, his campaign never proved to have the same steam as Al Quie. For one thing, the once fresh GOP had quickly grown stale to Minnesotans, as Al Quie made several budget mistakes so severe he was forced to drop out of the 1982 election altogether. This left Whitney badly damaged, especially up against a former governor many Minnesotans had fond memories of. On top of this, Whitney’s attacks on Perpich for his goofiness didn’t stick the landing as much either, as most Minnesotans had spent the last four years reminiscing on the days when the bocce goofball was the head of the state. Simply put, Perpich had his work cut out for him, especially as his party’s leader Mike Hatch made sure that the party remained united around him.

When Election Day came, the result was a stunning success for Rudy Perpich. While many other DFL candidates went down in defeat, Perpich would defeat Whitney in a landslide, earning 58.8% of the vote to Whitney’s 39.9%. His performance was a spectacular comeback, particularly in the Iron Range, where he would put up some of the best margins ever seen for a DFL candidate in history. While he was dismissed four years ago as a lame-duck goofball, no one could deny it now. Rudy Perpich was a real force to be reckoned with, having an appeal that not many other statewide politicians could match.

Rudy Goes Worldwide

Just like his inaugural speech in 1976, Perpich would immediately list education as his number #1 priority for essentially the same reasons he listed then. This time, however, he had learned from many of his past mistakes and was no longer seen as someone who could be easily beaten by the GOP or the liberal metro wing of the DFL.

Accompanying this newfound experience were several changes he made in governing. While he would still run a government far more transparent than governors before him, he would use private meetings for special purposes, both in order to keep internal fights from being exposed and to keep his advisors happy. While Minnesotans still liked transparency, it wasn’t on their minds nearly as much as it was in the post-Watergate 1970s period, so Perpich felt that openness to the extent he had it in his first term was unnecessary and self-defeating.

Additionally, Perpich would begin to use his office in a way that fulfilled his desire as a salesman for Minnesota. This involved working directly with businesses, often being right in the center of negotiation with them to create jobs in the state. While many were surprised that he would do this given his record of fighting big business, it made sense from a campaign perspective. After all, Perpich had won in a landslide on the promise of “Jobs, Jobs, Jobs”, and one of the best ways to do that is to encourage companies to create them. While Perpich often felt uneasy about it, he considered it a necessary evil for achieving his goals.

Just as he had always done, however, this salesman role would also get him in fights with both parties and even other states. The most notable example of this came in 1983, when the Governor of South Dakota, Republican Bill Janklow, spent a considerable amount of time portraying Minnesota as a high-tax, anti-business state that couldn’t compare with South Dakota’s business-friendly climate. This deeply angered Perpich, who would later challenge the South Dakota Republican to a debate, which Janklow would accept. The debate, which happened on March 18th of 1983, mostly consisted of the two men trading insults back and forth, a bitter show that showed off Perpich’s willingness to get in the mud if it meant protecting Minnesota jobs.

While his role as a salesman often left Perpich exhausted from fights, it did serve in creating one of the most iconic traits about the Governor today: his missions abroad. Very early on in his governorship, Perpich had made it clear to Minnesotans that the global economy was going to play a key role in his handling of the state, and that he was willing to work whenever he could with them if it meant getting jobs to the state. This promise was kept very early on, when he would travel to Europe and get meetings with virtually every representative for each country, even making Minnesota the first state in the U.S. to open a trade office in Scandinavia.

This newfound experience, and the policy changes that came with it, made Perpich incredibly popular. In spite of Republican attempts to paint the new governor as an anti-business liberal, it would prove fruitless as Perpich consistently exceeded 70%+ approval ratings throughout his first two years in office. Despite being in politics for almost three decades by that point, most people saw him as new and fresh, a symbol of a new DFL free from much of its past troubles.

But while Perpich was very popular, this popularity didn’t put much of a dent in Republican support. Throughout his entire first term, the Republicans had remained a strong force in the state, with both their national and statewide incumbents being well-liked. While Perpich had established a strong brand, it wasn’t one that could carry his party to newfound success down-ballot.

This problem became evident in the 1984 election. While Walter Mondale would be able to hold onto his home state in the face of a bright red Reagan tsunami, his extremely minuscule victory margin of just 0.3% proved to be enough for Republicans to flip the State House, meaning that Perpich would be forced to negotiate with the GOP. In particular, he would have to negotiate with David Jennings, a long-time foe and deeply conservative politician who had promised his party that he would fight for tax breaks and cuts in government spending.

Rudy Loves Chopsticks

Heading into the 1985 session, both Perpich and Jennings knew that they would have a lot to argue about. The two men had been political rivals for decades, both climbing the political ladder in their own ways, until finally leading to the two men being in direct competition with each other over the future of the state. It felt like fate had put them there to fight, and the two were certainly ready to go at it.

But they had also shared commitments with their own voters that happened to put them on the same side of other issues too. In particular, both sides had made a promise to their voters to get tax cuts, a policy that had grown increasingly appetizing to both citizens and politicians. Minnesota had long been criticized by business interests and citizens as a high-tax state, and both candidates were ready to address it for political brownie points. Tax cuts were going to happen, the only question was who was going to get more out of it.

Initially, Jennings wanted to pair it with cuts to welfare and social services, seeing it as essential to funding the tax cuts. Perpich wanted no part of this, considering it a non-starter and pledging to veto it if it ever came to his desk. After this budget went down in defeat to the Governor, Perpich and the GOP would spend considerable time negotiating, before finally settling on a plan that saw wealthy loopholes close, tax rates go down on the middle class, and no cuts to social services. While both sides would celebrate their triumphs, it was obvious that Perpich had gotten the better hand in the exchange, saving thousands of Minnesotans from suffering to burden of social service cuts.

But besides the tax cut victory, Perpich’s next two years would prove to be far more tumultuous than his first two. When it came to education policy, he would go against many of his party’s preferred policies, instead choosing to adopt a school choice policy that earned support from the Republican legislature. While this did fulfill his promise of making significant changes to education policy, it was done in a way that angered many in his own party, as well as organizations that had backed him for his entire career. He would also be criticized for spending too much time trying to get support for a Megamall project (later known as the Mall of America), something he would have to postpone anyway in light of lackluster support from both the DFL and GOP. Finally, the strong economy that had brought him significant popularity in 1983 and 1984 began to slowly decline in the face of a major farm crisis that hit the Midwest in the mid-1980s. Perpich had spent years touting the strong economy as his doing and reaping the political benefits, and now that it was declining, he was reaping the political consequences of it too.

All of this made Perpich’s re-election effort look concerning. Not only was he at risk of losing to a Republican, but he was also at risk of losing the primary to a liberal DFLer. He was going to have to do something quickly in order to save his effort, otherwise, he would go down in defeat and pave the way for a conservative Republican to get into office, potentially reshaping the state in the process. So, how would Perpich turn it around?

Going in 1986, he would play the offensive very early on, running TV ads arguing that his plans and policy achievements fell in line with his goal of “Moving Minnesota Forward”, with him taking full credit for the tax cuts in the process. Republicans protested this, but since they didn’t get much out of it and didn’t hold the Governor’s salesman charisma, their attacks didn’t register. On top of this, he would also make peace with the DFL endorsement process, getting the party chair Ruth Esala to help secure the nomination for him. Both of these strategies had benefitted him massively, once again putting him back on the map as a strong candidate heading into 1986.

But it was by no means over at this point. The liberal wing of the DFL, long frustrated with the Governor’s new moderate bent and lack of focus on the Twin Cities metro, would run St. Paul Mayor George Latimer as a primary challenger. Once an ally of Perpich, he felt that the Governor had been disappointing, arguing that he didn’t go far enough in support of the party and the Twin Cities base.

While this was an appealing message to metro liberals, it didn’t extend much beyond that, especially as Latimer would frequently make attacks against much older Greater Minnesota DFLers, which offended them and caused them to fall in line with Perpich. On top of this, Latimer proved to be a terrible fundraiser, being significantly in debt while Perpich had a strong war chest. While Perpich would prove to be an effective campaigner in his own right, the failures of Latimer’s campaign would prove to be the deciding factor in the election, as Perpich defeated Latimer by just under 17 points, losing only three metro counties in the process.

Having successfully beaten back the liberal wing of his party, it was time to face off against the conservative Republicans. This time, they would nominate Cal Ludeman, who had a different approach to dealing with Perpich. While he would also take shots at Perpich’s goofiness, he would do so in a way that emphasized how it put the state economy in jeopardy. In particular, he spent a considerable amount of time attacking Perpich for his effort to build a chopstick factory in his home city of Hibbing, a project that didn’t create anywhere near as many jobs as the Governor expected. This would be mocked in Ludeman's ads, using Perpich’s goofy traits as an attack against his credibility.

However, most people didn’t care much about this. Most people had known Perpich was a goofy guy, anyone who was going to vote against him for it already did in 1978 and 1982. On top of this, Ludeman’s conservatism proved to be a turnoff to more moderate Republicans, many of whom didn’t even show up on Election Day. Combining this with the DFL being united around Perpich, it created a perfect storm for the Governor on Election Day, who would win re-election with 56.1% of the vote to Ludeman’s 43.1%. On top of this, the lack of GOP votes also allowed the DFL to be swept back into power, flipping the State House and all statewide offices besides the State Auditor’s office.

When all was said and done, it was a smashing success for the DFL and Perpich. Once entering 1986 in danger, they had left it with more political power than ever. There wasn’t even a Humphrey or Mondale that could have been said to bring Perpich over the line. This time, the success was his and his alone. For the first time, the Governor was not the outsider, but rather the center of the DFL, no longer reliant on a Humphrey or Mondale to win in the eyes of voters.

Rudy the Builder

Heading into his third term, Rudy Perpich had more political capital than ever. Sure, the election he had won had low turnout, but the people who actually voted gave him and his party a sweeping mandate. Who cares if not many people voted? They still had it, and it would be stupid not to use it. But what did the Governor decide to do with it?

Immediately after the 1987 session started, the Governor immediately got to work on passing his most notable legacy item today: the Greater Minnesota Corporation. Long frustrated with the lack of care that Greater Minnesota got, Perpich would seek to create an agency that didn’t just create short-term growth for the area but created long-term investment needed to keep the region up with the metro. Thanks to his project, billions of dollars were poured into research, new product development, assistance for farmers, and rural business grants. While much of his desired reforms to the program would go down in defeat years later, it was still Perpich’s proudest achievement by far, considering it the most significant piece of state legislation in decades.

Alongside this, Perpich’s reputation as a builder would be born here too. While he wouldn’t attend its opening due to perceived negative media attention, he would preside over the completion of the Minnesota World Trade Center (today known as the Wells Fargo place), as well as secure funding and support for the Mall of America, both massive parts of his legacy today. Over the course of his third term, almost every budget would include the construction of a new building project backed by the Governor himself, who viewed it as essential to building the image of Minnesota as a place open for business and residence. He was willing to build pretty much anything, whether it be history centers, Olympic Sports Facilities, new parks for communities, or even renovations of old state buildings. While some at the time criticized it as unnecessary, many of his buildings remain alive and prosperous today, leaving behind a legacy far easier to see than many governors before and after him.

All of this positive attention began to earn him speculation as a future presidential candidate for the 1988 election. While initially hesitant to abandon the state he loved and spent his entire career catering to, he slowly began to consider the idea, seeing himself in the same light as Walter Mondale and Hubert Humphrey, both Minnesotans who made a national splash in their own rights. Sure, he was a socially moderate Governor from Minnesota, but Jimmy Carter was also a socially moderate Governor, and that didn’t stop him.

But as this idea was being seriously discussed, many of his enemies in the local media began to lampoon the idea. Most Minnesotans wanted him to stick out his four-year term, liberal DFLers dismissed him over his anti-abortion and pro-gun views, and Perpich didn’t have the national organizing that would be necessary to run a campaign. While he thought he could make a good candidate, he decided to bow out of the contest, announcing in September of 1987 that he was not going to run, officially killing off any hope of a national Perpich profile.

While not many at the time noticed it, this was the first ominous sign for the future of Rudy Perpich’s political career. While his third term was transformative, it would also serve as the final peak of the wavey Perpich rollercoaster. After this, it would only go downhill as Minnesotans couldn’t get over one simple thing: They were growing sick of Rudy Perpich.

The Downfall of Governor Goofy

On January 16th, 1990, Newsweek posted an article about Perpich simply titled “Minnesota Governor’s Goofy”, going over his many eccentric traits and bizarre proposals to fix the state’s problems. While many in the state may have dismissed such an article in the past as another example of desperate GOP attacks, this time it began to resonate with voters. By the time 1990 came around, most voters had disapproved of the Governor, with him reaching an all-time low of just 36%. Conservatives didn’t like him for his big spending, liberals didn’t like him for his socially conservative positions, and moderates didn’t care for his goofiness.

Obviously, this wasn’t a great spot to be in, and no one knew that better than liberal DFLers. They had long been frustrated with Perpich, and with him well on track to be defeated next November, they saw it as their chance to field a credible challenger. This time, they would go with the former commissioner of commerce and Perpich ally Mike Hatch, who had grown increasingly concerned by Perpich’s poor standing in the polls and alleged abuse of power. This time, it looked like Perpich might finally be finished. After all, he had grown tired of campaigning, Hatch seemed to reflect the modern DFL better than he did by that point, and his approval rating kept going down. Surely, this time, Perpich would lose to the party, right?

Well, Perpich would once again prove his political talent, this time by tapping into a salient trait voters still liked: his work with foreign leaders. This time, it would be his invitation to Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to visit Minnesota, which Gorbachev accepted, giving Perpich a massive boost in the polls and favorability in the convention. This successful endeavor proved to be enough to push him ahead in the primary, winning both the party endorsement and the primary election itself months later. For Perpich, it was yet another masterclass in political skill, showing that he was willing to do whatever it took to improve his political fortunes.

Meanwhile, the Republican side proved to be a bitter fight between the moderate and conservative wings of the party, this time being a fight between conservative businessman Jon Grunseth and moderate State Auditor Arne Carlson. While the two battled for months, Grunseth would eventually defeat Carlson, earning just under a majority of the vote. While he would make an effort to unite the battle as much as he could, his relatively unknown image and lack of charisma prevented him from getting the moderate wing behind him, giving Perpich the early advantage in the process.

For most of the general election, it looked like Perpich was in a good spot for re-election. While most liberal and moderate metro DFLers didn’t like him by this point, they still weren’t willing to sacrifice him to a conservative Republican like Grunseth. For his part, Perpich would use Grunseth’s lacking campaign to define him on his own terms, accusing him of being an absentee father who couldn’t be asked to pay his property taxes despite being wealthy. While Grunseth would attempt to strike back with ads including his own family members, it didn’t seem to make much of a dent in the Perpich machine, and it looked like Perpich was on track to cruise to a fourth term.

However, the race would be turned completely upside down on October 15th and 22nd, when accusations of sexual misconduct were made against Grunseth. While he would attempt to fight back against them, they were simply too damming to ignore (if you want to know the details, you can read about them here), and pressure mounted on him to step down, with Carlson even mounting a write-in effort of his own. Eventually, he would fold to this pressure, dropping out of the race on October 28th.

Technically, as a result of Grunseth stepping down, Carlson would be the default GOP nominee, as he came in second place in the primary, and state law designates that position as the next in line if the main guy drops out. But this also requires the party to approve the selection, and initially, many conservatives within the party were hesitant to act, considering Carlson’s liberal position on several different issues. But after some nudging towards Carlson from Rudy Boschwitz, the conservatives within the party decided to approve Carlson’s nomination, viewing it as the best choice to beat Perpich.

While the conservatives had made many bad calls during Perpich’s political career, this is one of the rare wins they would score. While Perpich was able to earn the reluctant support of metro liberals and moderates in the face of conservative Republicans, this was something he had a far harder time doing in the face of a metro moderate opponent, especially one that outflanked him on abortion rights, a key issue in the 1990 election. Seemingly overnight, many of the same voters who had swallowed their pride and were planning to vote for Perpich suddenly switched sides, including many top staffers on Mike Hatch’s campaign. While Perpich still had the support of his more conservative rural coalition, he couldn’t afford to bleed this much support in the metro. But as the days went on, this problem only got worse, and as Election Day came, Perpich knew that his political fortune had finally run out.

Indeed, on Election Day 1990, the result was a victory for metro voters. On one corner, they had successfully taken down conservative Republican U.S. Senator Rudy Boschwitz, replacing him with a left-liberal activist and college professor Paul Wellstone. On the other corner, they had finally taken Perpich down, with Arne Carlson winning 50.1% of the vote to Perpich’s 46.8%. This decline in support came almost entirely from the metro, which saw Perpich lose the biggest counties in the state by massive margins not seen since his 1982 primary bid. This time, the rural areas wouldn’t be enough to carry him thanks to weak numbers in Southern Minnesota.

After decades of being in power, voters had finally said to both Perpich and Boschwitz “Oh bye-bye to the Rudy’s”.

Conclusion

After this defeat, Perpich would not make a return to the political scene. While he had privately wished he could run for Governor in 1994, he also knew that his colon cancer was becoming harder and harder to beat, with it eventually consuming his life and leaving him to live out the rest of it in peace and quiet, a rarity for the active former Governor. After spending years battling with cancer, he passed away on September 21st, 1995 at the age 67, leaving behind his kids, his wife Lola, and his two brothers.

When analyzing his legacy and many achievements, I’ve found that there are a ton of lessons you can take away from it. From a political perspective, Perpich was both highly flawed and highly skilled. While he did a poor job at appealing to the different factions in a party, liberals or conservatives, he would do an excellent job at political showmanship, becoming one of the most personable politicians of the 20th century in the process and winning many friends on both sides of the aisle. From a policy perspective, his achievements are both obvious and subtle. While most people probably wouldn’t know what he did today, his interest in building, rural investment and education made Minnesota into the attractive zone for young workers that it is today, being one of the few Midwestern states not suffering from brain drain today. From a personal perspective, Perpich was a bizarre but caring person, seemingly willing to take even the weirdest choices all in pursuit of helping the state he loved.

More than anything, I think the main lesson is that you have the know where the people you are working with are. Understanding this is key to doing any kind of political work, and it can make or break whatever kind of project you are invested in. Rudy Perpich’s career shows off where this can go well and also how you can fail. When it worked, he created programs and infrastructure that still define the state today and had charisma that even allowed him to defeat long-term incumbents and propel him to presidential candidate speculation. When it failed, his political career went with it, even if he could fight off the inevitable for a few cycles.

That’s why Rudy Perpich is so interesting to me, not just because of his impact on Minnesota, but also because he is seemingly one of the very few politicians who was both bafflingly out of step on the game of politics and also a master operator fully in touch with the concerns of the North Star State. You don’t see that too often, so it’s good to take a long look at them every now and then.

Sources

“Remembering Rudy Perpich, the Governor Who Turned “Outstate” into “Greater Minnesota.”” Bemidji Pioneer, 6 Nov. 2022, www.bemidjipioneer.com/news/minnesota/remembering-rudy-perpich-the-governor-who-turned-outstate-into-greater-minnesota.

Wilson, Betty. Rudy! The People’s Governor, 2005.

“1990 Gubernatorial Race Rocked by Scandal.” MPR News, 21 Nov. 2017, www.mprnews.org/story/2017/11/21/history-1990-gubernatorial-race-rocked-by-scandal.

“Gorbachev Visit Was a Special Moment for Mpls. Family.” MPR News, 3 June 2015, www.mprnews.org/story/2015/06/03/watson.

Toure, Yemi. “Governor Goofy” Replies: Newsweek Called Him...” Los Angeles Times, 18 Jan. 1990, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-01-18-vw-133-story.html.

“Remembering the Ballad of Rudy and Bill.” MPR News, 21 Jan. 2016, www.mprnews.org/story/2016/01/21/remembering-the-ballad-of-rudy-and-bill.