Television Perception and Collective Memory

How television coverage warped our perception of the 1960s

Hey readers! This article is slightly different than the ones you are likely used to, because this piece is also doubling for my history project at college. The writing style is going to be a bit different, but given the subject matter, I think you guys might find it interesting regardless. Apologies for the delay in articles, just been super busy with school and my social life. But assuming I get things back in order, expect more pieces coming this summer!

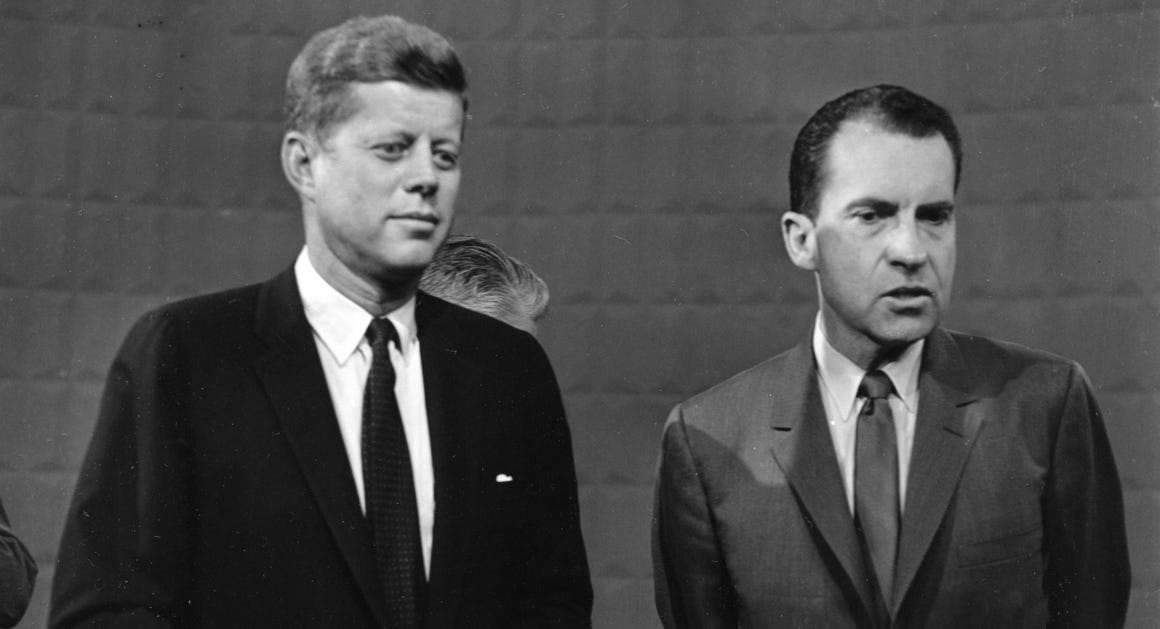

If there was one event that I believe best summarizes the 1960 presidential election, both in regards to how it is viewed then and now, it would undoubtedly be the first presidential debate held on September 26th. The first ever debates to be televised, it is often retrospectively viewed today as the moment when a young John F. Kennedy began his ascension to the White House, much to the chagrin of a tricky Richard Nixon. To the television audience, the contrast between the two men became immediately obvious the second they walked out on stage. Kennedy looked calm, resolute, and had just the right amount of glow reflecting off his skin and hair. Meanwhile, Richard Nixon looked like his face was melting under the lights, made even worse by the fact that his choice of a light gray suit blended in with his skin tone. Additionally, while Kennedy stood confident and upright, Nixon was slumping with poor posture due to a knee injury that had occurred just hours prior. Some who watched even wondered if Nixon was ill, including his mother, who reportedly called him soon after the debate concluded. From there, so long as Kennedy didn’t completely bomb, he had effectively won the debate by default. While he had often been portrayed as an inexperienced novice in comparison to his opponent, this debate had presented television viewers with the exact opposite. Kennedy looked ready to lead, while Nixon looked nervous and unsure. After this, Kennedy would establish a clear lead over Nixon in Gallup polling, a lead which he would never relinquish over the next month and a half.

However, that is only half of the story. While the debate was televised, many others listened to it on the radio instead, so factors like posture and proper makeup did not factor into the equation. Naturally, this made things far more advantageous for the Vice President, who was still capable of articulating himself properly despite his evident physical ailments. While polling data on the matter is sparse and features questionable methodology, the few bits of information we do have suggest that Nixon had been victorious among radio listeners, a stark contrast from the overwhelmingly negative reception he got from television viewers. In just the very first televised presidential debate, public consensus had become strongly divided over perception. This even ran up to the top, with running mates Lyndon Johnson and Henry Cabot Lodge both reportedly believing their ticket partner had lost. While Kennedy would receive the polling bump and the retrospective praise, further analysis of the topic makes things much more complicated than initially assumed.

Over the decade, gaps in perception, thanks to television, would only become more and more commonplace. In his book entitled The Nineties, author Chuck Klosterman argues that television in the 1990s had “become the way to understand everything, ruling from a position of one-way control that future generations would never consent to or understand” (Klosterman, 271). I believe that the same principle applies to the 1960s as well, in a way that is perhaps even more dramatic. From Vietnam to civil rights to elections themselves, television not only transformed the perceptions of these issues among Americans living in the 1960s, but also our retrospective view on the decade as well. In this piece, I want to go over some of the most iconic events of the decade and explain how television played an irreplaceable role in defining our outlook on them.

The Civil Rights Consensus That Wasn’t

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the ongoing mistreatment of African-Americans, particularly in the segregated Jim Crow South, had slowly been attracting more and more ire from American liberals and activists. While most of the older ones had previously been willing to put these grievances aside for the sake of the New Deal, this clear violation of human rights became increasingly unacceptable to younger people, especially since many of them had just fought overseas on the pretense of protecting liberty from the horrors of German and Japanese fascism. The Cold War only made segregation look more outdated and hypocritical. After all, how can America claim to be interested in spreading liberty when a sizable chunk of its population isn’t even treated as equal?

This train of thought would only continue to grow more popular, particularly as landmark civil rights victories such as Brown v. Board of Education began to crop up throughout the 1950s. By the time the 1960 election had rolled around, both major candidates had been forced to provide lip service to the civil rights movement, albeit while also staying careful about it so as not to alienate white southerners. Ultimately, this is the last election where such a balancing act would end up being necessary, as the years to follow would ultimately force the hands of politicians in both parties. On June 13, 1963, the now-President Kennedy would declare his support for civil rights unequivocally and launch an initiative for legislation on the matter. After Kennedy was assassinated later that year, the new President Lyndon Johnson would take up his old boss’s effort, using his long-time experience as a legislator to break through the Southern filibuster with northern Republican support. This ultimately became the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which officially outlawed employment discrimination and segregation in public places. Months later, after his party secured a landslide victory in the 1964 election, Johnson would sign the 1965 Voting Rights Act into law, outlawing practices previously used to prevent African-Americans down South from voting. In just twenty years, the previously unchallenged Jim Crow had come crashing down, retrospectively being viewed today as the time when America had finally begun to start living up to its promises of freedom and liberty for all.

How did such a dramatic downfall happen in such a short period? While it comes down to many different factors, television’s role in this is undeniable. To best explain this, let’s consider the context in which John F. Kennedy decided to deliver his address on civil rights. Mere hours prior, Alabama Governor George Wallace had decided to engage in a now-infamous act of political theater in which he stood in front of the Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama to prevent the enrollment of black students. While it would not devolve into a crisis that many in the Kennedy administration feared, the President still felt the time was appropriate to make an address on the matter in light of the disappointment he felt after seeing the television coverage. As explained by Robert Schlesinger in his book entitled White House Ghosts: Presidents and Their Speechwriters, the speech was written in less than two hours, with Kennedy even reportedly telling his speech writer that “For the first time, I thought I was going to have to go off the cuff” (Schlesinger, 136). Despite the rushed nature, the speech was very well received by the public, albeit alongside predictable scorn from southern whites. Many of them had been watching the same television coverage that Kennedy had been, and they were equally confused and upset by what Wallace was doing. Television coverage made the incident look like the last gasp of a reactionary and backwards society that was fundamentally at odds with the spirit of the United States.

This exact story would play out over and over again for the next year, and the civil rights movement continued to look more justified in its cause. This was one of the main topics of Aniko Bodroghkozy’s Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement, and she hits on two important elements that allowed television to work against segregationists. The first was that whenever television would cover a civil rights march, it was almost always one that was both peaceful and featured a considerable number of white people present. The famous “March on Washington” on August 28th, 1963, is the best example of this. While most of the marchers were black, the size of the crowd and the evident white presence on the television made the event appear harmonious and heroic to casual observers, making the cause of civil rights more popular in the process. As Bodroghkozy describes it, “The coverage celebrating “black and white together” in peace and harmony pointed to the solution to all the news about racial strife in Birmingham, in Cambridge, and elsewhere that preceded the march; the solution did indeed require the institution of change, but the insistent focus on black “civil rights subjects” and their respectable-looking white allies made change look not only unthreatening but positively desirable” (Bodroghkozy, 100).

This increased popularity led to the second element that helped civil rights advocates: the equal-time rule. Since networks were obligated to present two sides of an important issue with equal levels of coverage, it allowed civil rights advocates to break further into the mainstream. This was something that segregationist politicians were increasingly bitter over, such as Mississippi U.S. Congressman John Bell Williams, who said, “We know of no responsible person in Mississippi who would go on the air and speak for integration” (Bodroghkozy, 61). While some civil rights activists were also critical of this rule because it gave a platform to segregationists, it was something that would ultimately play to their benefit as coverage of segregation became increasingly negative and indefensible.

Ultimately, as television coverage became a more popular medium throughout the 1960s, it became increasingly more difficult to justify the merits of Jim Crow, including to top politicians like John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. The large, diverse crowds for civil rights posed against the anger present by politicians like George Wallace and John Bell Williams made the former side look like the inevitable future and the latter look like reactionaries desperately clinging to the past. When the 1965 Voting Rights Act was signed into law, it would have been easy to assume that the march towards progress on civil rights could only continue to look upward.

However, just five days after the bill was signed into law, those same television screens would begin to show just how clouded this perspective was.

On August 11, 1965, the Los Angeles Police Department attempted to arrest 21-year-old Marquette Frey for recently failing a sobriety test. Frey would attempt to resist this with help from his mother, Rena, and brother Ronald, which ultimately ended in a physical confrontation where Rena was struck in the face and all three were arrested. While all of this was happening, a group of onlookers began to approach the scene, and rumors sparked that the police had kicked a pregnant woman. This provoked outrage, with many in the crowd viewing it as yet another instance of mistreatment by a racist and corrupt LAPD. While attempts were made to calm the situation, it quickly devolved into a five-day-long riot, resulting in 34 deaths and millions of dollars in property damage.

This riot is the subject of the first chapter of Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland, and this is for a very important reason. Over the next few days, network television would glue its helicopter cameras to the ongoing chaos, with seemingly every possible angle being covered for the perfect amount of spectacle. It was utterly stunning to those on the top, with Lyndon Johnson questioning how such an event could have been possible, given everything that had been accomplished over the last twenty years. After the debate had supposedly been settled, a city would be caught in flames over that very same subject.

At the end of the day, this whole spectacle exposed how the television's perception of an inevitable civil rights victory was just that: a television perception. Given how poor coverage had been for the segregationists and how positive it had been for the civil rights crowd, it was easy to assume that the debate was over. But this had never been in line with the truth, and the coverage of the Watts riot put this fact on full display. There were still millions of people who had not come to terms with this supposedly ingrained consensus, and the Watts riots coverage made them impossible to ignore. As Perlstien himself puts it, “The supposed American consensus had always been clouded. The experts had just become expert at ignoring the clouds” (Perlstein, 11).

After this, fights for civil rights would never again be seen in the same light. While there were noticeable advancements for them in the latter half of the 1960s, such as the 1968 Civil Rights Act that dealt with fair housing, these wins are not generally remembered much today. Instead, the legacy of the movement is usually cut off at August 6th, with August 11th being the start of a season of riots that would become one of the most popular symbols of this tumultuous decade. By television having such a large role in the coverage of civil rights fights and the Watts riots, it made it easy for those in the past and present to overlook those who stood in the way of civil rights, as well as overlook how civil rights fights had progressed after August 6th. With no television, it is nearly impossible to imagine either of these events playing out in our collective memory as they have.

The Victory That Was Lost

If there was anything that has defined Lyndon Johnson’s presidency more than civil rights, it is undoubtedly the war in Vietnam. While he was not the first president to have been involved in the conflict, he had been the prime architect of its massive escalation following the Gulf of Tonkin incident. This was initially uniformly supported by both sides of the aisle, but it soon became obvious that the United States was stuck in a grueling quagmire, resulting in thousands of young men being killed or wounded. Despite promises of victory right around the corner at seemingly every opportunity, the Johnson administration was never able to achieve its objectives, sending the entire presidency into a doom spiral and forcing Johnson out of the 1968 presidential election.

On a base level, it’s clear that television had a large role to play in this total erosion of confidence. Footage of the war and coverage of the United States’ failures in the conflict had become common news throughout the mid to late 1960s, fully exposing the increasingly unbelievable rhetoric of final victory coming from the Johnson White House. While this by itself is a good representative of television’s influence, I still don’t believe it fully accounts for just how much it was capable of shifting public perception. For that, I think it’s important to analyze the event that likely did the most damage to Johnson’s cause: the Tet Offensive.

From a military standpoint, it’s hard to argue that this was anything but a loss for the North Vietnamese. While they had some initial success in the early days of their invasion due to catching the South Vietnamese and Americans off guard, they were soon easily repelled once forces were reorganized, inflicting heavy casualties on the Viet Cong in the process. Additionally, their goal of sparking revolution among the South Vietnamese populous went nowhere, even despite how dysfunctional the South Vietnamese government had become by this point. While the first few days were certainly shocking, the outcome of the fight was a military success for the United States.

However, the television made sure that none of that mattered. While the outcome may not have been a victory for the North Vietnamese, the show of retreat on the part of the Americans looked like nothing less than a total rebuke of the narrative that the Johnson administration had been showing. This is best detailed in George Pavlidakey’s An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of the Tet Offensive and its Effect on Public Opinion about the Vietnam War, which goes over numerous examples of images that would come to scar the American psyche, such as North Vietnamese soldiers taking over the U.S. Embassy in South Vietnam and a South Vietnamese officer executing a Viet Cong POW. It was a stunning example of just how television could alter the reality on the ground through sheer coverage alone. Pavlidakey hits directly on this point, saying, “What the U.S. media did not say explicitly, it said implicitly, especially through images. All the imagery of bombings, corpses, shootings, fires, and other destruction gave the appearance that all of Vietnam “was in flames or being battered into ruins, and all Vietnamese civilians were homeless refugees”. Even when journalists knew otherwise, they were overruled” (Pavlidakey, 48).

Today, the Vietnam War is rightfully viewed as having been a failed mission from the start, and the Tet Offensive is often regarded as an American failure. As detailed by Michael Kazin and Maurice Isserman in America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, the idea that a victory in Vietnam could have ever been achieved was delusional at best and cynical at worst. It had always been built on the fundamental misunderstanding that people would always appreciate any alternative to communism that was backed by Americans, even if said alternative was even more morally depraved. Backlash to this mission likely would have still existed without television, as the core of the operation had always been broken.

However, it’s hard to imagine that it would ever evolve to the extent that it did. The fact that the war had received such widespread coverage day in and day out helped reinforce Americans’ perceived decline in prestige. The images being contrasted so strongly with what the establishment had been telling the people only made this disconnect worse, and not even a military victory like Tet could come even close to overturning this. Not only had televisions been able to spark more outrage via increased attention to evident failure, but they had the power to have people perceive victories as failures.

The Anti-War Party (Featuring The Pro-War)

On February 27th, 1968, CBS News anchorman Walter Cronkite—often labeled the most trusted man in America—would deliver a speech that declared that the ongoing war in Vietnam had devolved into a “dire stalemate”, criticizing the Johnson administration for portraying a message of blind optimism despite the reality on the ground. These are sentiments that he had been long been harboring before this, but the crisis around Tet prompted him to speak out, declaring that “it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could”.

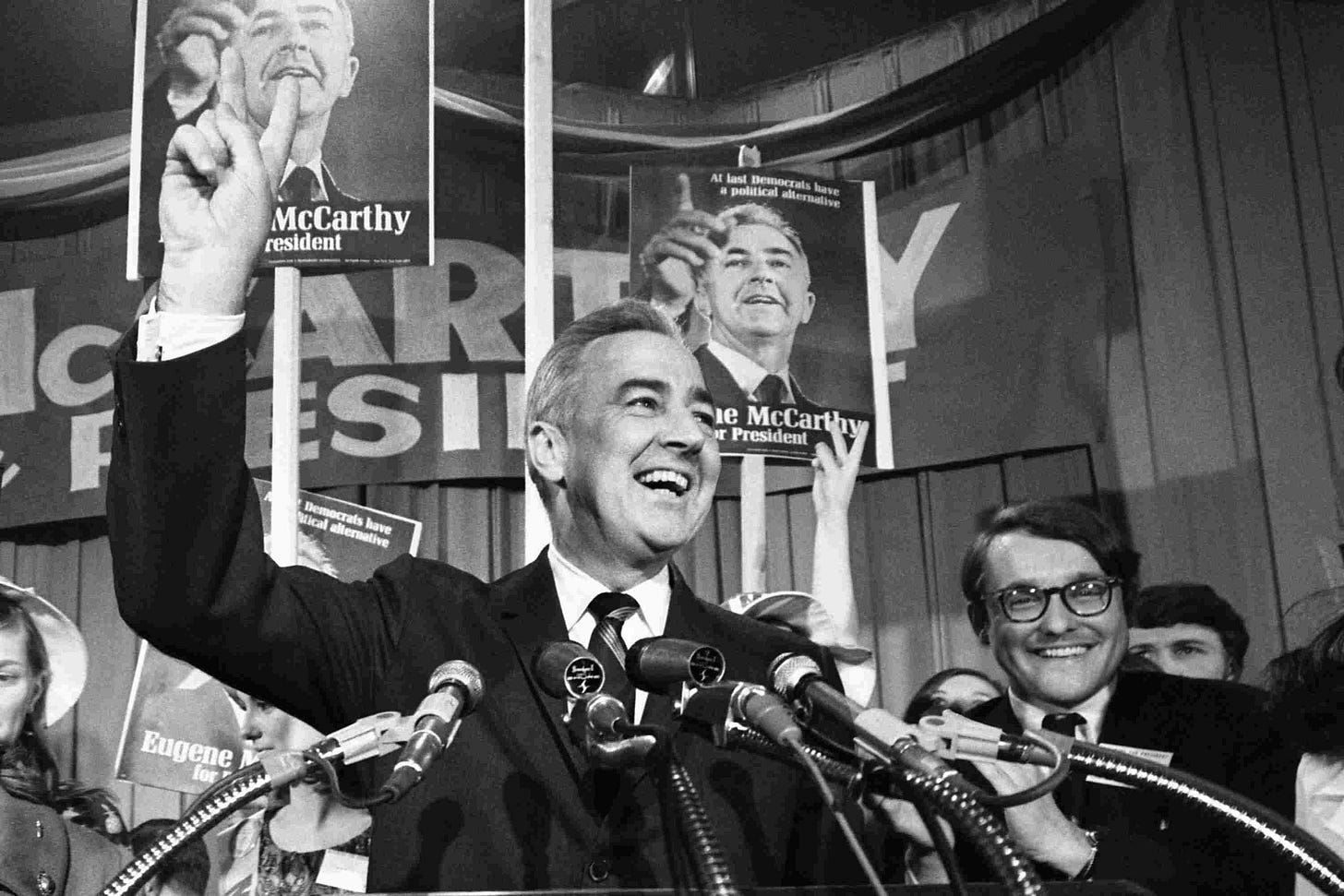

Just a few weeks later, Lyndon Johnson would suffer a crushing blow on March 12th in the New Hampshire Democratic primary by Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy. This showing by an incumbent President was remarkably weak, and television networks stopped at nothing to report it as such. Since it had happened so close to the Tet Offensive and Cronkite’s address, it was easy to assume that this was the culmination of an anti-Vietnam War movement that had been slowly building up throughout his presidency, and that their fervor had finally come back to bite Johnson in the ass. This was certainly how Johnson himself perceived it, announcing 19 days later that he was dropping out of the presidential race to negotiate peace with North Vietnam. This is also the outlook we generally view the result today, with one Politico article making note of McCarthy’s anti-Vietnam War bona fides before anything else. Based on everything surrounding it, it’s easy to assume that television’s perception of this as a vote against war was clear.

However, you may have noticed that I did not mention the actual margin in the race. That’s because, despite everything I just listed, it was a race that Lyndon Johnson had won, 49-42. The contest that had been one of the key drivers behind his decision to withdraw from the presidential race altogether had been a win. While this wasn’t a fact that was hidden from the public, this was similar to Tet in that the poor perception by television played a much bigger role than the actual result itself. Someone who was influenced by this was Lawrence O’Donnell, who details in Playing With Fire: The 1968 election and the Transformation of American Politics how he had long assumed for decades that Johnson had lost the New Hampshire primary due to just how poor the coverage had been for him in its aftermath, as well as happening to miss the more specific headlines produced by the New York Times the next morning. All of this was maddening to Johnson, or as O’Donnell put it, “This was the night that LBJ could finally see how completely upside down his world was. Everyone thought the guy who came in second ‘won’ the New Hampshire primary” (O’Donnell, 131).

Additionally, while much attention in television was and has been directed to the Vietnam War as an overriding factor in this result, the data does not point to this consensus. In a Louis Harris poll conducted days after the result, it found that had the issue of Vietnam been the only issue on the minds of primary voters, McCarthy would have only scored 22% of the primary, a loss of nearly half of his total support base. In addition, once again covered in Rick Perlstein’s Nixonland, “two polling experts, Richard Scammon and Benjamin Wattenberg, looked more closely at the data and learned that 60 percent of the McCarthy vote came from people who thought LBJ wasn’t escalating the Vietnam War fast enough” (Perlstein, 232).

Ultimately, the sentiment behind the New Hampshire primary result was much more a general opposition to the Johnson administration, and while some of that included those who believed he was escalating too much in the Vietnam War, there were also plenty of others who viewed it in the exact opposite direction. This opposition was also the minority faction, at least within the confines of the New Hampshire Democratic voting electorate. However, both of those facts ultimately got overshadowed both then and retrospectively by how the result looked on television, in addition to the context preceding it. Given how disastrous Tet had been, how increasingly widespread the anti-Vietnam War movement had grown, and how it had respected allies like Walter Cronkite speaking on their behalf, it was easy to assume that the New Hampshire primary result was just the culmination of all of that. By presenting it in this fashion, television helped warp our perception of one of the most critical election results of the 1960s.

Conclusion

When I finally finished reading Chuck Klosterman’s The Nineties, the main element that stood out to me was just how much Americans in the 1990s had experienced important cultural events through their television screens. From the Persian Gulf War to the O.J. Simpson trial, much of what came to define the culture of the 1990s in our collective memory was based on perceptions that were made from what was presented by the television media.

I had initially planned to do a project covering how much the television media networks had influenced the 1960s broadly. This is still an important aspect of what I’ve covered here, but I also realized that I desired to do more than just connect television coverage with historical events. Ultimately, I wanted to figure out how much television could shape our understanding of events we associate with the 1960s in comparison to reality. In looking at it from this angle, it’s clear that no analysis of the events of the 1960s, nor our collective memory of those events, can be understood without television. The assumption of a permanent coalition on civil rights was born from how television stations had initially portrayed both sides of the fight, and its subsequent erosion was aided by those same television stations. A military victory had images produced that were so damaging to American prestige that it was widely regarded as an unmitigated disaster. Lyndon Johnson’s victory in the New Hampshire primary was not only viewed as a career-ending defeat but a direct repudiation of his escalatory policies in the Vietnam War, all despite evidence to the contrary.

None of this is meant to criticize the media networks of the time or now, nor is it to argue that television’s influence is negative overall. Media perceptions that go against the reality on the ground were nothing new by the 1960s, and they would have continued to exist regardless of whether televisions were produced or not. Rather, I believe that this serves as an important historical research lesson to be cognizant of how media coverage, intentionally or otherwise, can shape perceptions of events to such an extent that the reality is hardly even recognizable in our collective memory. While causality and contingency are incredibly important for research, neither of them will work without also considering context.

That’s what makes the 1960s so interesting: It is perhaps the clearest example of a time defined almost entirely by pure perception, regardless of whether it was true or false.

Works Cited

Perlstein, Rick. “Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America”. Scribner, 2008. Accessed 22 Apr. 2025.

“Walter Cronkite’s Report on Vietnam - February 26, 1968” Internet Archive, 26 Feb. 1968, https://archive.org/details/CBS1968. Accessed 20 Apr. 2025.

Isserman, Maurice and Michael Kazin. “America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s”. Oxford University Press, pp. 67-82, 1999, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1wXX18KsNGjRxK1OnuW5p6EAalMZTnJDh/view. Accessed 20 Apr. 2025.

History Editors. “The Kennedy-Nixon Debates”. History, 21 Sept. 2010, https://www.history.com/articles/kennedy-nixon-debates. Accessed 25 Apr. 2025.

The Learning Network. “Sept. 26, 1960 | First Televised Presidential Debate”. The New York Times, 26. Sept 2011, https://archive.nytimes.com/learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/26/septe-26-1960-first-televised-presidential-debate/. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

NCC Staff. “How the Kennedy-Nixon debate changed the world of politics”. National Constitution Center, 26 Sept. 2017, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-debate-that-changed-the-world-of-politics. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

“Gallup Presidential Election Trial-Heat Trends, 1936-2004”. Gallup, 2008, https://web.archive.org/web/20170630070844/http://www.gallup.com/poll/110548/gallup-presidential-election-trialheat-trends-19362004.aspx#4. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

Klosterman, Chuck. “The Nineties”. Penguin Books, 8 Feb. 2022. Accessed 27 Apr. 2025.

Schlesinger, Robert. “White House Ghosts: Presidents and Their Speechwriters”. Simon & Schuster, 15 Apr. 2008. Accessed 1 May. 2025.

Bodroghkozy, Aniko. “Equal Time: Television and the Civil Rights Movement”. University of Illinois Press, 1 Aug. 2013. Accessed 2 May. 2025.

Pavlidakey, George. “An Analysis of U.S. Media Coverage of the Tet Offensive and Its Effect on Public Opinion about the Vietnam War”. New College of Florida, Apr. 2012, https://ncf.sobek.ufl.edu/NCFE004648/00001. Accessed 6 May. 2025.

Glass, Andrew. “McCarthy nearly upsets LBJ in New Hampshire primary: March 12, 1968”. Politico, 12 Mar. 2016, https://www.politico.com/story/2016/03/mccarthy-nearly-upsets-lbj-in-new-hampshire-primary-march-12-1968-220521. Accessed 8 May. 2025.

“Poll Finds Vote for McCarthy Was Anti-Johnson, Not Antiwar”. The New York Times, 18 Mar. 1968, https://www.nytimes.com/1968/03/18/archives/poll-finds-vote-for-mccarthy-was-antijohnson-not-antiwar.html. Accessed 8 May. 2025.

O’Donnell, Lawrence. “Playing With Fire: The 1968 Election and the Transformation of American Politics”. Penguin Publishing Group, 6 Nov. 2018. Accessed 8 May. 2025.