A Success Story: The Democratic-Farmer Labor Party (Part 2)

How a string of good decisions and lucky outcomes led the party to define Minnesota politics

Disclaimer

If you have not read part 1, go read that one! Otherwise, this series won’t feel complete. Or do what you want, your loss.

1946-1948: The Battle for the DFL

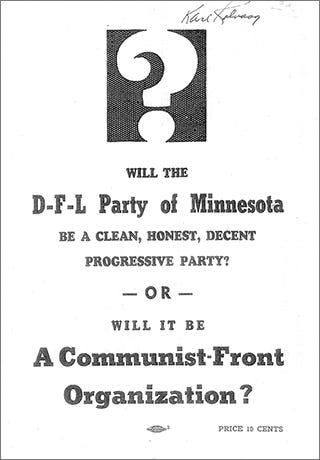

After the shocking rebuttal to him at the convention in 1946, Humphrey and his allies had a mission on their hands: purging the new DFL of those they considered to be communist sympathizers hostile to their more anti-communist views. This would initially prove to be a somewhat difficult task.

After all, the DFL was hardly tested by this point. The one statewide loss they had in the 1944 gubernatorial race wasn’t unexpected. By the time Stassen resigned in early 1943 due to a promise he’d serve in the US Navy, he was very popular, and the man who replaced him, Edward Thye, was also a moderate Republican who was generally liked for similar reasons as Stassen. It wasn’t expected that the DFL would be able to take him on yet, even if Roosevelt carried Minnesota. For those reasons, 1944 didn’t pose much importance to the future of the party, especially as they improved their margins in Minnesota on the presidential level, and made US House gains surrounding the Twin Cities area.

1946, on the other hand, would be key to how the party chose to operate in the future. Since 1944, the war that had partially brought the two sides together had ended, and the president who the Farmer-Labor worked with so closely died at his vacation home in Georgia early into his fourth term. Not to mention, for the first time since 1936, the governorship would be an open contest, with Governor Thye deciding to run for the US Senate, eventually defeating incumbent Senator and former Farmor-Labor member Henrik Shipstead in the primary. This gave the DFL the advantage of not having to fight incumbency advantage as they had before, and it left open the possibility of a DFL flip. It was all up in the air now, and since the leftist faction was more in control at this point, it was going to be the faction that would receive the blame if things went poorly.

They got the blame.

1946 was a famously terrible midterm for Democrats, as Truman was suffering from the problems that came from a post-war economic slowdown and crippling low approval ratings. Minnesota was no exception to this rule, and the DFL was about to get a shellacking. Outside of one rare bright spot in the Iron Range, the DFL lost pretty much everywhere in the state. They would lose the governorship and US Senate seat by 19 points each, and all their Twin Cities US House seat gains from 1944 would be wiped out, leaving them with almost nothing left. The national environment was just not on the side of the Democrats, and I think it’s clear that no matter who was leading the faction, the result would have likely stayed the same.

However, even though I’d argue it wasn’t fair to blame them, since the leftists were the predominant faction, they were the ones that received the blame for the DFL’s failures in 1946, and to Humphrey and his crew, it was the opening they needed to take charge. Non-Republicans in Minnesota were sick and tired of losing after eight years, and they were willing to hear Humphrey out. But how did he take control?

He started by taking shots at what he described as the “communist party lines” within the DFL, arguing that if the DFL ever wished to be a truly progressive party movement, it needed to purge them. They then began working to build a statewide affiliate of Elanor Roosevelt’s Americans For Democratic Action, a liberal and progressive organization that was also staunchly anti-communist. Finally, they would fully flex their strength at the 1948 DFL precinct caucus, where their abilities would truly be realized.

The man in charge of this final operation was Orville Freeman, a key ally and friend of Humphrey’s. Under his control, he would lead a successful effort to get volunteers out to the event, and when the day finally came, they were ready and clearly more prepared. Despite heavy resistance from the leftists, the anti-communist wing won over the leftists, and they held clear power over the DFL.

The left would not respond kindly, boycotting the convention in Brainerd that occurred two months later, holding their own in support of Progressive Party candidate for President, Henry Wallace. It wasn’t an entirely nonsignificant break-off, with the most notable person being Elmer Benson, the Farmer-Labor side of the negotiation table that created the DFL, who would later leave the party entirely. Some others joined the Republican Party, similar to how Henrik Shipstead did years prior.

However, in comparison to where they started in 1944, their numbers were just too small for it to really matter anymore. Humphrey was hailed as a hero by the anti-communist faction, and in kind, they endorsed his bid for the US Senate in 1948 enthusiastically, where he would go up against incumbent Republican Joseph Ball.

This was the turning point of the DFL, the point when they shed almost all socialistic parts and went full speed ahead with progressive liberalism. It was a party that laid out Humphrey’s vision almost to a tea, a shocking rise in the party that he only gained real prominence in just five years prior. Now, he was ready to take it to the next level.

1948: The DFL Takes the Stage

Prior to this point, Humphrey didn’t have a lot of national influence. His influence in Minnesota politics was growing rapidly, but unless he did something big, something that would influence the national party itself directly, he would end up just being another politician, even if he managed to defeat Ball in the general election. If he didn’t do anything with his influence, his legacy would ultimately come down to one thing: being the first Democratic Senator elected in Minnesota since before the Civil War. Humphrey, determined to avoid this underwhelming legacy, sought to wield his growing influence in an area not many were willing to do so.

Civil Rights.

As most of you are probably likely aware of, prior to 1948, almost no one in the Democratic Party was really willing to take the issue on. The reason for this is pretty obvious: the Democratic Party at the time relied on a racist, white supremacist coalition in the American South. Roosevelt’s presidency demonstrated this extremely well, which saw Roosevelt not only avoid pushing for any anti-lynching legislation, but also blocked African-Americans from benefitting from several of his New Deal programs, done as a compromise to appease racist southern Democrats into voting for New Deal programs. Before 1948, while many northern Democrats found the policies of the Jim Crow South abhorant, many unfortunately chose to go along with it for political benefit.

However, as the progressive base grew in the Democratic Party, so too did the demand for doing something on the issue of civil rights. Despite being a supporter of civil rights and having a commission designed to recommened how to move forward on the issue, President Truman was not going to be the one who led the effort, as he would go on to shelve that commission and the party platform contained little more than platitudes on supporting civil rights.

To Humphrey and other liberals, this was an unacceptable compromise, and with his growing influence, he would seek to make sure that minority voices were properly heard in a way they never were before in the Democratic Party. Working with fellow anti-communist liberals like Paul Douglas and John Shelley, they sought to have a vote on what they called a “minority plank”, which called for banning lynching, banning school segregation, and ending job discrimination. It was the most pro-civil rights proposal seen by far, and predictably, it was fiercly opposed by southern Democrats, and Truman’s advisers didn’t want to put it to a floor vote out of fear of losing their support.

I want to stress something here. Humphrey really didn’t have to do this. Minnesota was overwhelmingly white, and he stood little to gain electorally by persuing this issue. He was risking upsetting the party bosses and by extension, ruining his chances of making it in national politics. But to his credit, Humphrey didn’t back down. In fact, he went on to give an famous speech on the floor of the convention, where he would proclaim:

“To those who say, my friends, to those who say that we are rushing this issue of civil rights, I say to them we are 172 years late! To those who say this civil rights program is an infringement on states' rights, I say this: the time has arrived in America for the Democratic Party to get out of the shadow of states' rights and walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights!”

It was an extremely effective speech, and thanks to further efforts by him and his allies, it passed the convention, and the minority plank was officially added to the Democratic Party platform. Humphrey had made a real impact on the party, moving it forward on an issue it had been stuck on for generations. Through his actions, he made several allies and enemies, with the latter group going on to nominate South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond onto the Dixiecrat ticket for president.

Most importantly, however, through his actions, he made the DFL a relevant player in national politics, and that would pay significant dividens back home.

1948: The DFL Breaks Through

Humphrey had finally made himself and the DFL players in the national party operations. But just how was that national party doing?

When the Dixiecrats broke off, it was with the explicit purpose of destroying Humphrey and his liberal allies’ work. Mainly, make the Democrats lose the 1948 election to the Republican nominee Thomas Dewey, and by extension, get them to strip the civil rights agenda out of the platform to earn back their support. It was a pretty scary plan, both for the parties liberal base and the establishment, the latter of which was looking to secure a full term for President Truman.

And initially, it looked like they would pay big for their decision. Truman was consistently considered the favorite the lose the election in November, not just because he was behind Dewey considerably, but he was also losing votes to the Dixiecrats and Progressive Party mentioned earlier, ones he wouldn’t be able to afford losing in the event of a close contest. This was also bad news for the DFL and Humphrey, who depended on Truman winning not just for their electoral prospects in the state, but also to have influence in the national party going forward.

Fortunantely for them, they began to do better and better in the polls. Even as the media dismissed Truman and the Democrats, it became more and more clear that the environment was trending in their favor. This became true in Minnesota as well, with Humphrey becoming the clear favorite to become US Senator, and the governor's race shifting more and more into tossup territory for the first time since the 1930s. This would be the first election where the DFL would be under Humphrey’s control, and his political career, both nationally and statewide, was on the line.

And when the election day results came, it was clear to everyone watching: the DFL finally broke through.

Both Truman and Humphrey would go on to win their respective races, as many had expected. But this was not a close race. This was a blowout victory for the two men, with Truman and Humphrey each winning the state of Minnesota by 17 and 20 points respectively, on par with the margins Republicans were putting up in the state for years. Not only that, but the DFL would pick up three US House seats and keep the incumbent Republican governor within 8 points. With Truman winning nationwide, not only did the DFL prove themselves capable of winning statewide under Humphrey, but they proved themselves capable of moving the party forward while being much more liberal on civil rights matters.

Of course, the DFL could have maybe done better that night. They could have flipped more US House seats that were previously held by Farmer-Labor members. They could have flipped the governorship. They technically could have done better. But make no mistake, this election was a huge breakthrough for the party, and it solidified Humphrey’s place in it.

After 1948, it was clear that the Republicans weren’t going to be able to take statewide elections for granted anymore like they had for the last decade. The Humphrey machine was just too difficult to ignore.

1950-1952: Playing Defense

Going into 1950, the base that the DFL had built up in the 1948 elections was put into question. The popularity that Truman got from his shock victory was long gone at this point, and it looked very possible that the Republicans would once again achieve control of both legislative chambers as they did in 1946. Unlike in 1948, this would not be an opportunity to play offense. They would have to bunker down and play defense.

This was demonstrated well in the gubernatorial race, where Republican incumbent Luther Youngdahl was planning on running for a third term. Elected to a first term easily in 1946, he had a bit of a scare in 1948, having his margin reduced from 19 points to 8 points. While this wasn’t a DFL flip, it was a demonstration of how well they did, as a race for governor hadn’t gotten that close since 1934.

This year, there would be no opportunity for such an overperformance, as Youngdahl would be benefit from a strong national environment and incumbency, two tools that made it practically impossible to defeat him. With potential pickups against the US House Republicans looking seemingly impossible as well, the DFL sought to cut their losses and protect what they already had in the US House.

All things considered, when the midterms actually came, they did a good job at this. While the Democrats did poorly in the 1950 elections overall, the DFL did achieve what they set out to do. Not only did all of their US House Representatives win re-election, all of them with one exception did so by comfortable margins. The DFL had finally learned the ability to take advantage of incumbency, and it played wonders at helping them from being wiped out like they had in so many Republican midterms prior.

1952 would be the next test of this, even more so than 1950. Truman was even less popular than he was in 1950, and after twenty years of the White House being home to a Democratic president, the American people were ready for a change. The Republicans, after nominating five losers in a row, finally nailed on a big winner, that being beloved World War II general Dwight Eisenhower, who was the strong favorite throughout virtually the entire election against his Democratic opponent, including in the state of Minnesota.

This was shaping up to be a bad year for the DFL. They had been able to defend their seats in a Republican year, but this one was shaping up to be a good amount bigger, and many weren’t sure if it would hold up. Worse for them, the bad environment meant that it was unlikely they’d be able to take advantage of Governor Youngdahl’s retirement. And with incumbent Republican Senator Edward Thye running for re-election shoring up Republican support downballot, this could have ended up being a rough election for the DFL.

But it wasn’t. They pulled it off again.

Despite Dwight Eisenhower winning the state of Minnesota by 11 points, despite Republicans taking the governorship by 11 points, and despite Senator Thye being re-elected by a 14 point margin, the DFL had done it again. They protected all of their US House seats, a miraculous showing for them in the face of a Republican wave. They didn’t just pull off a defensive strategy. They mastered it.

To address the obvious, it is definitely underwhelming that the DFL wasn’t able to make any gains in 1950 and 1952. They didn’t even really get close to, whether it be in the statewide offices or US House seats. In that sense, to draw a modern parallel, its similar to the results the Democrats had in the recent 2022 midterms, a similarly underwhelming showing when shown in a vaccum.

I think its important, however, like that election, to remember that the results could have been so much worse for them, and potentially had much longer lasting damage to their standing in Minnesota. Thanks to their excellent defense of what they had, however, they were primed to make gains going forward and hold onto a strong base that would stick by them even when they were at weak points.

And that’s exactly what they would do.

Part 3 will be out soon.

Response to Feedback

I wanted to add something here at the end addressing feedback I got on my first piece, because I just wanted to express deep appreciation for those that left commentary on my last piece, it means the world to me.

Everyone that left comments were kind, and that really gives me a ton of motivation to keep persuing writing, something I only recently discovered I have a real knack for. So thank you guys for that.

As for the critiques, the most common one expressed was that these pieces are too long, and should be made a bit shorter and less drawn out. This is a fair criticism, as was something on the back of my mind as I wrote that piece and this one you are reading right now. It can be an accessability issue, one that I myself have difficulty getting over when looking at other writers, unless I really like their past work.

For now, this is something that will unfortunantely have to stay around. The history of the DFL is pretty long and complicated, and I feel like I’d be doing a disservice if I missed or cut things out I otherwise would have if the pieces were made shorter.

However, once this series is complete and I begin work on other pieces, I will make my best efforts to narrow the posts down in length, while also making sure I don’t miss crucial and important details.

I’d once again like to say that I really appericate all the feedback left on the last post, and welcome any feedback on this post, as well as anything else I write in the future. Expect more content from me in the future.