A Success Story: The Democratic-Farmer Labor Party (Part 1)

How a string of good decisions and lucky outcomes led the party to define Minnesota politics

The date is March 17th, 2023. After several days of debates and votes, the Minnesota Senate had successfully passed a measure guaranteeing free school lunches for young students, something that had already passed successfully in the Minnesota House just over a month earlier. The Democratic-Farmer Labor Party (or DFL), who headed up this project with minimal Republican votes and going up against laughably insane opposition, sought to capitalize on this moment, by them holding a large signing ceremony joined by children, teachers, and other advocates for this.

This isn’t anything new, especially not in the current legislative session they had. The DFL, who had recently gained a statewide trifecta in the 2022 midterms, sought to capitalize on this newfound political power they had been missing out on for eight years. Several big progressive priorities they had been sitting on for years were finally being passed, whether it be codifying abortion rights into law, making Minnesota a safe haven for transgender Americans, or establishing a paid-leave program in the state. The amount they were doing was absolutely incredible, especially when factoring in the fact that they held the State Senate by just a single seat that was decided by just 321 votes.

But it was March 17th, the day that all of those projects, both preceding this day and succeeding it, would truly come to the spotlight of the media and activists all across the country. The day that truly put the party into the spotlight of the country.

And a lot of it came down to this lucky shot, a picture of Governor Tim Walz being hugged and embraced by the young children that were surrounding him after he signed the bill into law.

It was one of the most heartwarming political displays in recent memory, an incredible photo op for the governor, and it did wonders at exposing the DFL to a new audience not seen in previous years. It not only invited the praises of pretty much everyone left of center and involved in Democratic politics, whether it be more establishment-leaning figures like President Barack Obama or more progressive-leaning organizations like More Perfect Union. But it also had the beneficial effect of making Republicans look absolutely terrible in comparison. By comparison, not only have they done nothing in terms of helping young students be able to learn with a full stomach, but were also in the process of making child labor laws laxer, with Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders’ photo op, in particular, drawing potent comparisons with Walz, showing just how out of depth Republicans really were when it came to the issues.

When looking at all of the legislative success of the DFL, it can be difficult to imagine where it all came from. Just last year, the thought of Minnesota being the hub of a progressive haven was extremely difficult to imagine. While the state had always leaned more blue in comparison to the rest of the country, it was not a safe bet for Democrats. While it looked likely that Governor Walz was going to see another term, it was also likely to most that it would be similar to his first term: one defined by Republican obstruction. For the first four years of his tenure, the Republicans were only in control of the State Senate, with them not holding any statewide offices and being in the minority of the State House. Despite this clear disadvantage everywhere else, they were determined to hold firm in the State Senate, blocking virtually every priority that Governor Walz wished to fulfill, with the big notable piece of legislation passing being a compromise police reform bill on July 21st, 2020, made in response to the killing of George Floyd just under two months prior. Going into 2022, it was expected that this would balance of power would stick, with both the State Senate and State House being up for grabs. Not many predicted a trifecta on either side, and it was expected that Minnesota would just be business as usual.

As we all know now though, this did not become the case. As the red wave didn’t materialize, the DFL showed off a shockingly strong result, only beaten by the likes of other incredibly strong state Democratic parties in states like Michigan and Colorado. Not only did their streak of winning every statewide office stick, not only did Governor Tim Walz and Secretary of State Steve Simon improve on Joe Biden’s margin in Minnesota despite being a redder year, not only did they hold on in the hotly contested State House and have a net loss of zero, but miraculously, despite odds stacked against them, the DFL managed to capture the State Senate, taking their trifecta they had desperately been trying to achieve for eight years.

It was an incredibly shocking result and one that was not seen coming by most. Who would have thought the DFL would secure a trifecta after losing what was thought to be their biggest chance at achieving one in 2020? But in retrospect, it fell in line with a party that is, and remains to be, one of the most effective statewide parties in the entire nation. It’s not perfect, however, and has had moments of weakness where the future of progressivism in the state looked to be put into question.

In this piece, I wanna examine how the DFL has done and continues to do, a great job as a party, while also going over its weaker times in the past.

1918-1936: The Rise of the Farmer-Labor Party

As most of you are probably likely aware, the statewide affiliate of the broader Democratic Party in Minnesota is the project of a nearly century-old collaboration effort that started in the 1940s between the Democratic Party of Minnesota and the third-party left-wing Farmer-Labor Party. This collaboration was done in response to the increasing levels of dominance put on display by the Minnesota Republicans in the state. But how did the Republicans get so dominant? Moreover, why was the Farmer-Labor so important that Democrats needed to merge with them? It’s a long story.

When the Farmer-Labor Party first came about in 1918, it did quite well at establishing itself on a federal level, securing at least one of the two US Senate seats in Minnesota through the mid to late 1920s. However, it struggled to find footing in the statewide races. Minnesota did have a strong progressive labor and farming voting base in the north and west, but it kept getting outvoted by the more dominant Republican base in the more populated south and east, with some crossover votes even coming from those north and western areas. While the party did have the effect of turning the statewide Democratic Party into a minor party, they just weren’t able to beat the Republicans, who had dominated the state ever since the time of Lincoln. For now, it just appeared that progressive politics in the state would have to wait for a time to shine.

Finally, that time to shine would come, as the Great Depression would change the political trajectory of the state forever. The strong economy that kept Republicans popular throughout the 1920s evaporated in a near instant, and they would suffer severe political consequences for this. The Farmer-Labor Party, which had been stuck in second-place hell for more than a decade, would finally have its chance in the 1930 election, the first election since the stock market crash. Even better, the incumbent Republican governor, potentially seeing the writing on the wall, sought not to run for re-election.

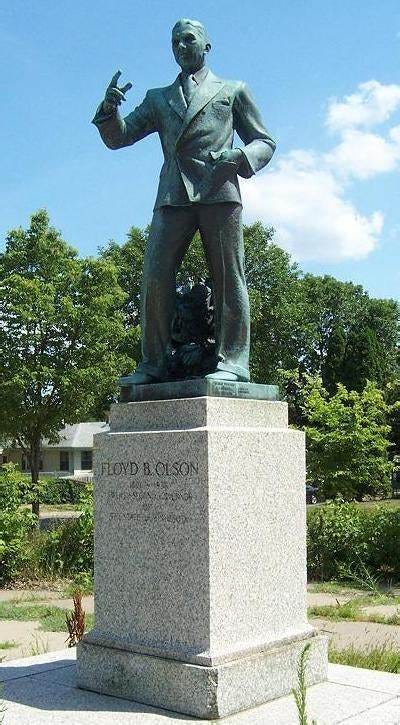

The Farmer-Labor Party would choose to nominate Floyd Olson, a county attorney for Hennepin County, home to Minneapolis, the largest city in the state. Olson had a reputation for being a strong progressive force in his office, going after the Klu Klux Klan in a very public way that earned him both a lot of condemnation and respect. Despite this, he had difficulty establishing himself statewide as well, losing the 1924 gubernatorial election and for a while, making him just another Farmer-Labor politician who failed to expand the influence of the party to the Governor’s Mansion.

However, this was all about to change, as Minnesotans were no longer satisfied with years of Republican rule, and were finally seeing the Farmer-Labor Party in a way they never did before. Not only did Floyd Olson become the governor-elect, he became so by a shockingly large margin, winning by a staggering 23 points, one of the best results for any party in the governor’s race in the 20th century.

After years of struggling, the Farmer-Labor Party finally won influence statewide, and they were ready to use it. Despite Republicans holding control of the State Legislature and blocking some of Olson’s and the Farmer-Labor Party’s more radical proposals dealing with state ownership of various industries, the Governor proved himself to be an excellent dealmaker, getting through several of his big agenda items with Republican cooperation, with the most notable one being a state income tax and relief for unemployed workers in Minnesota. In effect, the Governor was establishing his own version of the New Deal in Minnesota, albeit stripped down from his initial vision.

Speaking of which, the Farmer-Labor Party also began to grow influence in national politics under Olson as well. As Herbert Hoover grew increasingly unpopular, the Democrats were essentially guaranteed to win the White House in 1932. The only real question would be who they’d nominate. Ultimately, the party decided to go with Franklin Roosevelt, whose New Deal proposal was highly appealing to a state like Minnesota that had not voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in its entire existence. Olson immediately recognized this and sought to capitalize off of this inevitable flip. He endorsed Roosevelt in the election, and for the first time, it appeared that the Democrats and Farmer-Labor were cooperating against Republican opposition.

It worked like a charm.

Roosevelt would end up being the first Democrat to ever win the state of Minnesota, and Olson was re-elected governor right alongside him. Not only did they both win, but like in 1930, the Republicans were totally wiped out again, with Roosevelt carrying the state by 23 points and Olson winning by 18 points. This even impacted other races as well, with the Farmer-Labor Party winning a majority of US House seats for the very first time. It was a masterclass in strategy, and one that the Republicans were certainly not ready for.

After this triumph, however, the party would begin to grow more and more vulnerable. The 1934 elections showed some signs of weakness as Olson was only re-elected by 7 points, likely due to his initial unwillingness to crush a labor strike that had been occurring in Minneapolis earlier that year. Worse, before the 1936 elections, Olson would go on to die of stomach cancer, taking out the Farmer-Labor Party’s most effective lawmaker during his run for US Senate in 1936. In his place would be Elmer Benson, a US Senator who was put there by Olson himself after the death of Republican Senator Thomas Schall.

Despite losing their effective governor, the Farmer-Labor Party would once again benefit from cooperation with Roosevelt, who they would once again endorse in 1936. Roosevelt would go on to win by an even larger margin than in 1932, carrying the state by 30 points and allowing Farmer-Labor candidates to ride off his coattails, with Benson winning by 22 points, almost on par with Olson’s first run. Once again, it was a masterclass strategy by both parties and one that worked even better than in 1932. However, this would be the last cycle that the Farmer-Labor would remain relevant on their own on a state level, as they would begin to take a sharp dropoff.

1938: The Downfall

Not many people really seem to analyze the 1938 midterm elections, as covering the fact that Roosevelt opted to run for an unprecedented third term is more interesting. However, for this piece, looking at the 1938 midterms is going to be essential to understanding not just how the Farmer-Labor Party fell off, but also why it led to the creation of the modern DFL merger.

By 1938, Roosevelt’s political fortune had seemingly run out. Roosevelt’s second term would not prove to be as effective as his first, with him staking much of his political capital on Supreme Court reform done in response to them blocking several of his New Deal initiatives. This would prove to be a disaster, with conservative Democrats joining Republicans in successfully blocking the measure, as well as other New Deal initiatives that Roosevelt wished to pass. On top of this, an economic recession hit hard in 1937, raising the unemployment rate up by 5%. Roosevelt, who had previously taken credit for the increasing level of growth throughout the Great Depression, was now overseeing a backslide, and all in time for the big midterm season. Despite him seeing some New Deal priorities pass during this time, it didn’t matter. After carrying his party and his other allies to incredible levels of support for three elections in a row, the 1938 midterms were finally going to be the time when his New Deal skeptics would have a far bigger spot at the table.

This was terrible news for the Farmer-Labor Party, which had benefitted off the back of the Democratic president’s strong performances and popularity in Minnesota for years. Now that it was tanking, they really had nowhere to go but down. Elmer Benson did not have the same political talent as Olson did, and under his tenure as governor, the party would undergo significant amounts of infighting over his protection of labor strikes, done on several different occasions. While this made him popular with progressive activists, it alienated him from many others in the Farmer-Labor Party, including the Liutentiat Governor, who would stage a primary challenge against him, leaving Benson weak in the general.

Even worse, the Republicans opted to nominate Harold Strassen, a moderate Republican who many saw as a contrast between the Hoover-era Republicans and what they saw as radicals in the Farmer-Labor Party. It was an incredibly strong pick by the Republicans, and with the national environment on their side, Benson’s chances of being re-elected looked incredibly grim.

It was a disaster.

Benson, who had been elected by 22 points in 1936, wasn’t just defeated by Strassen. He was completely annihilated by him, losing by 25 points, a shockingly large number for a challenger to an incumbent. This even carried down to other results, with the Farmer-Labor being put down to just one seat in the US House, erasing all of the gains they made there in 1936. Minnesota Republicans didn’t just crack the code. They left the Farmer-Labor Party completely behind, relegating them back to where they had been in the 1920s.

The Problems with the Farmer-Labor Party

The Farmer-Labor Party would never recover from this defeat, and they grew increasingly weaker and more fringe on both a national and statewide level. Some members of the party grew more isolationist and far more alarming than that, a select few even became sympathetic to antisemitism and Nazi Germany.

Here is where I think it’s important to make something clear I haven’t done yet: the Farmer-Labor was a highly problematic party that had a lot of really terrible elements to it. Of course, it was significant in its ability to secure support for the poor and working class in Minnesota, particularly through their willingness to protect their ability to strike and collectively bargain. It had a lot of politicians who were fantastic and hold great legacies even to this day in Minnesota, particularly Floyd Olson, who I personally hold as a political inspiration. Essentially, there’s a reason they have two statues of him, one right next to the state capital and the other in Minneapolis where he built his career.

.

However, they were also deeply problematic in their social views, beyond even what many in the Roosevelt administration had. Many of their elected officials promoted anti-semitism, and it would be the main reason many of them believed in an isolationist foreign policy: they were largely fine with Nazi control in Europe because at least on that issue, it didn’t really deviate from their worldview.

This was no more evident than with their two US senators, Henrik Shipstead and Ernest Lundeen. The former was a well-known anti-semite and was known for believing several different insane anti-semitic theories, including those seen in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a well-known piece of anti-semitic literature that was taught as fact within the borders of Nazi Germany. The latter was also a known anti-semite who was even under FBI investigation for his alleged connections to Nazi spies, alleged for feeding intelligence to them several months before the US entry in World War II. Both of these men were the symbols of the Farmer-Labor Party in the US Senate, and it’s a stain on the legacy of the party that they were allowed to be there.

1940: The Nail in the Coffin

After 1938, it was difficult to imagine the Farmer-Labor’s future. Not only was their incumbent governor defeated by a margin larger than any margin they won in the elections preceding it, but they also lost virtually all of their gains from 1936. Unlike the other two major parties, who had a national presence strong enough to recover from a bad series of elections, the Farmer-Labor Party had no such luxury, being a third party pretty much exclusive to Minnesota by this point. They were in a terrible spot, but to an optimist, this may not be the worst thing ever, right? After all, going into 1940, they still held both US Senate seats, and Roosevelt’s standing significantly improved. While it may be a while for them to achieve the glory they had in the early 1930s, they were very likely to see improvements going into 1940. Right?

It was the worst year for the party yet.

Before election day had ever even come, they were already losing their representation in the federal government. Going into the US Senate primaries, frustrated with what he considered growing communist elements within the party, Shipstead would switch back to the Republican Party he left in 1920 and run in the primaries there, winning by a large margin. Worse, Lundeen would soon be killed in a plane crash on August 31st of 1940, allowing Strassen to appoint a fellow Republican to replace him. Before election day had ever even come, the Farmer-Labor Party had just lost both of their representatives in the US Senate, one of the most shocking examples of terrible political luck in recent memory.

It didn’t get any better for them on election day. Despite Roosevelt carrying the state of Minnesota by just under 4 points vs a far stronger Republican opponent, the Farmer-Labor Party completely failed to ride off of his coattails. Shipstead, who had abandoned the party earlier that year, appeared to make a good political calculation, defeating former governor Elmer Benson by 27 points, even more than Stassen’s defeat against Benson in 1938. They would perform slightly better, but still terribly against Stassen, losing to him by 15 points, an improvement over 1938, but still a significant defeat. Finally, the party would once again be relegated to one US House seat, failing to pick up a single seat from the Republicans.

They had a far more favorable environment on their side, and they still completely flopped. Even if the losses weren’t as large all around compared to 1938, it still represented a complete failure to build a coalition that they had been able to in the past, hence why I view this election as the true nail in the coffin. 1942 would just go on to prove that point even further, not really defining anything.

1944: The Birth of the DFL

After two elections of completely flopping and a third one coming on the way in the form of 1942, the Farmer-Labor Party knew something had to change. They were simply incapable of going up against the Republicans all on their own at this point. The 1942 midterms would only go on to confirm this reality, with them once again failing to oust any incumbent Republican in the state. They needed to change, and they looked to expand their work with a group that had practically fallen off entirely in the state outside of presidential politics: the Democrats.

Ever since the Farmer-Labor Party came to prominence, the Democrats were a distant third in the state, never really able to wield any kind of real influence in the state as progressive voters flocked over to the Farmer-Labor Party, even as Roosevelt turned the national Democratic Party into the home for progressives, demonstrated by Democrats consistently winning Minnesota on a presidential level after decades of almost never getting close. Their statewide base maxed out at around 15%, which wasn’t entirely insignificant in terms of votes but was in regards to their hopes of ever holding office. They often wouldn’t even run candidates, leaving it up to the Farmer-Labor Party to be the opposition to the Republicans. With the exception of the Republican parties in the Jim Crow era South, they were among the weakest state parties in the country.

However, they did have one thing going for them: a defacto collaboration with the Farmer-Labor Party through Roosevelt. One of the main things that the Farmer-Labor did in endorsing the Democratic president was kill off a significant amount of momentum for a third party to win states away from Roosevelt, which would likely just help the Republicans get back in power while losing their influence over the president. It was a smart move for both sides to work together, the Democrats would retain Minnesota’s 11 electoral votes every presidential cycle, and Farmer-Labor would dominate state politics. Some Democrats still ran statewide, but they did not compare to how well the Farmer-Labor Party did as the primary Republican opposition.

As the Farmer-Labor Party fell off however and Democratic numbers stayed the same, they decided that they needed to come together in a much stronger way. Farmer-Labor wanted to win again and the Democrats wanted to become something more than a laughing stock. On top of this, both sides wished to show a united front in the Second World War, and with both sides being broadly anti-Nazi now, they wished to show solidarity with the war effort. What they eventually decided would be something that would get rid of any potential issue with vote splitting and give both sides much more prominence in the state to fight the Republicans.

They agreed to a merger.

The men that would be most responsible for the merger consisted of the two head party chairs, Elmer Benson and Elmer Kelm for the Farmer-Labor Party and Democratic Party respectively. Make no mistake, this was a merger focused much more on necessity than agreements. While the two sides did share a large number of values with the other, there was still significant disagreement on other issues. Most notably, the Farmer-Labor side expressed less favorable opinions of anti-communist sentiment expressed by the Democrats, while the Democrats were far more openly anti-communist, on par with most of the Republicans in the state. However, this issue was put on the back burner, as the Nazis were the main foreign enemy at the time, and it was political suicide to not have this agreement in the face of Republican victories. While some Farmer-Labor members were not happy with this shift and joined the Republican Party in response, most members of both parties jumped on, and on April 15th, 1944, the merger was complete, and the DFL was born.

1944-1946: How A Mayor Came To Lead the Party

Some of you who know a lot about Minnesota history probably noticed that I left out one particularly important figure that was involved in the creation of the DFL. This was by design, as his actions leading the party through its first few years would be essential to the direction it chose to go for generations after. His impact on the merger, while big, does not compare to the impact he left on the party while it actually existed post-merger.

That man was Hubert Humphrey.

Relatively unknown at the start of the 1940s, Humphrey would quickly begin rising through the ranks of the state Democratic Party, debating the merits of Roosevelt’s 1940 campaign as a supporter of his and a member of the debate club at the University of Minnesota (Twin Cities). It was soon after this that he became involved in Minneapolis politics, with it all culminating in a run for Mayor of Minneapolis in 1943.

At face value, Humphrey should have been blown out. Not only was he running as a Democrat in a state where they were practically a third party, but he was also heavily out-funded and joined the race late, making it difficult for him to establish a broad identity. He was also going up against Republican incumbent Marvin Kline, meaning that he wouldn’t have the benefit of an open race to work with. All in all, this looks like a rough fight for Humphrey.

However, Humphrey had two big things that helped him here. The first was that Farmer-Labor did not contest this race in any significant way, meaning that he was clear to take up a significant chunk of the vote. The second and more important one was that Kline was corrupt as all hell, with the FBI office in St. Paul arguing that he was “controlled by the racketeers”. Both of these factors paid significant dividends for Humphrey’s chances and allowed the race to remain competitive despite several other odds being stacked against him. And on Election Day, that was clear to see.

Humphrey did not win. The things stacked against him were too much to overcome. However, he was able to obtain 47% of the vote, a far larger number than expected, and propelled him up the power ladder that was the Democratic Party of Minnesota. At a time when Republicans were still doing extremely well in the state, as well as a time when the Democratic Party was a distant third, seeing any result like that was something to hold up, and it instantly turned Humphrey into a key player in the merger negotiations.

Like Elmer Kelm, Humphrey was also an anti-communist, but for the sake of political expediency and support for the US war effort against the Nazis, it was put on hold and the merger went along. Humphrey now found himself as a major star in a party that wasn’t stuck in third, a significant upgrade to say the least. He would use this capital to run for Mayor of Minneapolis once again in 1945, and this time, he would easily win the election over the scandal-plagued mayor, propelling him even further than before.

While the party initially struggled to find its footing, failing to win the governorship in 1944 over the Republicans despite Roosevelt carrying the state once more, Humphrey would prove to be a bright spot for the new party to point to as an electoral success. In particular, he was a big ally to the more anti-communist members of the party, who saw him as the leader of that faction. However, this created distrust from the more leftist members, ones who after the war ended, harshly opposed the new president Harry Truman’s anti-communist focus on foreign policy. This divide, which was previously ignored in 1944 for the sake of unity, was now beginning to rear its ugly head.

This was no more evident than in 1946, when the now-mayor Humphrey was going to give a speech at the DFL convention in St. Paul, expecting a warm response. This did not occur, however, as Humphrey received a negative reception from many at the convention, which came as a shock to him after being a key player in the merger of the party two years prior. It became clear to the mayor that the leftist branch of the party was not one that he could fix all on his own. He was bitter, and the decisions he made after this in response to the convention would define the party going forward and are one of the most important moments in the history of the DFL.

Part 2 will be out soon.