A Profile In Success: Amy Klobuchar (Part 2)

How a Hennepin County Attorney managed to appeal to all corners of Minnesota

After an incredibly hard-fought campaign that saw her defeat all prior expectations, Amy Klobuchar had finally proven that her strength was not just limited to fights on popular issues where it was easy to get bipartisan support. She had proven that she could be a strong politician in actual elections as well, even in tough environments with strong opposition.

For those analyzing state politics at the time, it truly was a sight to behold to see this young lawyer become such a powerhouse overnight. For the DFL, it showed promise for a future politician who had the capability of holding office for as long as she wanted with little to no Republican resistance. For the Republicans, it was a terrifying prospect, one that had the potential to lock them out of holding power in a very important office for potentially decades. No matter which way you looked at it, the 38-year-old Amy Klobuchar was clearly expected to be going places.

However, immediately after she had won her first election campaign, a new element came into effect for Amy Klobuchar. It was one that would impact any future run she may have made in the future going forward after this. One that could make or break any future aspirations she or the DFL may have in her political career.

Her job performance.

Her victory in 1998 meant that for the first time, Amy Klobuchar was now put in a significant place of power within the government. This job was not going to be one where slacking could be overlooked for lack of interest or constituency. She would be the chief prosecutor for the largest county in Minnesota, overseeing not just one of the largest cities in the entire Midwest, but also the rapidly growing suburbs surrounding it. Since she was now in a position of influence, almost anything that went wrong over her tenure, particularly related to crime, would be pinned on her.

It was a tall order and it put her in a spotlight lit by the entire state. Thus, seeing how she did in office is crucial to understanding her future. If she was good at her job, it would make her potential electoral future that much more inevitable. If she failed, it could doom a rising star into being nothing more than a once hyped has-been, who when push came to shove, really didn’t know what she was doing in government.

So, how did she do?

1999-2006: Building Up Experience At The Right Time

If you have heard anything about Amy Klobuchar’s tenure as Hennepin County Attorney in recent years, most of it tends to be a critical reanalysis of her tenure in that position.

Between the period when she left her position in 2007, to when she was running for president in 2020, a lot had changed in regard to how the public viewed law enforcement and its relationship to race. White people, many of them previously unaware of the mistrust many minority groups had of law enforcement, began to discover that reality as movements like Black Lives Matter began to crop up in response to various instances of black people being unjustly killed by police officers. These events, along with various other factors, changed how many looked at law enforcement policies that were previously assumed to be standard.

Amy Klobuchar, herself a prosecutor, and someone who ran as a tough-on-crime politician in 1998, would soon be put under this same level of scrutiny as she was seeking to become president years later. Fortunately for her critics, there was certainly stuff to go after, much of it laid out in the Star Tribune article I linked two paragraphs above.

The most notable example brought up when criticizing her tenure as County Attorney was her highly flawed prosecution of Myon Burrell in 2002, which an AP report in 2020 showed had several inconsistencies. But there were also several instances of police shootings that occurred under her tenure, such as the 2001 killing of Efrain Pompa De Paz, the 2002 killing of Christoper Burns that sparked protests outside of her office, or the 2006 shooting of Dominic Felder, just to name a few.

For the record, I think criticism of her handling of these cases under her tenure is correct and perfectly valid, something that even Amy Klobuchar herself would admit in regard to the first case.

The principal problem in all of these cases was that Amy Klobuchar did not take it incumbent to take charging officers into her own hands. Rather, as most other county attorneys did at the time, she would leave it up to grand jurors to decide if they wanted to go forward with charges against police officers. This would create a system that was far too favorable to police in cases of misconduct, often allowing them to get off with little more than a slap on the wrist.

One could defend her on the grounds that she herself was absent from those cases, meaning that her true feelings in each case are impossible to determine. That is technically true, you couldn’t have known exactly what Amy Klobuchar thought in these cases. It’s very possible that if she was in charge of the prosecutions, they might have ended up differently.

But even still, that hardly leaves her clear of the blame, considering that she could have, at any time, taken charge of the situation, and made her opinion known on these issues. But she didn’t. It symbolized a lack of leadership and initiative on her part, something that is essential to have if you wish to be in any position of power. She didn’t have it in these moments, and it leaves a stain on her legacy as a public servant in the state of Minnesota.

So, with those concerning issues surrounding her tenure, why didn’t it stop her career in its tracks? Why didn’t these have a bigger impact on her electoral chances when she ran for statewide office?

Well, as I’ve said earlier, most of these criticisms of her tenure as County Attorney are relatively new. That isn’t to say there weren’t any critics, but most of it was hardly ever known to most who lived in Hennepin County or Minnesota for very long. Most of it came down to localized protests outside of her office that got little more than some local media interest for a few minutes, which almost always resulted in those watching the news that day forgetting about it entirely. It wasn’t the kind of controversy that really sparked serious questions about her ability as a political force.

This was for one key reason, that being that focusing on issues of police brutality was not something that received anywhere near as much attention as it does now. Her tenure was during, and just coming off of, the 1990s, which saw a wave of politicians tripping over themselves in an effort to show voters how much they were willing to stomp down on crime amid a rising percentage of it occurring during the decade. This was a local, state, and national issue, with various different policies being implemented left and right that were supposed to address this issue.

We know now in retrospect that a lot of them would be massive failures, only serving to disproportionally harm minority groups even further while not addressing anything in regard to why the crimes were actually occurring in the first place. But at the time, people were looking for anything that made themselves feel safer, and conversations about systemic inequality were pushed to the sidelines, especially since the internet was nowhere near as robust at spreading information as it is now. In essence, Amy Klobuchar’s failings in some of these cases were overlooked as a consequence of good timing. Had her tenure as County Attorney started in the 2010s or 2020s, it likely would have resulted in far more scrutiny than it otherwise would have. But she ran in the 1990s and 2000s, so her failings in the role wouldn’t be highlighted that much.

While there is certainly much to criticize, I also don’t want to paint it as though her tenure was nothing more than a failed product of its time. She did have some real success in her role, and those successes were part of the reason why she remained a star in Minnesota and the DFL itself. While she would refrain from taking action in police misconduct cases, she would be far more liberal in her role in other cases, taking action against various different kinds of criminals that no one would realistically defend, something that played very well into her image as a competent attorney to bipartisan audiences. This would also come alongside a decrease in overall crime in the city, which while difficult to give Amy Klobuchar full credit for, certainly didn’t hurt her in the face of voters either.

All of this support would culminate in her receiving an “Attorney of the Year” award from the Minnesota Lawyer in 2001. While this wasn’t that big of a deal on its own, it did reflect the high favorability that Amy Klobuchar had established in her role as County Attorney. All of the factors I listed above allowed her to become one of the most popular officeholders in the entire state of Minnesota. Not only was her image with DFL voters just as strong as ever, but her intact bipartisan image gave her a special appeal with independents and moderate Republicans. This appeal would go far beyond the better-than-expected numbers she’d pull in 1998. It was a kind of appeal that actually allowed her to win over some of these ruby-red suburbs in a way that no DFL candidate had done in decades. In her capacity as County Attorney, Amy Klobuchar had seemingly been able to crack the code, and going forward, she would never look back.

2004-2006: Amy Goes Statewide

After her undeniable political success in the role of County Attorney, it was only a matter of time before she would take the plunge into statewide politics. As her tenure went on, this inevitability only seemed to be confirmed more and more, with the Republicans not even bothering to front a candidate against her in 2002, leaving her uncontested in a year when other DFL candidates were struggling to win the county by more than a single point.

After winning re-election in 2002, she would spend the rest of her second term building up good fortune within her party for an eventual statewide bid. She would do this by volunteering as a surrogate for John Kerry’s 2004 campaign operation in Minnesota. This was an important job to hold, as Minnesota was going to be hotly contested in the 2004 election. After coming within less than 2 and a half points of winning the state in 2000, the Bush campaign saw an opportunity to pick off a blue wall state and make Kerry’s chances of winning the presidency that much harder, and also serve as a potential fallback option if their efforts in other swing states failed. Realistically, this was a state that the Kerry campaign needed to win if they had any hope of winning the White House. Fortunately, the DFL and Amy Klobuchar recognized this early on, and while Kerry would ultimately lose to Bush in the national election, Minnesota would vote for Kerry by around 3 and a half points, a shift towards the left while most other states moved to the right. This was a solid achievement by Amy Klobuchar, and it would give her credibility in regard to her ability to run a statewide campaign.

After this success, she had two more years left in her second term, which happened to line up perfectly with the upcoming 2006 midterms. When looking at the offices she could take a run at, on top of the increasing likelihood of this election being a blue wave, it was obvious that this year would be a great chance for her to make a run at statewide politics. The only question remaining would be what statewide office she’d run for.

Initially, she wanted to run for Attorney General, which was going to be left open after the incumbent Mike Hatch announced his intention to run for governor. This did make some amount of sense, a promotion from a county prosecutor to a statewide prosecutor is pretty straightforward. Combined with it also being an open race, she would almost certainly be favored to win in the general election.

However, there were also clear problems with this approach, most of them relating to the DFL primary. It had been known for a while that Mike Hatch, a longtime statewide office runner, was going to want to take on the incumbent Republican governor Tim Pawlenty. This resulted in a flux of DFL candidates also preparing to run for the Attorney General seat. These ranged from Mike Hatch’s deputy Lori Swanson, DFL House Minority Leader Matt Entenza, DFL State Senator Steve Kelley, and former U.S. House Representative Bill Luther. All of these were highly credible candidates within the party and were essentially guaranteed to give Klobuchar a significant run for her money. While her history thus far has indicated her smashing electoral success against Republicans, she had yet to ever deal with a tough primary field. While it’s very possible she would have been able to pull it off, it was also a big risk. If it had failed, it could have been a serious political setback, one that she may not have been able to recover from.

She would soon come to this realization thanks to some advice from her mentor Walter Mondale, and she would bow out of this contest. But if she wasn’t going to run for Attorney General, where else could she go?

While she could take a run at the Governor, Secretary of State, or Auditor races, these carried the same problem of highly credible DFL primary challenges, but to an even larger extent. The gubernatorial race would obviously be out of the question, as Mike Hatch was already basically picked to be the nominee for the party far ahead of time. The other two contests, while not quite as bad from a primary standpoint, still had highly credible DFL nominees gearing up to run, meaning that Klobuchar would still have significant difficulty creating a lane for herself in those races too.

This situation began to look pretty bleak. At first, it looked like Klobuchar had only two paths forward for her future career. The first path was simply just waiting it out for a potentially better time to run and stick to her job as County Attorney in the meantime. The second was ignoring Mondale’s advice and going all in on the Attorney General contest, a risky play to say the least. Neither of these was particularly appetizing and had the potential to flame out any potential interest in a statewide Klobuchar run. For an aspiring politician, this really isn’t a great spot to be in.

However, you’ve probably noticed that I haven’t brought up one particular statewide race. That race is the U.S. Senate seat, the only statewide race in 2006 that was originally supposed to be contested by a DFL incumbent. I waited to mention this one because initially, it wasn’t even close to being anywhere on the table for a statewide Klobuchar bid. While the incumbent Mark Dayton wasn’t particularly popular, to say the least, he was also only in his first term and still liked enough among the ranks of the DFL that virtually no one within the party would ever consider primarying him. If he had chosen to run for a second term, like most expected him to, he was a lock to win the primary.

Shockingly, however, none of this would come to pass. Dayton, doubtful of his own ability to win re-election in light of his controversies and lackluster funds, announced in February of 2005 that he was not going to be running for re-election. While none of them would ever admit it, this was great news for the DFL, who no longer had to be saddled with dealing with bailing out a controversial incumbent.

But it was even better news for Amy Klobuchar, who now had a very clear lane to run statewide. The most credible candidates in the DFL ranks had already been planning to run for the other statewide offices, allowing Klobuchar to occupy the DFL primary as the only truly credible candidate running. And with her only other potentially tough challenges opting out of the contest, it looked like Amy Klobuchar had finally established her statewide lane.

As expected, she would easily win the primary, earning the official DFL endorsement, and defeating her closest opponent by just under 85 points. Just like in her 1998 run, she had easily stepped up to the DFL plate. But unlike that run, this one was not going to be anywhere near as difficult. This time, virtually everything was going in Klobuchar’s favor in this election.

On top of retaining all of her green flags from 1998, it was also a far more favorable environment for her to run in. In comparison to the anti-establishment, anti-DFL environment she was running in 1998, 2006 was expected to be a solid blue wave for the party, thanks to the increasing unpopularity of President Bush over his poor handling of Hurricane Katrina and complete failure in Iraq. The latter issue, which was once said to be one of the things that put Republicans over the top in 2004, suddenly became a massive liability to them. It was an undeniable disaster, and it not only tanked Bush’s previously consistently positive approval rating, but it also made Republicans who voted for the war (aka, virtually all of them) look absolutely terrible. At best, Republicans looked incompetent and complacent after over a decade of congressional rule, meaning that their losing would be something of a wake-up call. At worst, they had outright lied about the reasons why we went into Iraq, making it so their defeat was nothing less than a moral imperative. Either way, you look at it, a blue wave was essentially inevitable once this became the popular view of Bush and his party.

This on its own would be enough to put Amy Klobuchar over the top. It’s a blue-leaning state in a heavily blue year in an open seat. That should be enough to make her the favorite by default, and given her political strength already, there really wasn’t anyone the Republicans could realistically nominate that could beat her. But just in case Republicans thought they were making it too hard for her, they would make her victory that much more inevitable on primary day.

With Amy Klobuchar running in this contest and knowing her history of massive success at the ballot box, not many Republicans were all that keen on having their high-value candidates take her on. The two most notable examples of this, former U.S. Senator Rod Grams and U.S. Representative Gil Gutknecht, were both discouraged by the Minnesota GOP to run in the Senate contest, instead relegating them to run for U.S. House seats. With their most high-quality candidates basically forced out of the contest by the party, it basically ensured that GOP primary voters were going to get nothing better than pure mediocrity for their Senate nominee. And no candidate represents mediocrity better than the actual nominee himself, U.S. Representative Mark Kennedy.

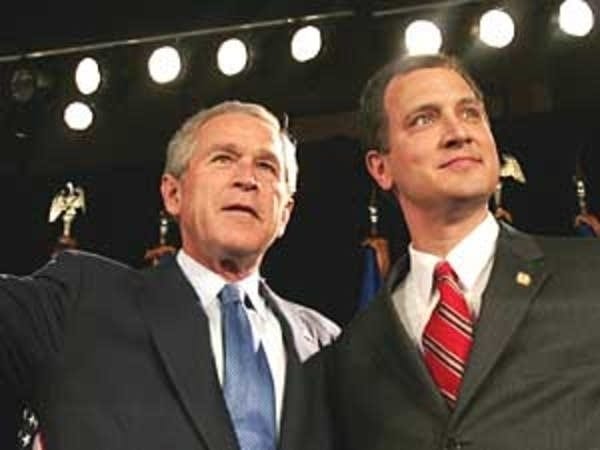

Aside from his last name (no relation), there is literally nothing remarkable, interesting, or impressive about this Watertown-based representative. During his six years in the U.S. House, he served as nothing more than a down-the-line party vote, going right along with whatever Republican leadership told him to. This played quite well for him during the high points of Bush’s presidency, so much so that he would plaster photos of himself with the president all over his congressional website. While it was certainly risky in the event of Bush’s star fading, it did make a lot of sense when you consider something else: his electoral record.

Unlike many other Minnesota congressmen like Jim Ramstad or Collin Peterson, Mark Kennedy did not possess some unique appeal in his district that allowed him to overperform expectations. In fact, he would actually do quite a bit worse than other Republicans in his district, making him a frequent target of attack by the DFL every time he was on the ballot. Nowhere was this more evident than in his final U.S. House bid in 2004, just two years prior to his Senate run. Despite Bush winning the district by 15 points, Kennedy would only win by 8 points over his DFL opponent. Despite heavily attaching himself to the president, he would still manage to lose thousands of voters in his district who voted for Bush on the same ballot.

Obviously, this doesn’t project a lot of promise. Even in a pro-GOP environment where Bush still had a solid approval rating, Kennedy would completely fail at establishing even an average performance of his own. His electoral record was undeniably weak and even worse, they were all occurring in neutral or good years for the GOP. If he couldn’t pull off a good performance in those circumstances, it was clear that he was very likely to falter completely in a blue-wave environment like 2006. This was made even worse by the fact that this blue wave was caused by the man he sucked up to for six years becoming electoral poison, meaning that he was now saddled with the image of being nothing more than a pro-Bush sycophant. Simply put, all of the things that made Bush unpopular made Kennedy unpopular as well.

If you’re Amy Klobuchar, you couldn’t have asked for a better contest if you tried. Running in an open seat in a blue-leaning state is one thing. Running in a blue wave year is another. But running against a pro-Bush underperforming backbencher? It was absolutely perfect. You really could not have asked for an easier election.

Realistically, after the Republicans went with Kennedy, she really didn’t have to do anything at all. She probably could have sat in her basement for the entire campaign season, and still come out victorious by a solid margin. That’s how bad it looked for Republicans in this contest. For all intents and purposes, Amy Klobuchar was Senator-elect months before the actual election day.

But if there’s one important thing you should know about Amy Klobuchar’s campaigns thus far, it’s the fact that she takes absolutely nothing for granted. Even in her uncontested 2002 re-election campaign, she would still go all in, putting up thousands of yard signs and participating in tons of political parades. If she put in that much effort in a race where she literally couldn’t lose, there was practically no chance that she would punt on a statewide bid, no matter how much the scale was tilted in her favor. And when push came to shove, she would go all in on her 2006 Senate campaign, just as she had always done up to this point.

But how exactly would she campaign? How would this moderate-appealing Democrat run successfully in a year where the people were demanding strong opposition to Republican rule in Washington?

If she wanted to, she could have taken the role as a partisan Democrat firebrand, running on strong opposition to Bush and his very clear failings, while also pointing to her own credibility on those issues. Klobuchar, an opponent of the Iraq War from the start, would be in a strong position to run a campaign like this, especially against a partisan Republican like Kennedy.

But there was a problem with this approach, that being that it was risking hurting her established image as a bipartisan moderate. For a long time, Klobuchar had been able to attain special appeal among suburban Republicans that virtually no other DFL candidate had in Minnesota. If she were to run as a partisan Democrat, it would certainly be successful. But it may also hurt her unique appeal with thousands of Bush voters in the state, which could come back to bite her in a less favorable year. Simply put, it wasn’t the most ideal approach if you wished to have appeal beyond the party base.

That problem is where the other potential path came in: she could go all in on that image. Similar to her advocacy for hospital stay time reform, she could run a campaign that emphasized her work on popular issues and concerns of voters. This would be a combination of having an anti-corruption message on national issues, while also emphasizing her work on addressing the concerns of her constituents on a local level as County Attorney. This path was far more likely to win over the support of more voters in her state, and would likely keep her image intact.

However, it ran into the same problem that her 1998 strategy had: alienation of the more progressive DFL base. Most people on the party’s left were not all that interested in seeing Democrats emphasize their work with Republicans. After six years of defacto Republican trifecta rule in Washington, Democrats were gearing up to finally stop Bush and his agenda right in its tracks. There wasn’t a lot of demand for a consensus candidate like Klobuchar. While she would still easily win their votes in the face of Kennedy, it could potentially harm her ability to have national ambitions, something that would almost certainly enter her mind upon becoming a U.S. Senator. So, from a career perspective, going this route would also be somewhat of a risk.

Ultimately, when push came to shove, the latter approach was the one she would take. She would run a campaign that was heavily localized, focusing almost entirely on issues that pertained to Minnesota, and Minnesota alone. When she did bring up Washington itself, she would only do so to mention her other popular stances, like opposition to subsidies for big oil companies, and the need for campaign finance reform. When analyzing her 2006 campaign, this is evident everywhere you look.

The first place were the ads her campaign ran. Almost all of them would emphasize her role as County Attorney, always making sure to frame her work in the most bipartisan, least objectionable way possible. Nowhere is this more evident than her first ad known as “My Job”, where she would mention her work to put a Democratic judge found stealing the funds of a mentally disabled woman behind bars. This would be used as proof that despite shared party affiliation, she would not play favorites when it came to protecting Minnesotans and listening to their concerns. Every ad after this would follow this same formula. One ad focused on her work to put away threatening criminals as a prosecutor while also touting endorsements from Minnesota police. Another focused on her work to get extended hospital stay time all the way back in 1995, emphasizing her ability to get real change passed in the State Assembly. Ads like this played extremely well, only giving further credibility to her image as a consensus moderate who knew how to get things done.

The second place she would show off her campaign strategy was how she dealt with her opponent. Realistically, if she wanted to, she didn’t have to engage Kennedy much at all. His many downfalls as a candidate largely spoke for themselves, and debating him wouldn’t really change the dynamics of the race. But in order to come off as available to her constituents, Klobuchar would debate Kennedy. But she wouldn’t just do it once. She would do it a staggering eight times, far more than she ever needed to, even in debates including Independence candidate Robert Fitzgerald. While it was almost certainly unnecessary, it did play well for her. Even if she wouldn’t do all that amazing in the debates, it gave people the impression that she was open and accessible, something that was going to be essential if she was going to run a local issues-based campaign. It also didn’t hurt that she kept tying Kennedy to Bush in these debates, just to bring the point home further. Once again, a very smart play by the Klobuchar campaign.

The final place this would be emphasized would be the various locations she would visit throughout her campaign. While Amy Klobuchar had cemented her credibility among voters in the cities and suburbs of the Twin Cities, she had yet to run a campaign up to this point where she would have to make an appeal to Greater Minnesota voters. Some of these places would be easy to appeal to, such as the solidly Democratic Iron Range where she already had family roots. Others would be more difficult however, such as traditionally Republican exurbs outside of Hennepin County, many of which were places that Kennedy had represented for six years up to that point. If she was going to win big, she would have to make an effort in these places as well. So, what did she do?

Well, just like her 1998 campaign for Hennepin County Attorney, she would go into the lion’s den. Throughout the campaign season, she would travel throughout the entire state, making an effort to visit as many counties as possible. Rural places would be where Amy Klobuchar would stray away from her suburban roots, instead attaching herself to her grandfather’s history as an iron miner in the rural north. Many of these places she would visit had not seen any political candidate, much less a statewide candidate, come to their turf in decades. This gave it a sense of novelty, and once again, it played into her image that she was looking out for all Minnesotans above all else. As for the traditionally Republican exurbs, she would run heavily on her track record as a prosecutor and appeal directly to their local concerns, which played over very well for the same reasons that it did with Hennepin County suburban Republicans in 1998. Both of these efforts would prove to be very successful. For the first time in decades, it looked like a DFL candidate was finally going to be competitive in deeply Republican exurbs, while also managing to hold onto and bring in a whole new base of rural voters into her coalition that had not voted DFL since the days of Rudy Perpich.

All of these factors combined created a race that was hardly ever even close to competitive. While other DFL candidates were stuck in horserace contests, Klobuchar would consistently lead Kennedy by massive margins in virtually every poll, and as the campaign went on, these leads would only continue to grow larger and larger. In August, she was up by 8. In September, she was up by 10. In October, she was up by 17. By the beginning of November, and just a few days before election day, she was leading by 22 points. The race was all but over, with Republicans basically giving up on Kennedy as early as September, where they would invest their funds into protecting other vulnerable GOP incumbents.

And as the results of election day finally came, their decision to give up on Kennedy was completely vindicated.

Overall, 2006 was a good year for the DFL. While losing the gubernatorial race was disappointing, they would do quite well in virtually every other contest that year. Not only did they maintain all of their previously held statewide offices, but they also managed to flip the Secretary of State office, the State House, and Minnesota’s 1st congressional district. While there was definitely a better result possible, the result was certainly a positive development for the party.

In terms of who was the star of the DFL that night, however, there was absolutely no contest. While other DFL candidates would win by an average of 6.8 points overall, Klobuchar would win in a landslide, defeating Kennedy by over 20 points.

The extent of her victory was incredibly shocking. She excelled practically everywhere in the state. Whether it be the cities, the suburbs, or the rurals, she would put numbers in these places not seen since a “Humphrey” or “Perpich” was on the ballot. Of the 79 counties she had won, 47 of them would be counties that also voted for Tim Pawlenty, the Republican governor on the same ballot. Even in counties like Carver, an ancestrally Republican exurban county where Pawlenty got 63% of the vote, Klobuchar would come within 6 points of winning the county, the closest any Democrat had come to winning the county in decades.

This incredibly strong showing gave separate messages to both parties. For the DFL, it was a dream come true. They had found themselves a politician who could keep the Republicans completely out of power in an important office for as long as she wanted to run. For the Minnesota GOP, it was a total disaster. Her strong result meant that unless they ran an absolutely perfect candidate in the perfect year, the chance they’d be able to defeat her was minuscule at best. Either way, the message was clear: Amy Klobuchar was not going anywhere.

Now, the 46-year-old Senator-elect had a new objective that she needed to achieve. Up to this point, she has been able to prove her worth as an incredibly effective campaigner, and also a strong prosecutor when she wanted to be. But for the first time in a decade, she would be involved in the process of passing legislation. The last time she was involved in such a process, she was acting as a frustrated outsider, often using media spectacle to get politicians on her side. This time, however, she was entering the belly of the beast, and it would be her job to build connections within the U.S. Senate if she wished to be an effective politician.

When looking back on the period of time when her first term took place (2007-2013), this was going to be a more difficult task than she probably expected. This period of time would be most notable with the election of Barack Obama, a rising star who had assisted her on the Senate campaign trail. His election would spark a new era of partisan division, with Republicans dead set on stopping anything he wanted to do the second he entered office. Republicans would be fired up for the first time in years, spawning the rise of the Tea Party movement formed in opposition to Obama’s signature legislative priorities: the 2009 Stimulus package and the Affordable Care Act. Both of these would become massive political liabilities for the Democrats going into the 2010 midterms, which would see Democrats of all ideological stripes wiped out all across the country.

Amy Klobuchar’s strong appeal going forward suddenly looked to be in doubt. In a time of growing polarization, and in a position where she would have to take votes on highly controversial issues, would she really be able to maintain her image? Would she really be able to go all through her first term keeping up support with Republicans who were growing increasingly anxious to get her party’s president out of office? It certainly seemed like a very difficult task.

But as we have already learned in this piece, she doesn’t take anything for granted, regardless of how good or bad the situation looks at first. When it looked impossible for her to lose in 2002 and 2006, she still gave it her all and came out of it stronger than ever. When it looked impossible for her to win in 1998, once again, she gave it her all and came out in a brand new position of influence. This new battle of maintaining her brand was going to be very tough, tougher than it had ever been before. But it was one that Klobuchar, now a U.S. Senator, was ready to fight against.